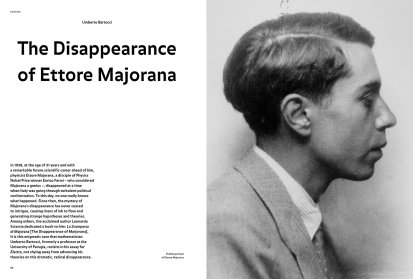

THE DISAPPEARANCE

In 1938, at the age of 31 years and with a remarkable future scientific career ahead of him, physicist Ettore Majorana, a disciple of Physics Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi – who considered Majorana a genius –, disappeared at a time when Italy was going through turbulent political confrontation. To this day, no one really knows what happened. Since then, the mystery of Majorana's disappearance has never ceased to intrigue, causing rivers of ink to flow and generating strange hypotheses and theories. Among others, the acclaimed author Leonardo Sciascia dedicated a book to him: La Scomparsa di Majorana [The Disappearance of Marjorana]. It is this enigmatic case that mathematician Umberto Bartocci, formerly a professor at the University of Perugia, revisits in his essay for Electra, not shying away from advancing his theories on this dramatic, radical disappearance.

Profile portrait of Ettore Majorana © Erasmo Recami and Maria Majorana / Erasmo Recami and Fabio Majorana Collection / Courtesy American Institute of Physics, Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Maryland

Ettore Majorana disappeared suddenly in Naples on the evening of Friday 25th March, 1938 and was never heard from again – at least not officially. In addition to the anguish that typically accompanies such disappearances, especially among family members, this case was particularly important as em (as we shall refer to him from here in) was one of the most brilliant physicists of his generation – a generation, let us remember, which for better or worse worked on the theorisation and use of atomic energy and included Heisenberg (Nobel Prize, 1932), Fermi (Nobel Prize, 1938) and Segrè (Nobel Prize, 1959). EM was well known to all these great scientists. During his physics studies in Rome, he had been particularly close to Enrico Fermi and Emilio Segrè’s group (which also included Bruno Pontecorvo, winner of the Stalin Prize in 1953) and spent a period of time studying in Leipzig alongside Heisenberg in 1932.

EM had only been in Naples for a few months, having been appointed full professor of Theoretical Physics at the Royal University of Naples in the autumn of 1937 ‘for his esteemed reputation of singular expertise’, an honour previously reserved only for Guglielmo Marconi (Nobel Prize, 1909), the inventor of the radio. In short, a rising star of Italian physics who had just turned 31 years old upon becoming a professor (EM was born in Catania in August 1906). We know that he went to the Naples Institute of Physics that fateful morning, despite not having to give any lectures, carrying a briefcase full of handwritten papers. We do not know who he went to meet or what he intended to do with those papers. He handed the bag to one of his students (Gilda Senatore) who was alone in a lecture room studying during a break from lectures (one of the very small group who had decided to attend the new professor’s difficult course) and uttered the following Sibylline phrase: ‘Hold on to these papers for me and we’ll speak later.’ He walked away and they never spoke again. Evidently Miss Senatore fell ill shortly after and was unable to return to the institute for some time, only learning of EM’s disappearance several days later. She showed the papers to her fiancé, Francesco Cennamo, one of the assistants of Institute director Antonio Carrelli, who handed them over to his professor. Erasmo Recami, one of the first to deal with the Majorana case in as systematic and documented way as possible, commented: ‘He turned the path of life into a hierarchical one; so that those manuscripts were lost. An incalculable loss. Perhaps not even Ettore would have been able to calculate it.’ Recami’s comment is curious because it is precisely that ‘hierarchical’ path that could (and should) have ensured, more than any other and vice versa, the preservation of those papers, the history of which is another story within this history, a mystery within the mystery. But let us gloss over it for now and continue.

We do not know how EM spent the rest of the day, either that morning or in the afternoon. What we do know (or think we know) is that, having returned to the hotel where he was staying, he left at around 5 p.m., probably with his passport and a certain amount of money (that day he had collected all his wages for the first few months of his new university career, which he had never bothered to collect before; EM was from a wealthy family and had no particular need for money). It is believed that he intended to embark on the steamer ‘Città di Palermo’ of the ‘Tirrenia’ company, which ran between Naples and Palermo, but from that moment on he was never seen or heard from again.

