‘Moscow’… How much this sound Evokes in every Russian’s heart! A. S. Pushkin

This beautiful and original evocation of Moscow, written for Electra, recalls different eras, political and cultural figures, memorable events and places of worship. The writer’s personal history intersects with that of the city and of a world that played out its destiny there. And it also talks of Eusébio and Port wine. The author, Yuri Slezkine, is a renowned historian and translator, born in Russia, who has taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and at Oxford. He is considered to be one of the world's leading experts on Russian history and has a book on the subject regarded as a work of reference.

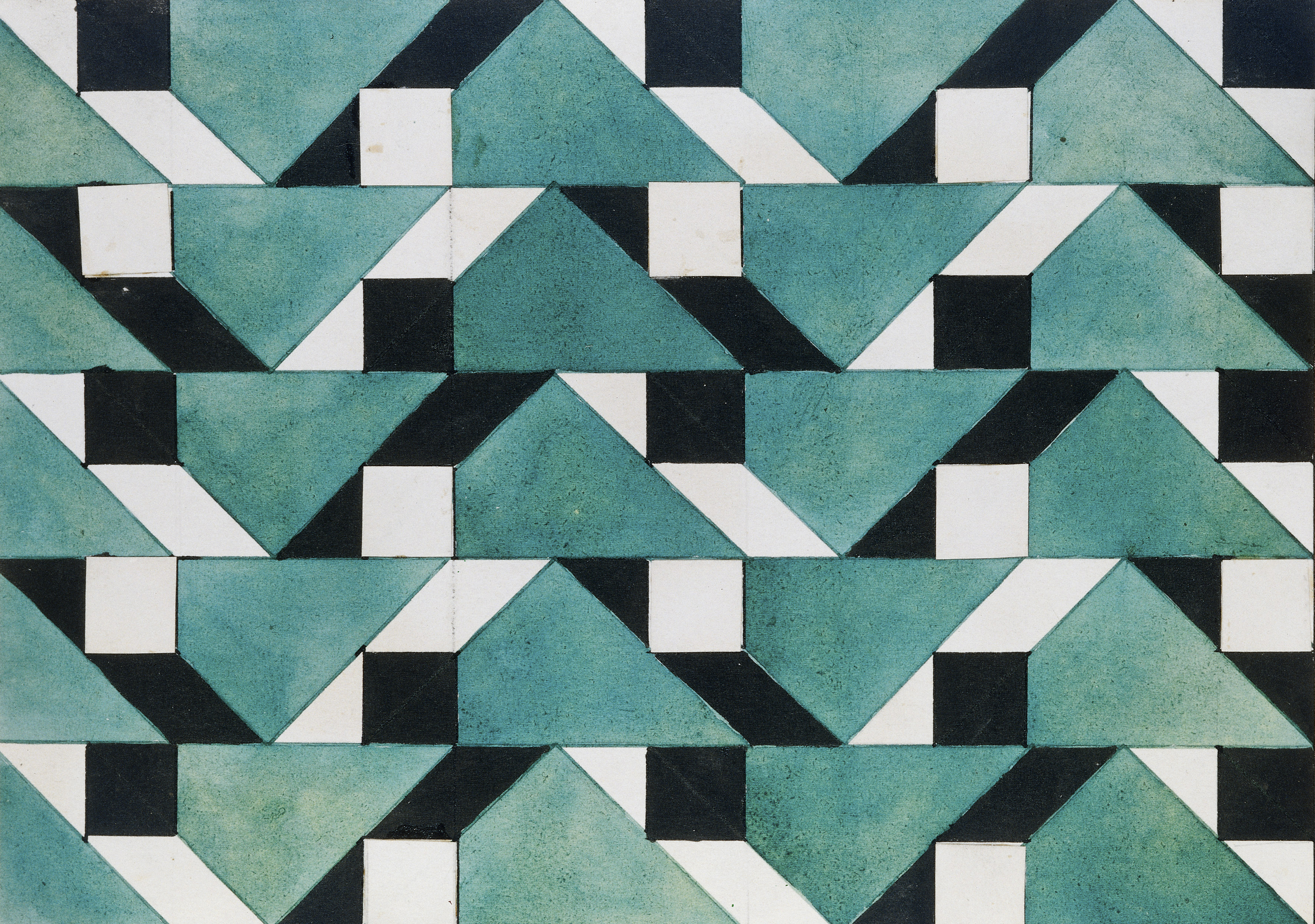

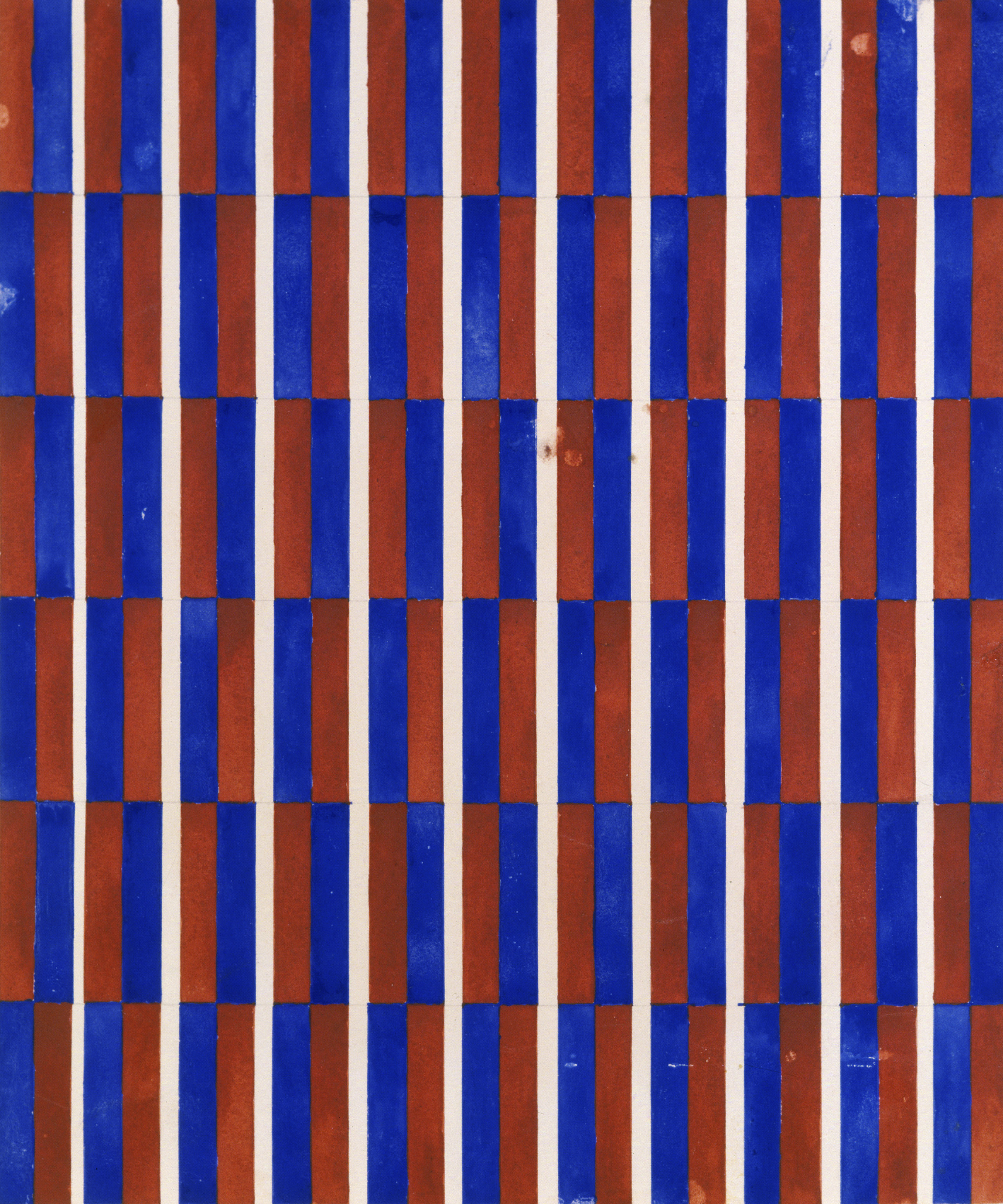

Liubov Sergeyevna Popova, Sketch for Textile, 1923–24 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Private collection, Moscow

