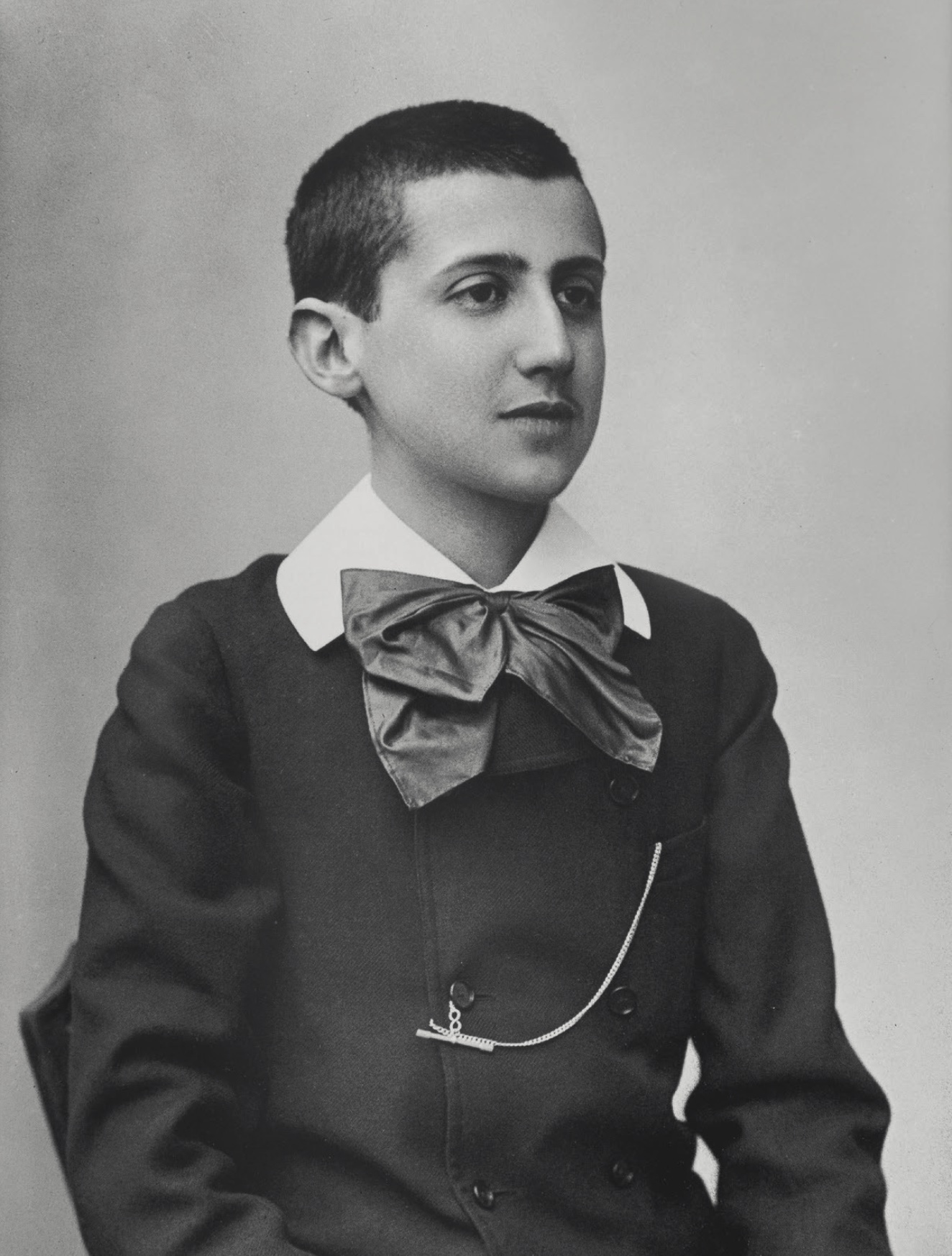

A century after his death (1922), and just over one hundred and fifty years after his birth (1871), Marcel Proust is now recognised as one of the most important writers of the 20th century. His unique mode of novel writing paved the way for the Nouveau Roman, while the way his life fed his desire to write and enriched his work also make him a precursor of autofiction. Writers refer to it frequently and columnists are wont to quote it, sometimes without even having read it; the episode of the madeleine1 arises in the most banal broadcasts, newspapers and conversations, illustrating the singular experience of a memory that resurfaces involuntarily by means of a sensation. Proust has become a name that does the rounds, an episode familiar to all, a novel that is read – in part2 –, certain stereotypes: long sentences, the madeleine (again), homosexuality, jealousy, snobbery, the chronicle of a society undergoing a metamorphosis; Proust is at the same time a landmark, a model, a reference: a brand.

Our depiction of the writer, stemming from the Enlightenment and Romanticism, leads us to see in him a style, a universe, an essence, a pure spirit, indeed everything but a man. Structuralism, by teaching us to detach the text from its very source and from the context in which it was written, has transposed the ‘elocutionary disappearance of the poet’ into literary criticism and literature studies3. To this can be added the distinction that Proust himself makes between the social self and the creative self in certain drafts published under the title By Way of Sainte-Beuve: ‘A book is the product of a different self from the self we manifest in our habits, in our social life, in our vices’4.

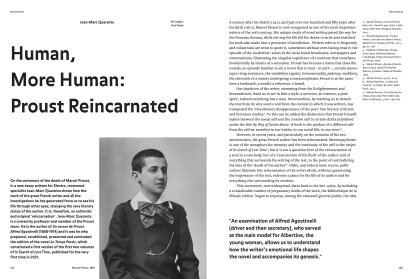

However, in recent years, and particularly on the occasion of his two anniversaries, the great French author has been reincarnated. Metempsychosis is one of the metaphors for memory and the continuity of the self in the incipit of In Search of Lost Time5, but it is not a question here of the reincarnation of a soul in a new body, but of a ‘resurrection of the flesh’ of the author and of everything that surrounds the writing of the text, to the point of contradicting the idea of the ‘death of the author’6. Older, and indeed more recent, publications illustrate this reincarnation of the writer which, without questioning the importance of the text, redeems a place for the life of its author and for everything else surrounding its creation.

Share article