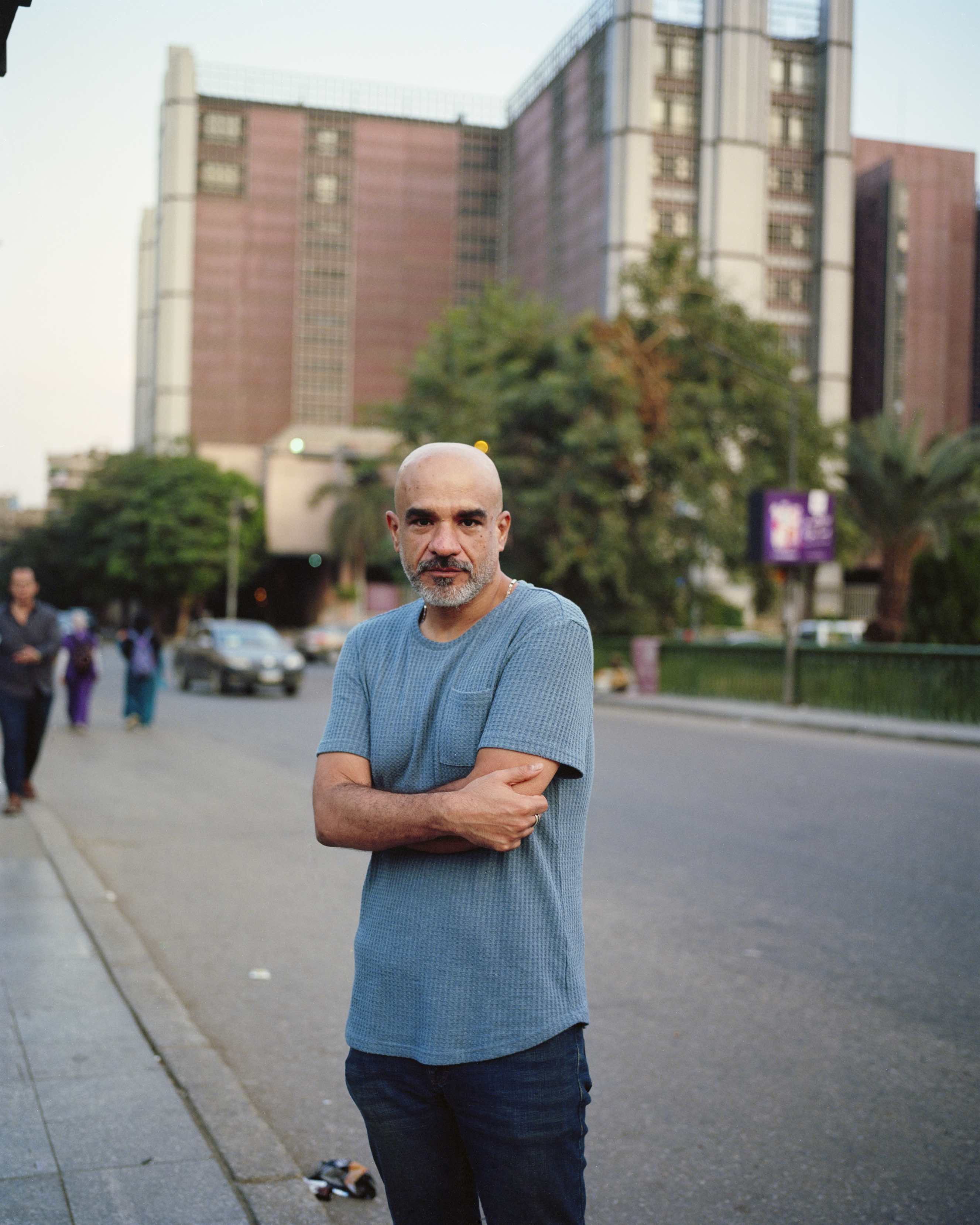

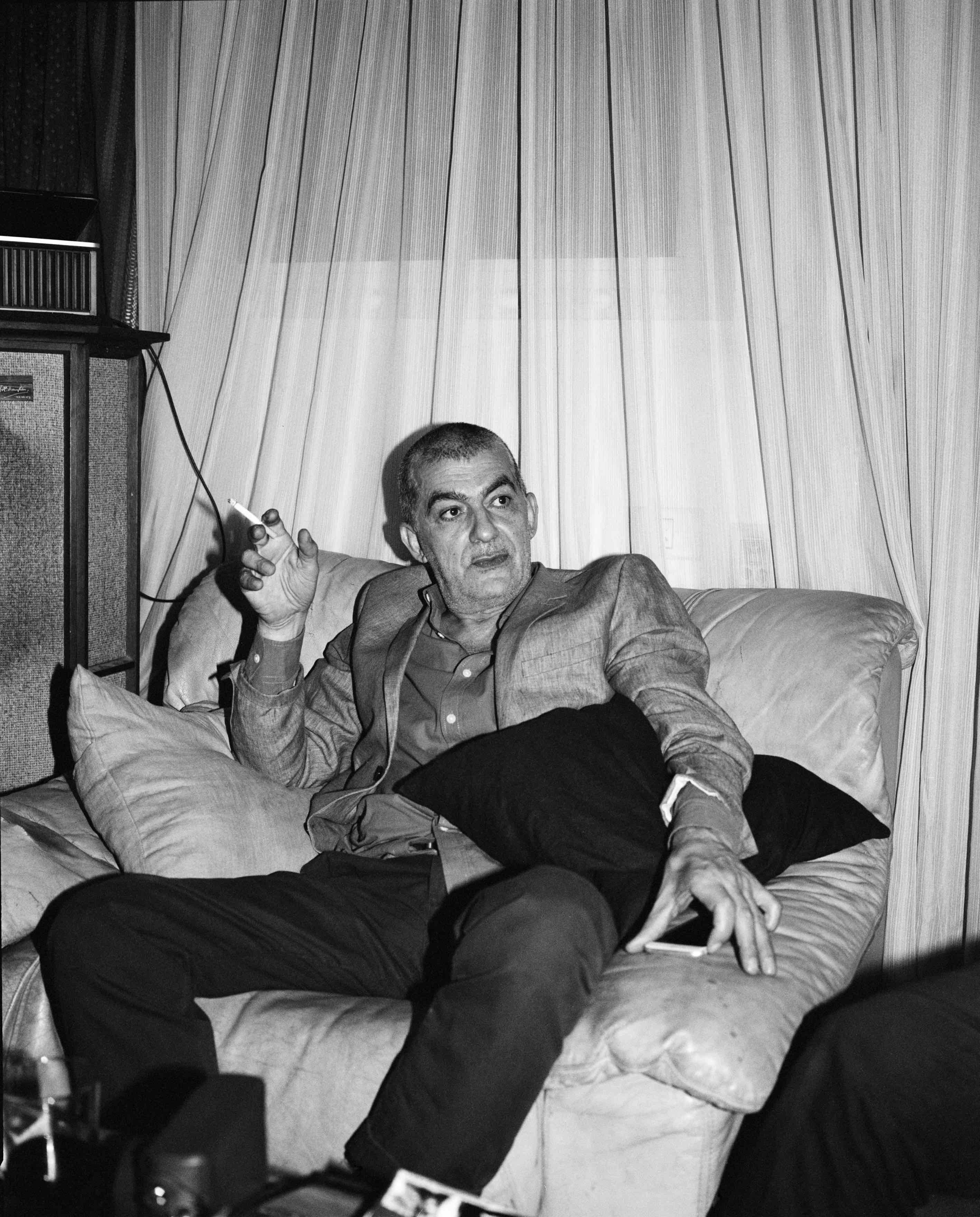

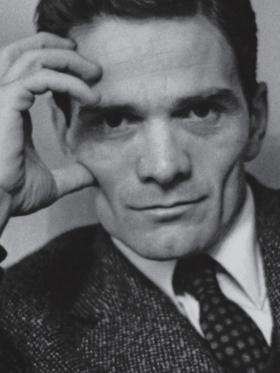

Youssef Rakha (born on 12th June, 1976, in Cairo, Egypt) is an Egyptian writer.

The only child of a formerly Marxist lawyer, Elsaid Rakha, and an English- ‑to-Arabic translator, Labiba Saad, Rakha was born and grew up in Dokki, on the western bank of the Nile, where he lives with his family today. At the age of 17, he left Egypt for the UK, where he obtained a first class honours BA in English and Philosophy from Hull University in 1998. On his return he joined the staff of Al-Ahram Weekly, the Cairo-based English-language newspaper, where he has worked regularly since 1999.

Rakha is best known for his first novel, The Book of the Sultan’s Seal: Strange Incidents from History in the City of Mars. First published in 2011, the book is studied for its innovative use of Arabic, its postmodern take on the theme of the caliphate, its reimagining of the city of Cairo and its possible significance in the history of Arabic literature.

Since 2011, Rakha has completed two other novels in a proposed trilogy on the January Revolution, The Crocodiles and Paulo. The latter was longlisted for the ‘Arabic Booker’ in 2017 (the International Prize for Arab Fiction) and won the 2017 Sawiris Cultural Award for Best Novel, in January 2018.

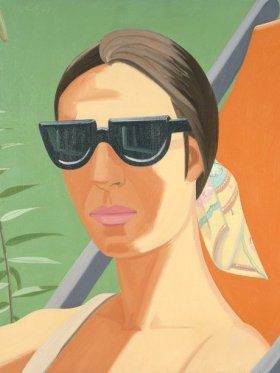

Rakha is also known as a photographer and the editor of a bilingual literature and photography site. He contributed to the coverage of Arab culture in English for many years as a reporter, literary critic and cultural editor.

His work explores language and identity in the context of Cairo, and reflects connections with the Arab-Islamic canon and world literature. He has worked in many genres in both Arabic and English, and is known for his essays and poems as well as his novels. He is a well-known literary figure in Cairo and Beirut.

Share article