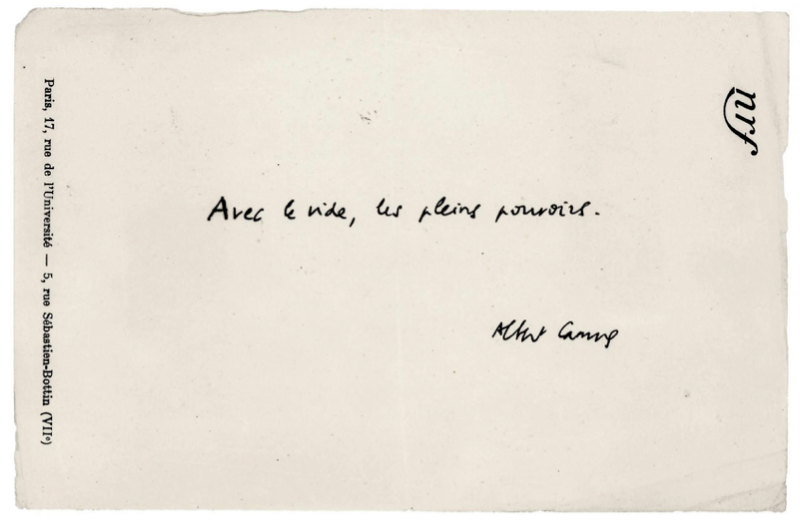

On 28 April, 1958, Paris saw the opening of an exhibition by Yves Klein titled La Spécialisation de la sensibilité à l’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée [The Specialisation of Sensibility in the Raw Material State in Stabilised Pictorial Sensibility]. The opening was a roaring success. As this was also the artist’s thirtieth birthday, a huge group gathered at 9pm at Galerie Iris Clert, on rue des Beaux-Arts 3, in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. With great delight Yves Klein later said that by 9.45pm the crowd was such that he could no longer move. The event’s success was entirely justified given the unusual nature of the work on show. Aside from the long (somewhat inaccessible and cryptic) official title, the exhibition also had another abridged designation which describes more accurately the only object on display: Le Vide. Albert Camus attended the show and left a brief note ‘Avec le vide, les pleins pouvoirs.’ [‘With the void, full powers.’]

To show the void is already a highly transcendent experience, however, the opening proved also to have a rather ironic aspect since the exhibition’s main object – the void – vanished as soon as the gallery’s only room began filling up with guests. The void ceases to be a void as soon as it is filled. Two years later, the void conspicuously reappeared in another iconic Yves Klein work. The photo‑ graphic montage Le Saut dans le vide [The Leap into the Void] shows the artist leaping into an empty space. Around the same time, the void became the centre of his monochrome works and, from 1960 onwards, it became the main reference for the Nouveau Realisme group in France and group ZERO in Germany, who both sought to establish new ways of perceiving reality. In other words, the representation of the void served to awaken a greater spiritual awareness in the viewer. The void was not seen as horror vacui or philosophical nihilism, but as an attempt to reproduce an immanent beauty pointing to a reality that (supposedly) lies beyond the physical: tà metà tà physiká. In that sense, an empty gallery or a monochrome painting represent a question that transcends human epistemological abilities. How to show the void? The question cannot be answered philosophically. The void vanishes as soon as an observer tries to observe it, because there is always an immediate and immanent relationship between the observer and the observed. The observer is part of the observed; positing the observer’s real existence means that he cannot observe the void without involuntarily filling it with his own presence. The void is a paradox, i.e. does the void (or nothingness) really exist?

Share article