It seems that only time should be evoked in the presence of the work of Lourdes Castro. Nonetheless, we tend to forget the inexorability of such time (of its passage) in our appreciation of the artist’s oeuvre. We imagine that, rather than being something that passes, this time is actually an unchangeable reality. In other words, we suppose that time in Lourdes Castro’s works does not manifest itself as a flow but rather as a block and that it did not really exist in the course of the production process. The creation of these works seems to have been instantaneous. We are led to believe that they are immune to the time spent on them and the revelation of the time within them. In other words, we are made to think that they are situated outside the time that they incorporate (design time, working time, their time of existence, and their observation time).

Every work by Lourdes Castro faces us with this paradox, almost regardless of the period to which it belongs. Why does work that deals with light and shadow, work that can even be regarded as executed just with shadows and light, two realities of total spatial and temporal contingency, lead us into this erroneous appreciation? This exhibition is another opportunity for us to confirm the oxymoron of a time that does not pass.

Each image looks like a popup, as if appearing out of nowhere, hanging suspended (not only in space but also in time) on the wall and lying behind the glass as if it has fallen there (like a leaf from a tree) blown to the right place by the wind. It is not so much a state of the spontaneous generation of work but rather of the collection and display of a pre-existing reality (as if there were a cultural naturalness in things and a real absence of authorship in what Lourdes Castro presents to us). This applies to the boxes where she collects objects belonging to the same family or of the same colour, which are united by the common energy of a concentrated space and sense (or non-sense?); it applies to the flattened silver paper wrappings of children’s chocolate; it applies to the projected shadows of her friends, her everyday objects, and flowers that she has seen or picked; it even applies to the words of the poems where she selects things – items drawn, embroidered on sheets, cut out in Plexiglas, of which we see the right side, the other side, the shadow, the silhouette, the transparency, the origin and the future in a single image… Each of these images is like a beam of light at the start of its trajectory or an insect trapped in amber, paralysed in the continuum of a cinematic time to which it belongs but from whose flow it is excluded.

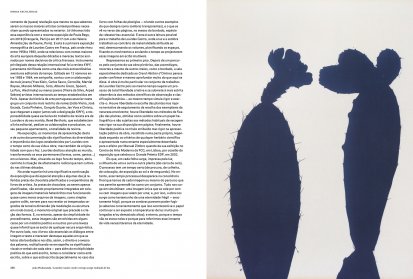

Each image is a testimony to an extreme intensity of both observation and penetration, as if we are at the core of the object and body in a geometric demonstration of the fixed human gesture and of floral nature revealed. At the same time, it is a testimony to extreme modesty and prudent distance, as things and people become transparent, stripped like flowers, analysed to the last detail, and laid out in layers like cell samples, like skins and petals peeled off and put back, though set out for us to see. In spite or perhaps because of this, no intimacy of the bodies is exposed, only their reflections. And there is here no eroticism (of the look or touch that, drawing the contours of the bodies, follows them and gives them back to us). Lourdes Castro’s images of light aspire to the pure revelation of bodies out of time (even though they are shown in action; even though this action is laid on the sheets of a bed; even though they are bodies and objects vitalised by the diversity of plastic colours). The artist captures the shadow but, unlike the demon that torments Peter Schlemihl, the hero of von Chamisso’s novella of the same name, Lourdes saves these shadows’ absent bodies for the eternity of art.

The exhibition is at Musée regional d’art contemporain Occitanie / Pyrénées-Méditerranée, in Sérignan, under the auspices of independent French curator Anne Bonnin, who has been devoting special attention to the careers of several Portuguese artists (such as Francisco Tropa and João Queiroz). It has received considerable support from the Paris delegation of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (FCG), in a test of the new scheme for sponsoring foreign events that are important to the dissemination of Portuguese culture in France. The catalogue and fringe events (talks and guided tours), however, only include the curator’s text, and none commissioned from curators at the Gulbenkian Museum or other Portuguese specialists. Although the museum is not located in a large city, it enjoys considerable prestige. This meant that the exhibition immediately received coverage in such important publications as Le Quotidian de l’Art, Libération and L’Oeil, where it was greeted with amazement and enthusiasm.