Moscow started off as a fortress (Kremlin) and, like most cities, grew by adding merchants’ and artisans’ quarters, protecting them with walls, incorporating more quarters, and building more walls (the Russian город, like the English ‘town’, means ‘a fenced-in place’). Like most Russian cities, Moscow was subject to frequent raids by steppe nomads and jealous neighbors. Unlike most Russian cities, it became a princely seat (favored at a crucial time by the Mongols), the patriarch’s residence (descended from Constantinople), the capital of a Eurasian tsardom (derived from ‘Caesar’), and, according to one theory, ‘the Third Rome’. The rapid ascent of St. Petersburg and the great fires of 1812 (which sent Napoleon on his circuitous way to Waterloo) took some luster away from Moscow but did not slow it down. The Kremlin remained the symbolic center of Russia; walls, ramparts and moats became concentric ‘ring’ roads and boulevards surrounding the Kremlin; mass immigration of former serfs fed capitalist development while filling the ranks of its gravediggers.

The Bolshevik revolution began in Petrograd, but the new government moved to Moscow, transforming it into the Fourth (anti-imperial) Rome‚ the capital of the future. Wars, famines, forced collectivization, and the proliferation of colleges, commissariats, and construction sites brought more immigrants; private apartments became ‘communal’ as new arrivals crammed into every room, nook, and cranny. Old belfries were torn down, crooked alleys straightened, and new constructivist buildings planned and sometimes built. Russia’s largest church, the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, was blown up to make way for the world’s largest building: the Palace of Soviets.

"When the Nazis came within thirty kilometers of the Kremlin, Stalin reviewed the Revolution Day parade on snow-swept Red Square and told the troops to prove themselves worthy of the great mission history had entrusted them with. They did; most died within weeks."

When the Nazis came within thirty kilometers of the Kremlin, Stalin reviewed the Revolution Day parade on snow-swept Red Square and told the troops to prove themselves worthy of the great mission history had entrusted them with. They did; most died within weeks. The metal piles from the half-completed foundation of the Palace of Soviets were used to make anti-tank barriers. The Battle of Moscow sent Hitler on his circuitous way to the bunker.

After the war, German prisoners were paraded through the streets of Moscow and employed in the construction of new straight avenues, grand embankments, and ‘Stalin high-rises’, designed to complement the Palace of Soviets while replacing the four hundred or so demolished churches as the city’s defining landmarks. Only seven were built before Stalin’s death (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Moscow University, Ukraine and Leningrad hotels, and three elite residential buildings). The Palace of Soviets never got off the ground.

Khrushchev’s reign began with the decree ‘On Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction’, which put an end to Stalinist monumentalism, and the speech ‘On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences’, which was delivered three weeks after my birth. The foundation pit of the Palace of Soviets became the world’s largest open-‑air swimming-pool. The room my parents rented in a one-story house on Pushkinskaya Street had a woodburning stove and a leaky ceiling. My earliest memories are of my father chopping logs for the fire and shoveling snow off the roof. One of our neighbors bred rabbits and kept them in little cages in the courtyard.

"Khrushchev’s reign began with the decree On Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction, which put an end to Stalinist monumentalism, and the speech On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, which was delivered three weeks after my birth."

Liubov Sergeyevna Popova, Sketch for Textile, 1923–24 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Private collection, Moscow

Pushkinskaya Street (formerly Bolshaya Dmitrovka, renamed during the Pushkin Jubilee of 1937) ran from the Bolshoy Theater and the Union House to the Pushkin monument on Strastnoy (Christ’s Passion) Boulevard, by way of the mansion where Pushkin lost a fortune at cards, and the Communist Party archive, where I would spend countless hours hoping for something interesting to turn up. The Union House used to be the House of the Assembly of the Nobility, where Liszt and Rachmaninoff dazzled the crowds, my father’s ancestors danced the polonaise, and Dostoyevsky delivered his Pushkin speech, which proved decisive in the canonization of both (on the same day as the mortal remains of Luís de Camões were moved to the Church of Santa Maria de Belém, marking the tricentenary of his death and the beginning of his official canonization). In Soviet times, it was one of the principal venues for solemn state occasions, including the Moscow Show Trials and the lying in state of the Party leaders who died in good odor, including Lenin, Stalin, and Brezhnev.

[...]

Share article