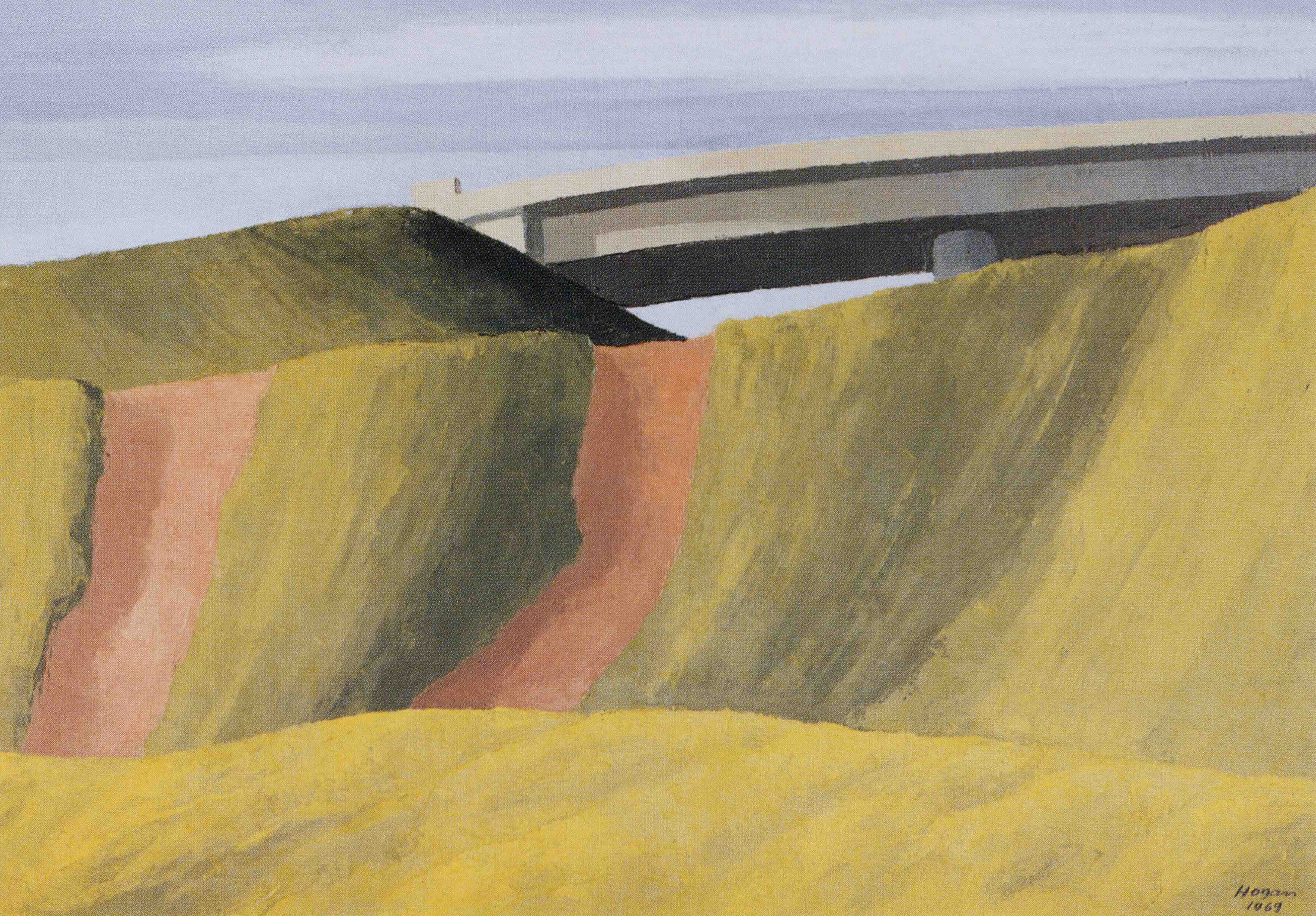

Jorge Gaspar, geographer and urban planner, Professor Emeritus of the University of Lisbon, collector of contemporary Portuguese art. Together with his wife Ana Marin, he also promotes and funds a programme of exhibitions and residencies for young artists in Alvito, where he owns a second house that is home to a significant part of this collection. Gaspar knows the Portuguese territory in depth, from cities to countryside, its geography, history and culture. When he starts talking about these subjects, he seems like a sophisticated map of physical and human geography, full of lines, forms and colours. If we want to find a personality who is comparable in his scientific field, Orlando Ribeiro, who was his teacher, is perhaps the name that immediately comes to mind.

This interview focuses on a specific topic: the city and the countryside, its differences and geographical and historical continuity. It took place in the Institute of Geography and Regional Planning, in the Cidade Universitária campus, where Jorge Gaspar still has an office. Through this conversation, we learn that his relationship with the area where the university rectory stands today, as well as the lawn that goes down to Campo Grande, is very old – it is part of his ‘novel of origins’ and not only of his academic life. There he spent his childhood (before becoming the heart of the university campus, that territory was a family farm). This interview could have started here: not long ago, the cosmopolitan city of knowledge was an agricultural field.

To begin the interview, Jorge Gaspar came prepared with an anthology of quotes, passages of Eça de Queiros’s The Illustrious House of Ramires and especially The Maias, but also of a novel by Agustina Bessa-Luís, where the countryside is evoked, represented and described. These quotes were used by Jorge Gaspar to show the occurrence of the countryside as a topic extensively represented in literature, where its definitions vary historically according both to aesthetic-cultural values and the history of urban planning. Since the Renaissance invented the concept of landscape, the countryside has become the object of many metamorphoses and aesthetic figurations. Of the many quotes chosen by Jorge Gaspar, which could constitute the corpus of a thematic study, we transcribe this excerpt of The Maias:

Share article