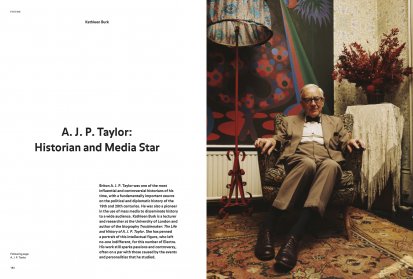

A.J.P. Taylor did not share the propensity of some to equate profundity with impenetrability. For him, the premium was, as in classical English prose, clarity. Indeed, in Great Britain, there is often the suspicion that if an author does not make his or her ideas and explanations clear, it is because even the author has not really understood them. Taylor was famous for his use of words. He was also famous for his huge range of knowledge, and the combination of the two, when added to his ability to think quickly in an original and arresting way, made him one of a kind.

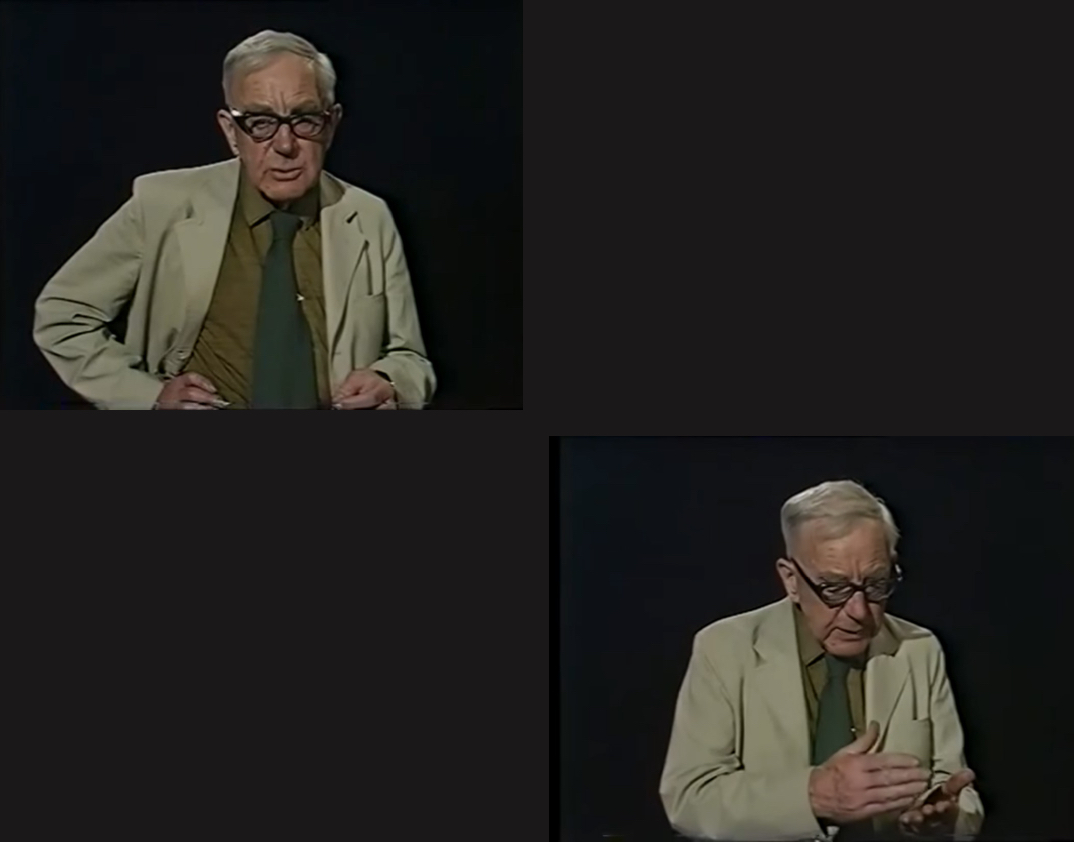

During his prime, A. J. P. Taylor was the most famous diplomatic historian in the world. Abroad, it was the books, of which by the end there were twenty-three. At home in the United Kingdom, it was the books, but it was also the journalism and the broadcasting. He was the first person ever to give lectures on television; in English parlance, he was the first ‘tellydon’ (he was a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, and in Oxford the academic staff were always referred to as dons). In short, he was both an academic and a media star, the first such combination in the UK and probably in any other country.

Taylor was born in the county of Lancashire in the North of England. The northern counties combine great natural beauty – the Lake District, the Peak District – with commercial and industrial centres which can be grimy and depressing. Northerners often take pride in their bluntness of speech and in their differences with the South: for example, they see themselves as friendlier and with a stronger sense of community. Taylor shared this sense of not conforming, in particular in dissenting against the political mainstream. He grew up in a family family with plenty of money, but with a father who was a left-wing socialist and a mother who was a devoted communist. Taylor always saw himself as left-wing, although he reserved to himself the right to determine just what that meant. Another supposed Northern trait which he shared was the pleasure in making and having money – he once said that his favourite time of year was the first week of April, when he dealt with his tax affairs. Indeed, by the time he had been an academic historian for twenty years, his income from his book-reviewing, journalism and broadcasting was higher than his salary. This disparity continued to grow.

He needed this money because, along with his liking for fast cars and good wine, he accumulated three wives, two mistresses who later became wives, six children and two stepsons. His personal life was sometimes tumultuous. His first wife Margaret, with whom he was never entirely to break the links forged in their early years together, and with whom he shared four children, tended to fall in love with other men, firstly with Robert Kee, one of Taylor’s own students, and secondly and more importantly with the poet Dylan Thomas, who used her to extract money and mocked her. Taylor took a mistress, Eve Crosland, whose brother Tony Crosland later became a senior minister in the 1974-79 Labour government. She eventually told him that either he divorced his wife, from whom he had been separated for some time, and they married, or she would leave him. He did both, but the marriage, which produced another two children, was not a long-term success. The same thing happened again. Whilst still married to Eve, he began a relationship with an Hungarian historian, Éva Haraszti, and after some years, she told him that either he divorced Eve and they married, or she would leave him. He did both. From this marriage he acquired two Hungarian stepsons. Taylor seldom liked to take decisions in his personal life and tended to drift until circumstances forced him to do so. In all of this, he remained devoted to his children. Undeniably, however, the bulk of his attention was elsewhere, on history and his career.

The fundamental reason for his importance, and the foundation on which the other parts of his career were built, was the books. Although they totalled twenty-three, a number of these were books which were normally illustrated and designed to appeal to those general readers who liked reading history. Amongst these were The First World War: An Illustrated History and the excellent The Second World War: An Illustrated History. Others were books of essays, which were largely made up of long book reviews, pièces d’occasion (which provided the historical context for an historical anniversary such as the Crimean War or a person such as Napoleon III), and his television lectures. They were very popular with the general public and with students.

Share article