Ultimately, all animals carry an enigma which makes them mythological in human eyes. When Oedipus sees the Sphinx, a fabulous beast with the attributes of different animals, he listens to the question she asks him and makes that question his destiny. The confrontation between these two voices, so full of their own difference, has echoed to us through time. Like a disembodied strain of music, the part we can only hear inside our uneasy imagination.

Sometimes, animals offer the closeness of a friendship expressed with the clear words of their eyes. With animals, it is not unusual to find that we are better than we are with men and women. But on other occasions, with animals, human cruelty bears the added infamy of being unleashed on the misunderstood or the defenceless.

From their beginnings on a planet without humans, animals have now arrived in the age of mankind. They come alone in elegant singularity or in the strength of vast numbers, inhabiting a multitude of collective nouns. They advance in packs, bands, shoals, herds, flocks, schools, swarms, troops, caravans and colonies. These marching bands were cinema before the invention of film.

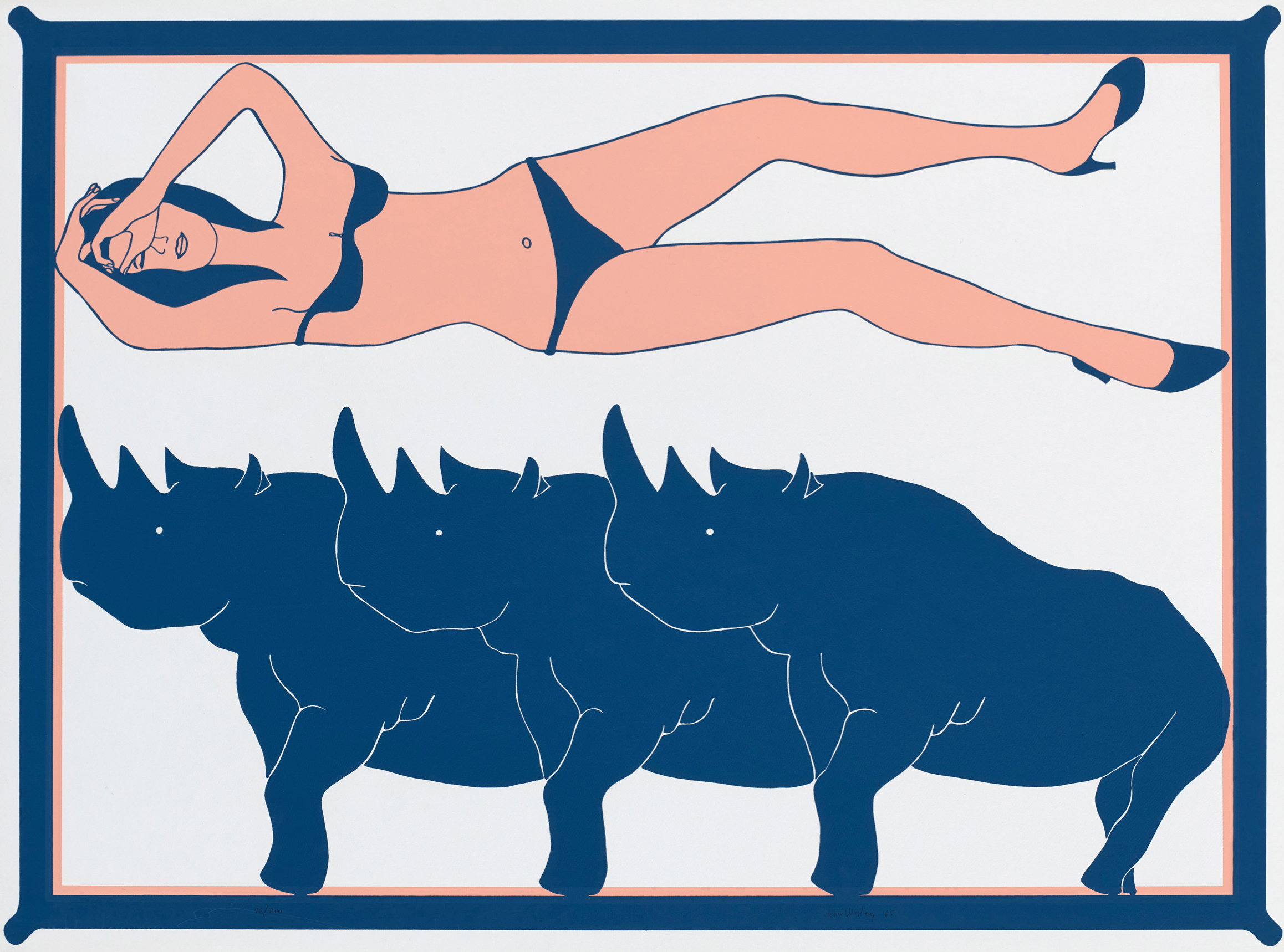

The ages of the Earth are marked by the animals that appear and then vanish as if with the magic of the glaciers. Human culture abounds in animals, as symbols, proxies, allegories and fables. From the wild beasts of Gilgamesh to Spielberg’s dinosaurs and sharks; from the lion of St. Mark and St. Jerome to Ernst Jünger’s butterflies; from the Birds of Aristophanes to those of Hitchcock and Olivier Messiaen; from the goats and deer of Lascaux to the dogs and horses of Velázquez; from the bulls and tigers of Pomar (and also Borges) to the pigs, rabbits, ostriches and dog-women of Paula Rego; from the sheep in Brokeback Mountain to the ape in Tarzan; from the cockerels of Joana Vasconcelos to Miguel Branco’s antelopes; from the wolf of St. Francis of Assisi and Prokofiev to Flaubert’s parrot; from Dürer’s rhinoceros to the lions of Delacroix; from Orwell’s pigs to Walt Disney’s mice; from the serpent in the