Flaubert’s undertaking was an inspiring predecessor for us. His statement on stupidity was the key with which we opened the revolving door of the ‘subject’ in the second issue of Electra. But it is also a hidden leitmotiv in all editions of this magazine, which looks on from a distance and listens closely to this time that we call our own, or contemporary, with a joy that is not always completely warranted.

This is how every edition of the magazine consistently ends with a Dictionary of Received Ideas. So far, it has included entries such as ‘reality’, ‘imagination’, ‘sharing’, ‘transparency’ and ‘concept’.

This dictionary records, interprets and spies on the words that proliferate around us, saturate public spaces and besiege private spheres, as if they were as inevitable as the floor that we cover with our footsteps or the sky that covers us with its clouds.

These words do not seem to be owned by anyone and no-one seems to be aware of or responsible for them. They circulate, contaminate (this is also one of the words) and are proposed and imposed like everything that wants to dominate, anaesthetise, stupefy and normalise.

Anyone who has read it will never forget what Roland Barthes said in his inaugural lecture at Collège de France, to everyone’s dismay and surprise. ‘Language (la langue) as a performance of all language (langage) is neither reactionary nor progressive. It is purely and simply fascist, because fascism does not consist of preventing from saying but rather of forcing to say.’

In this Electra Dictionary of Received Ideas, we seek to denaturalise and denature the naturalness and nature of these worn, glorified words. They attract like magnets and blind like headlights.

George Steiner said, ‘Good reading begins with a lexicon. We linger there and always come back to it. […] a word’s history is the raw material of its use.’ But he also warned, ‘Clichés are truths grown tired. But they can be woken, and have in them the unnerving force of the insights from which they arose. They are animate with the potential of recurrence.’

It is hard work turning these words, which float around like spectres in an empty theatre, into etymology, genealogy or ideology. And it is almost always a work of mourning. But this is the only way that they reveal what they are hiding. This is the only way for them to tell us how they abuse the naivety of everyone who uses them and to say that they ignore, forget and are unaware of all of this.

We know that this operation has its risks and dangers. The word-police are often just as or even more dangerous than the word-thieves. But this does not mean that the operation is not necessary. If we are aware of these risks and dangers, this acts as protection and an antidote against them.

Every concept (an entry added by Yves Michaud in Electra 5) and every word that says it are heard, examined and considered by someone who is forewarned and therefore knows how to use shrewd irony, critical distance and wise perspective to avoid missing the target and appropriating what is not theirs.

In this sixth issue, the old saw or buzzword in the dictionary is ‘challenge’. These days, everything is a challenge, challenging or challenged. A job, joblessness, an academic qualification, a love, a hate, a workout at the gym, home improvements, a new baby, the death of a parent, a target or a deadline are all challenges that challenge people who love to be challenged.

And even when we are talking about something that really is a challenge and is felt and experienced as such by someone who wants to overcome it, the repetition of the word ad nauseam robs it of all meaning and substance. Language is not literal, contrary to what many may think.

The writer Gonçalo M. Tavares took on our challenge (yes, yes, we’re actually saying it!) to write about ‘challenge’ in this edition’s Dictionary of Fixed Ideas. He has set out his thoughts on this idea-word in two versions that not only defend each other but also defend themselves from each other.

As his vast and well-received oeuvre shows, Gonçalo M. Tavares is highly trained and has a special talent for sniffing out suits and higher- and lower-scoring cards: verbal aces, kings, queens and jacks in every language game.

Purely by chance, but one of those objective chances prized by surrealists, many years ago Gonçalo M. Tavares wrote a chronicle about Robert Walser in a newspaper that no longer exists. The Swiss-born writer said, ‘I am alarmed by the idea of being successful in life.’ Paradoxically, his life and work have the mysterious aura of something that never runs out. His books say things that had to be said and only he could say them. His is an oeuvre that is completely cliché free.

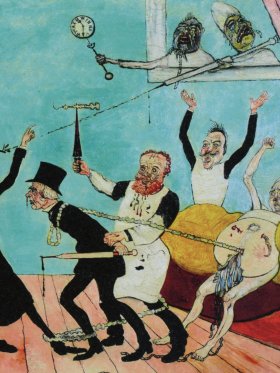

In his chronicle, which is as old as his love for the writer, Gonçalo M. Tavares speaks about a novel that Walser wrote in Berlin in 1909. Its title is the name of a young man called Jakob von Gunten. Jakob writes a diary, while at school he is taught ‘patience and obedience, two qualities with little or no promise’.

In this book, its author’s favourite, Jakob’s wealthy older brother Johann boasts a cynical shrewdness that gives the character strength over weakness.

Jakob describes his school. ‘We don’t learn much here. There is a shortage of teachers and we boys at the Benjamenta Institute will never be anyone in our future lives. We will just be small and inferior.’ But when Jakob spends time with his brother’s friends he pretends to be ‘a man with an annual income of at least 20,000 marks’. This almost ontological classification teaches us that humans are the children of the money they have.

This is why there is one piece of fraternal advice from his elder brother that sums up all the others. ‘Try to get lots of money as quickly as possible. Everything else is rotten, but so far not money.’ It is worth repeating this ending as if it were the refrain of a poem. ‘Everything else is rotten, but so far not money.’

In its ironically and prudently radical eloquence, this advice could be an epigraph of the subject in this issue of Electra. It is devoted to money, which is not a cliché, even though it is the father of many clichés.

