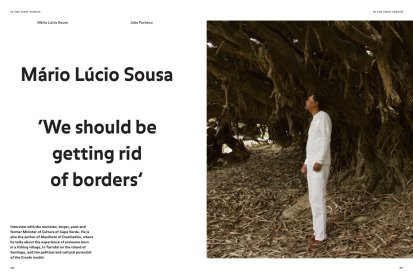

A musician and writer who lives between Brazil and Cape Verde and has won major awards, Mário Lúcio Sousa started writing before he went to school, scratching letters on the ground in the village of Tarrafal, where he was born in 1964. During his years as Cape Verde’s Minister of Culture, he meditated every day on the dangers of power. If he begins writing in Portuguese, you know that a book, such as the novels O Novíssimo Testamento [A Brand New Testament], O Diabo Foi Meu Padeiro [The Devil was my Baker] and Biografia do Língua [Biography of Língua], could soon be on its way. If the words are written in Creole, it is because he is composing a new song.

Interview with the musician, singer, poet and former Minister of Culture of Cape Verde. He is also the author of Manifesto of Creolisation, where he talks about the experience of someone born in a fishing village, in Tarrafal on the island of Santiago, and the political and cultural potential of the Creole model.

JOÃO PACHECO Are you a child of the sea?

MÁRIO LÚCIO SOUSA Physically, yes. I was born beside the sea in a fishing village called Monte Iria in Tarrafal de Santiago. But also because of Yoruba cosmogonies and from a Creole ethnological perspective too. Creoles belong to the Atlantic. The Atlantic has formed this new third identity.

JP In your book Manifesto a Crioulização [Manifesto of Creolisation], you wrote: ‘The past can imprison a culture’.

MLS The past holds you back. If you’re unable to project your shadow, it can undermine you. There are various cultures for whom the past is their only reference point, and you can live hundreds of thousands of years like that. But what we’re seeing in the modern age is that it becomes a source of irreversible conflict, because it’s a noose around your neck. So, what happens to this projection? As soon as you can free yourself from the past without rejecting your reference points, you can build the future. Because it opens us up to other possibilities, other encounters. When you take the past as a reference point on which to build and not as something on which to build reference points, you free yourself and are able to build a future identity. Basically, humans have been engaged in a single battle ever since they appeared on the face of the earth: a constant struggle to hold on to what they know and to confront what they call the ‘new’. The new challenges our very existence, and just as well it does, for life would be unremittingly dull without it.

JP You moved into a military barracks at the age of ten. How did you parents agree to that?

MLS I still ask myself that today, and I still thank them for what they did, morning and night, in my daily meditations. There’s no way to explain it, because I was very close to my mother. We were similar, both of us were quiet. As a child, I’d spend hours playing with ants while my mother watched me. Then, when I was ten, something happened when I was reading poetry on the porch at the side of the house. I was summoned by the twilight. I left the house and walked at least a kilometre and a half until I reached the sea, where I couldn’t read anymore. When I climbed back up, I met Mário Elísio, an officer in the military, and he asked me why I wasn’t at home. I told him I had been reading poetry, which he thought was strange. I hid the book, but he told me to read it, to which I replied that I knew it off by heart. So, I recited it and he was amazed.

JP What was the book?

MLS Nôte, by a poet whose pseudonym was ‘Kaoberdiano’. He died recently. His real name was Felisberto Vieira. He was one of the first people to write protest and revolutionary books in Creole. I recited the poems in the book and the man asked me where I lived. He took me home and talked to my parents. I heard him say that they had to make sure I got a good education, because it wasn’t normal for someone of my age to be able to recite a book like that. I remember my mother replying by pointing at her forehead and saying: “Hmm, he was born like that…”

JP He’s a bit crazy…

MLS Yes. But he said: ‘The state would like to give this boy a special education.’ And I said I wanted to go. So, that very same night, I went with Mário to the barracks located in the Tarrafal concentration camp.

JP Which was no longer a concentration camp.

MLS That’s right. The camp had been liberated in May 1974, and I arrived in May or June 1975. I remember that a few months later I entered the school, which was a hundred metres from the camp. I moved into the officers’ residence, where the former camp director used to live. It was a beautiful house. I’d never been in a house with a bathroom before.

JP Is that where you lived?

MLS Yes. That’s when my life took the path, due to literature and writing, that it’s been on ever since. I’m a father and I ask myself how parents could let a child of ten leave home with someone they didn’t know. I remember the scene. It was the first time I’d ever seen my mother and father sat next to each other. It was as if they were waiting for something and, with complete serenity, they let it happen. The following year, my father died and three years later my mother died too. There were twelve of us at home and it was the money from my scholarship that supported us all.

JP When your parents died, did you still find time to work as a letter-writer for people who couldn’t read and write?

MLS That was a bit earlier. I was probably in 2nd or 3rd year, eight or nine years old. My brother, Eurico, did it before me, until he went to study in Praia.

JP But was it a job?

MLS It was unpaid community work. There weren’t many kids who knew how to read, but my father made sure we all went to school. I took on my siblings’ duties of writing letters to people in the army in Angola – there were a lot of lads from my neighbourhood fighting in the army in Angola and Guinea – and to husbands working abroad.

JP Did you write in Portuguese?

MLS Yes, they wouldn’t have trusted me if I didn’t. It was an incredibly innocent age. I remember the things they used to ask me to write: ‘Tell him that Pintada the cow is pregnant.’ That was major news in 1971. I remember the terrible drought years. I remember a cousin of mine coming from faraway on foot under a scorching sun to bring my grandmother a pumpkin. We ate that pumpkin, boiled in water, for several days. It was a very difficult time. I wrote what they wanted me to. The women spoke in Creole and I translated it into Portuguese, followed by a ritual I used to love. I had to read the whole letter back to them in Portuguese, and they would confirm whether it was correct. They could understand Portuguese when they heard it, but they couldn’t speak or write it. I became a kind of community worker, counting parallelepipeds, helping to share out money, dividing up the fish after the catch came in… Anything to do with sums and writing was my area. There is something intrinsic about my relationship with words and literature.

JP What was the first religion you believed in?

MLS Catholicism. I was baptised in the church of Santo Amaro Abade in Tarrafal, and I went to Catholic Church for some time. I remember going to mass. Then, I left home at ten and I changed to the Church of the Nazarene. By myself. It was more fun; there was more singing. In the Catholic Church, there was the church choir. They rehearsed and the ritual was different. The faithful didn’t participate, they just repeated what was said. At the Church of the Nazarene, it was great, because they had musical instruments. They had a guitar and an organ and they let us play them. They gave us a copy of the New Testament, and, after a while, they gave us a Bible. That was my first book. I loved reading the New Testament, which is why I wrote Novíssimo Testamento [A Brand New Testament].

[...]

Share article