stories of Adam and Eve and Bergman to Edgar Allan Poe’s raven; from Kobayashi Issa’s cranes to the flogged horse that made Nietzsche faint and to Kafka’s insectomorph; from the cats of Eliot, Doris Lessing, Patricia Highsmith, Vieira da Silva and Cesariny to Yourcenar’s bestiary; from Schubert’s trout to the swans of Tchaikovsky and Saint-Saëns; from Murnau’s Nosferatu to David Lynch’s Elephant Man – the worlds we have created in art and literature to gaze on our own faces and our myths, secrets, crimes and dreams are inhabited by animals. And you can hear them chirp, neigh, roar, growl, bellow, croak, squawk, quack, whistle, bray, howl and cry.

Animals are found in the genealogies of the gods and the cosmos, in biology and zoology, in narratives and representations, in words and images, in sounds and meanings, and in the shadows and the light. They are found on the peaks and in the abyss, in the heavens and in the underworld, in the air and in the seas, in the soil and in the subsoil, in caves and in houses, in temples and in tombs, on altars and in cribs, in Noah’s arks and in zoos, in aviaries and in slaughterhouses, on flags and on coats of arms.

At the start of a text to which she gave a title drawn from Ecclesiastes – ‘Who knows the spirit of the animal, whether it goes downward to the earth?’ – Marguerite Yourcenar recalls: ‘One of the tales in the Thousand and One Nights tells us that the Earth and the animals trembled on the day that God created Man. The full power of this remarkable poetic vision is clear to us, who know far better than the Arab storyteller of the Middle Ages how right the Earth and the beasts were to tremble.’

One of the key books of the twentieth century – Tristes Tropiques, by Claude Lévi-Strauss – concludes its journey with the ‘wink of an eye, heavy with patience, serenity, and mutual forgiveness, that sometimes, through an involuntary understanding, one can exchange with a cat’.

In one of the poems he wrote in his own voice, Fernando Pessoa offers an ontology of the paradoxical privileges of the animal condition over the human condition:

Share article