Anne Bonnin’s tour is essentially linear and mainly chronological. This is understandable in the context of the (almost) revelatory presentation that even people that we know to be our greatest contemporary artists require when exhibited abroad. We had already had this experience with Paula Rego’s recent exhibition in 2018 (Orangerie, Paris) and with Helena Almeida in 2017 (Jeu de Paume, Paris). This is Lourdes Castro’s first solo exhibition in France, where she lived from 1958 to 1983. It was in France that she rubbed shoulders with the biggest names in European art at the time and was the subject of articles written by key French art critics. A particularly important vehicle in this international relationship was KWY magazine, which has been deservedly mythologised as one of the most extraordinary publishing adventures of its time. Twelve numbers were published, using silk-screen printing, between 1958 and 1964. Younger contributors included Yves Klein, Carlos Saura, Corneille, Martial Raysse, Manolo Millares, Soto, Alberto Greco, Spoerri, Le Parc and Alechinsky, while older Paris-based international artists like Vieira da Silva and Arpad Szènes also featured. Although the history of Portuguese art brought together in this group a select set of names (João Vieira, José Escada, Costa Pinheiro, Gonçalo Duarte, Jan Voss and Christo, who exhibited under the name KWY), Lourdes and her husband, René Bertholo, were almost entirely responsible for the work on the magazine. They wrote the editorials, commissioned contributions and produced the whole magazine in their small flat.

The presentation of this and other documentation at the exhibition is not only representative of the diversity and importance of the bonds created by Lourdes with the right time in her life and work but also of the originality with which she has done it. Lourdes has paid attention to the world and turned its details (shapes, colours, gestures…) into universes. But she places them outside time and paves the way for the situation of radical withdrawal that she has cultivated in recent decades.

The exhibition continues extensively on the upper floor, where special attention is paid to the flattened chocolate wrappers and the artist’s book experiments. The chocolate wrappers are just flattened and not actually part of eclectic collages. They serve almost as mere archives of images, simple papiers collés. They reveal to us the unexpected secrets of the third dimension (of modelling or ronde-bosse sculpture), the original moment immediately before the creation of forms. And, in spite of the simplicity of the procedure, in some cases these images are shrouded in poetic mystery and in others by an almost childish levity that excludes them from any archival dryness. On the other hand, in ‘books’ we must have dialogues between image and writing. Those in which the letters are embroidered warrant attention, because they give us the right and the reverse sides of the words, multiplying the visual and verbal meanings of each work in mirrors. In addition to the poetic multiplicity of what is written, we have to consider how it is written, where it is written (especially in books with Plexiglas pages, creating other examples of what are called transparent shadows) and what we see overleaf, on the other side of the embroidery, a kind of essential ‘un-writing’. This is another possible interpretation of Lourdes Castro’s work, where light and shadow work against the materiality of the real, disembodying volumes, designing spaces, fixing movements and annulling time by projecting these images onto unchanging screens.

Let’s go back to the lower floor. After we have toured her collection of pictures, assemblages, cut-outs and, indeed, other media such as embroidery, the room devoted to the Grand Hérbier d’Ombres seems to confirm or even deepen what we have said here. The work is unique in Lourdes Castro’s oeuvre. At the same time, it not only suggests total creative freedom but is also subject to the strictest scrutiny of scientific botanical examination and classification methods. At the same time, it both simulates and stimulates accuracy. There was freedom of choice in selecting the plants but precision in the attempt to exhaust the collection of specimens from the natural surroundings. There was freedom in the methods used to attach the plants, which sit undried as a shadow on heliographic paper, but precision in the way that they were laid out on the pages. Finally, there was poetic licence in the title but precision in the public presentation of the work. They were stored in their own binder, labelled with the accuracy of any scientific herbarium and presented on a stand that was custom-made by Manuel Zimbro during his exhibition at the FCG Modern Art Centre in Lisbon celebrating the EDP Grand Prize in 2002.

And so, we find on each sheet, printed by light, in silhouette, one and another and another of around a hundred plants. Each part of the process takes place at a given time (the search, collection, fixing, exposure to sunlight and protection). Nonetheless, this time in the process disappears in the final awareness that we have of each image, or even of the path we take to be able to perceive them as a whole. We see everything at once: a single image that is worth a hundred, or a hundred images that make up one. This is why the work serves as a testimony to a fragile eternity – fragile, precisely, because the shadows seem able to escape (and we know perfectly well that this will happen if the paper continues to be exposed to light and heat for too long). It is also eternal, because time does not run off them and because we will need eternity to recount this moment in life.

*Translated by Wendy Graça

Share article