Ettore Majorana (indicated by the arrow) with his classmates during a break at the Instituto Massimo, run by the Jesuits, in Rome, c. 1914 © Erasmo Recami and Maria Majorana / Erasmo Recami and Fabio Majorana Collection / Courtesy American Institute of Physics, Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Maryland

"He had then left on a table in his hotel room a note addressed ‘To my family,’ containing only these few lines: ‘I have only one wish: that you do not wear black."

the singular manner of the disappearance

So far a disappearance like many others, one might say, for which the novel by another famous Sicilian, Luigi Pirandello (Nobel Prize, 1934), The Late Mattia Pascal (1904), is called to mind, but EM wanted to complicate things. That same day he had sent director Carrelli a letter, to be delivered the next day, in which he wrote: ‘I have made a decision that has by now become inevitable.’ He had then left on a table in his hotel room a note addressed ‘To my family,’ containing only these few lines: ‘I have only one wish: that you do not wear black. If you want to bow to custom, wear some sign of mourning, but for no more than three days. Afterwards remember me, if you can, in your hearts and forgive me. Affectionately, Ettore.’

Having arrived in Palermo (as far as we understand), he sent two telegrams: one to his hotel in Naples, asking to keep his room, and the other to director Carrelli with the message: ‘Do not be alarmed. Letter to follow. Majorana.’ In fact, an ‘express’ letter had left Palermo at the same time with the words:

‘Dear Carrelli, I hope you received the telegram and letter together. The sea has rejected me and I will return tomorrow to the Hotel Bologna, travelling perhaps with this same travel document. However, I intend to give up teaching. Do not take me for an Ibsenian girl because the case is different. I am at your disposal for further details. Regards,

E. Majorana.’

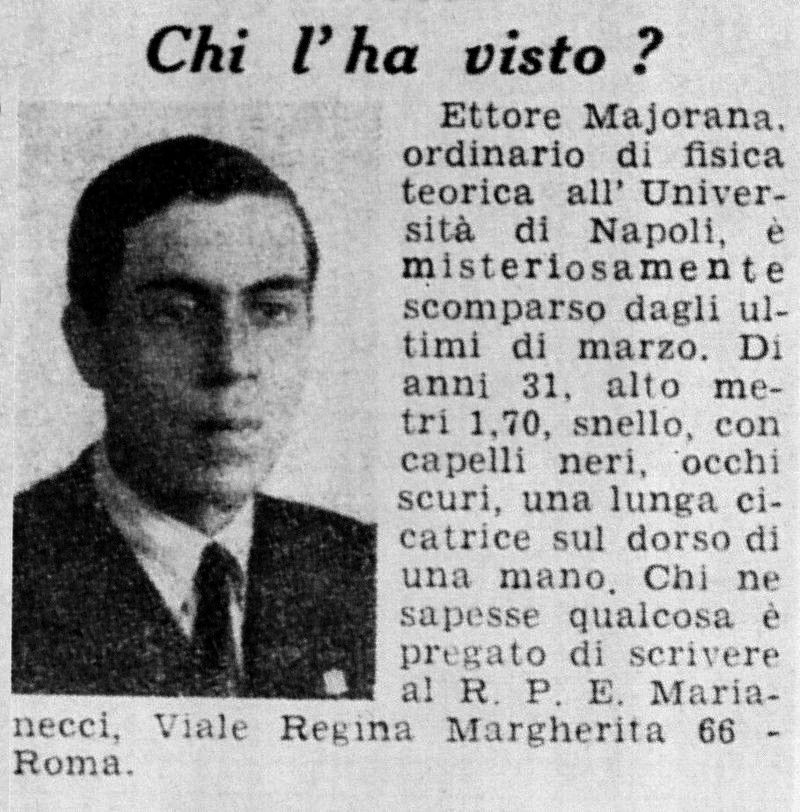

The announcement of Majorana’s disappearance published in Domenica del Corriere: ‘Ettore Majorana, professor of theoretical physics at the University of Naples, mysteriously disappeared during the last days of March. 31 years old, 1,70 metres tall, thin, black hair, dark eyes, a long scar on the back of his hand. If anyone has any infor- mation about him, please write to the R.P.E. Marianecci, Viale Regina Margherita 66 – Rome.’

Carrelli recounted that he first received the telegram on the morning of Saturday 26th, then a few hours later the letter of the 25th, the one sent from Naples (a letter in which EM ‘manifested suicidal intentions’, in Carrelli’s words). On Sunday 27th he had finally received the express letter, which was evidently meant to reassure the addressee, but there was no further news of EM thereafter. Carrelli reported the disappearance to the Police Chief of Naples on Thursday 31st March, while the day before he had informed the Rector of the University of Naples in a ‘highly confidential personal letter.’

What happened to EM between 25th and 26th March, 1938? Was he really in Palermo, travelling on the steamer ‘Città di Palermo’ on the night between the 25th and 26th? And from Palermo did he then return to Naples? And if so, when exactly?

[...]

Share article