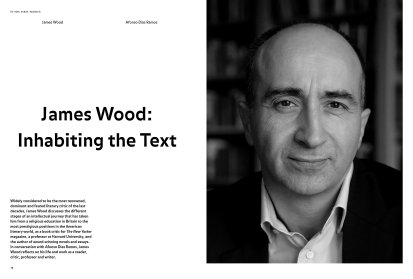

James Wood is widely acclaimed as the leading literary critic in the Anglo- -American world. Born in 1965, in Durham, UK, he studied at Eton with a scholarship in music and at Cambridge. Currently, Wood is Professor of the Practice of Literary Criticism at Harvard University and a staff writer and book critic at The New Yorker. He was the chief literary critic at The Guardian and a senior editor at The New Republic. His essays and reviews regularly appear in the New York Times, New York Review of Books, The Guardian, and the London Review of Books. James Wood inspires more fear and loathing in the English literary world than any other critic at work today. Once called the ‘elegant assassin’ by Boston Globe and a ‘courtly eviscerator’ by n+1, he is generally considered to be the most feared man in American letters, renowned for his brutally direct reviews that were a trademark of his early career. This reputation owes to scathing essays that range anywhere from the dismantling of Paul Auster’s hypermasculine swagger to the indictment of John Updike’s intellectual slackness, from the critical takedown of popular writers, such as Toni Morrison, Julian Barnes and Jonathan Franzen, to the searing analysis of the encyclopedic novels by Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace as a ‘hysterical realism’, which is to say an obsession with the noise of the topical and with prolonged digressions in order to avoid silence, character, and reflection.

At a time when criticism seems to have been reduced to book reviews done as hack work by academics or would-be writers puffing up their friends and sneering at their enemies, James Wood is a rare thing: a professional full-time literary critic. This is not the only reason why he appears to come from another era. Advocating an aesthetic approach to literature, rather than more ideologically-driven trends in academic literary criticism, his models are not Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man, but Edmund Wilson, Ernest Renan and Matthew Arnold, and the novel is held out to be a secular form of scripture that emerged as the distinctions between religious and literary belief began to blur. As writers and theologians started to look at the Gospels as fictional tales — no longer prized as literal truth, but as poetic imagination and moral edification — novelists turned literature into a quasi-religion. That is why ‘novelists’, Wood argues, ‘should thank Flaubert like poets thank spring’. These insightful elucidations have yielded essays on canonical writers (Melville, Chekhov, Cervantes) and recent legends (W.G. Sebald, Marilynne Robinson, Teju Cole), which have been held out as a standard for informed and insightful appreciation, promoting a slow-motion approach wrapped in a distinctive literary style of their own. Lately, Wood has been more of a populariser, credited with bringing Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and Ben Lerner — and, with them, the hybrid essayistic style now often called ‘autofiction’ — to wider public attention. With three decades of literary criticism under his belt, Wood has no shortage of detractors, and the knives were certainly waiting for his own novels. But nonetheless, these books did secure a great deal of critical attention. At the same time, a number of writers have publicly acknowledged their profound appreciation for his reviews, for being attuned to deep resonances and currents in books that even the authors were unaware of, which in some cases, such as Zadie Smith’s, has even led them to change their own approach. Martin Amis, for instance, described him as ‘a marvellous critic, one of the few remaining’. Cynthia Ozick declared that ‘James Wood has been called our best young critic. This is not true. He is our best critic; he thinks with a sublime ferocity.’ Long hailed by Harold Bloom, Susan Sontag and Christopher Hitchens as something of a successor, no other critic alive today holds the same level of prominence and influence, scrutiny and antagonism. Wood’s critical essays have been collected in The Broken Estate: Essays on Literature and Belief (1999), The Irresponsible Self: On Laughter and the Novel (2004), The Fun Stuff: And Other Essays (2012), and recently, Serious Noticing: Selected Essays, 1997-2019 (2019). In 2000, he received the Academy Award for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in 2009 he won the National Magazine Award for Criticism. He has authored two acclaimed novels, The Book Against God (2003) and Upstate (2018), as well as a study of novelistic techniques, How Fiction Works (2008). James Wood has talked to Electra about his life and his work, in a series of reflections on thirty years of reviewing, teaching, writing and thinking about books.

Share article