God and devil of the world, this life and the soul, like Jehovah in the Bible, money says, ‘I am who I am.’ An angel that would be God, the messenger that wants to be the message and the means that wants to be the end, money is the devil that offers everything in exchange for becoming more and greater than he is. ‘The devil showed Him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. And he said to Him, “All these things I will give You if You will fall down and worship me.”’

As everything is becoming a commodity and being materialised, in the philosophical sense, money is being dematerialised, in the physical sense, and turning into a memory of itself. What is the sad plastic of a credit or debit card if not the memory of a sparkling, jingling gold coin?

Anyone who has read Edmund de Waal’s book The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance knows that the biography of objects and the biography of people can be found in two memories that work together in the fight against the Alzheimer’s of time and the terrible usury of its effects. In this fascinating book, the miniature animals from Japanese sash toggles, called netsuke, grow huge and take on the size of small words written in Walser’s minuscule writing.

An artist who writes, de Waal makes memory – and the works that are the memory of that memory – the heart of the darkness and light of his creation and of his aesthetic and existential thinking.

Edmund de Waal’s most recent two part exhibition, psalm, opened in the Venice Ghetto and the Ateneo Veneto to coincide with the Biennale Arte 2019. The portfolio with which he has honoured Electra asks us to look at his images and listen to his words. Both endow our times with a future memory.

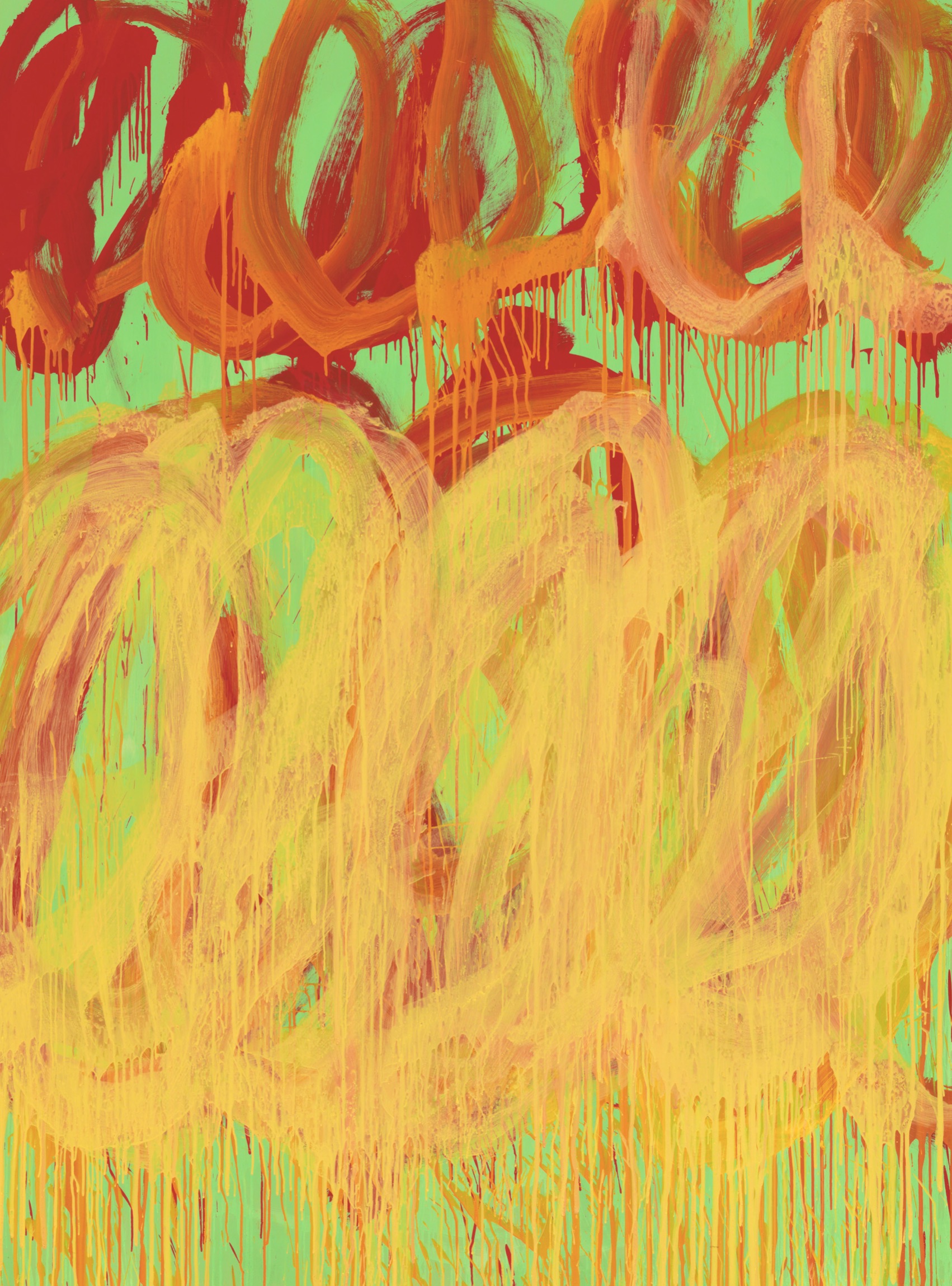

The architect Álvaro Siza is also a great builder of future memories. In his work, the river of time pushes the stone of space towards a horizon that opens and widens before our eyes. In the travel diary he has prepared for Electra, the drawings he endlessly produces create Paper Landscapes. Siza sees the world as a project, so he imagines, draws, records, predicts and transforms it. This edition of our magazine explores a variety of themes and images that steer themselves towards a point to which time draws near in order that we may hear it.

*Translated by Wendy Graça

Share article