I will begin by delineating my conception of the political. I have suggested distinguishing between the political, which is linked to the dimension of antagonism present in human societies – an antagonism that can emerge within a large variety of social relations –, and politics, which aims at establishing an order and organising human coexistence under conditions that are traversed by the political and thus always conflictual. We find this distinction between the political and politics in other agonistic theories, though not always with the same signification. We can in fact distinguish two opposing ways of characterising the political. There are those for whom the political refers to a space of liberty and common action, while others see the political as a site of conflict and antagonism. It is in those conflicting understandings that we can find the origin of the fundamental divergence between the different agonistic theories. The thesis I defend is that it is only when the ineradicable character of division and antagonism is recognised that it is possible to think in a properly political manner and to face the challenge confronting democratic politics.

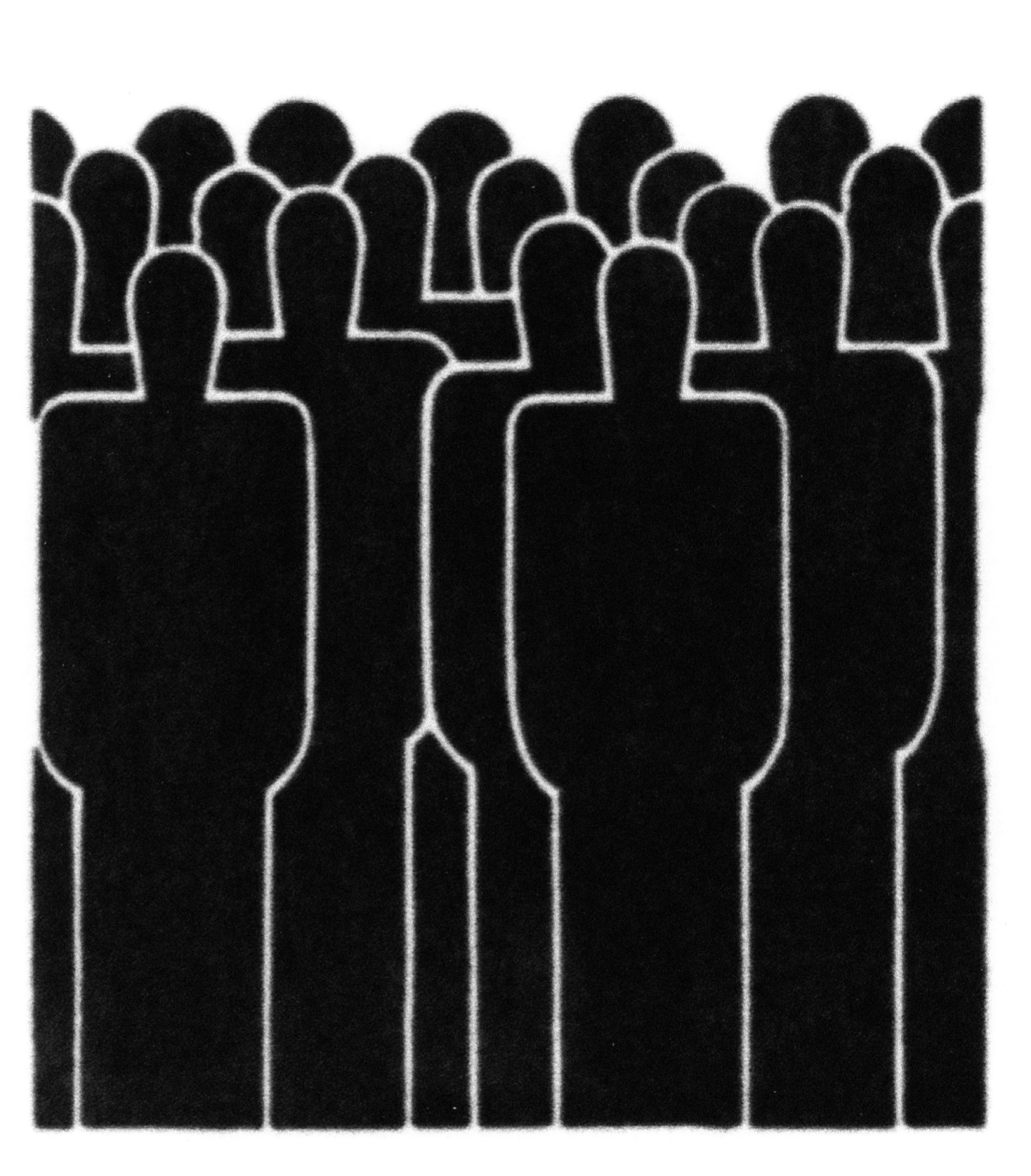

Taking account of the dimension of the political signifies acknowledging the existence of conflicts that cannot have a rational solution; this is exactly what is meant by ‘antagonism’. To be sure, not all conflicts are of an antagonistic nature, but properly political ones are because they always involve decisions which require a choice between alternatives that are undecidable from a strictly rational point of view. Political life will never be able to dispense with antagonism for it concerns public action and the formation of collective identities. It aims at constituting a ‘we’ in a context of diversity and conflict. Yet, in order to constitute a ‘we’, one must distinguish it from a ‘they’ and there is always the possibility that, in certain conditions, this we/they would take the form of an antagonistic friend/enemy confrontation. This is why I have argued that the crucial question for democratic politics is not to reach a consensus without exclusion – which would amount to creating a ‘we’ without a corresponding ‘they’ – but to construct the we/they discrimination in a mode which is compatible with democratic institutions. This is something that most liberal democratic theorists have to elude due to the inadequate way they envisage pluralism. While recognising that we live in a world where a multiplicity of perspectives and values coexist and that it is impossible, for empirical reasons, that each of us would adopt them all, those theorists imagine that, brought together, these perspectives and values, constitute a harmonious and non-conflictual ensemble. This type of thought is therefore incapable of accounting for the necessarily conflictual nature of pluralism, which stems from the impossibility of reconciling all points of view, and this is why it is bound to negate the political in its antagonistic dimension.

According to the ‘agonistic’ model that I have developed in several of my writings, to conceive pluralist democracy in a way that does not deny the antagonistic dimension supposes envisaging two possible modes of manifestation of the antagonistic dimension: as a friend/enemy confrontation or as a confrontation among adversaries. It is the latter that I have proposed to call ‘agonistic’. The agonistic confrontation is different from the antagonistic one, not because it allows for a possible consensus, but because the opponent is not considered an enemy to be destroyed but an adversary whose existence is perceived as legitimate. Their ideas will be fought with vigour but their right to defend them will never be questioned. The category of enemy does not disappear, however, for it remains pertinent with regard to those who, because they reject the conflictual consensus that constitutes the very basis of pluralist democracy, cannot form part of the agonistic struggle. The question of the limits of pluralism is therefore a crucial one for democracy and there is no way to escape it.

The distinction between antagonism (friend/enemy relation) and agonism (relation between adversaries) allows us to understand why, contrary to what many democratic theorists believe, it is not necessary to negate the ineradicability of antagonism in order to visualise the establishment of a democratic order. In fact, the agonistic confrontation, far from representing a danger for democracy, is in reality the very condition of its existence. Of course, democracy cannot survive without certain forms of consensus, relating to allegiance to the ethico-political values that constitute its principles of legitimacy, and to the institutions in which these are inscribed. But it must also enable the agonistic expression of conflict, which requires that citizens genuinely have the possibility of choosing between real alternatives.

Share article