The process of establishing, spreading and consolidating football in Rio de Janeiro was framed by the complex and contradictory relations involving, on the one hand, the clubs of the social elite in the rich neighbourhoods of the Zona Sul [South Zone] and on the other, the working class clubs beside the railway lines serving the suburban regions where most of the workers lived.1 The distance between the clubs in these two football worlds was not just geographical but also social and racial, demarcating the symbolic frontiers of a game of power which football was both invested in, reinforcing it in many ways, and opposed to, subverting it in crucial areas.

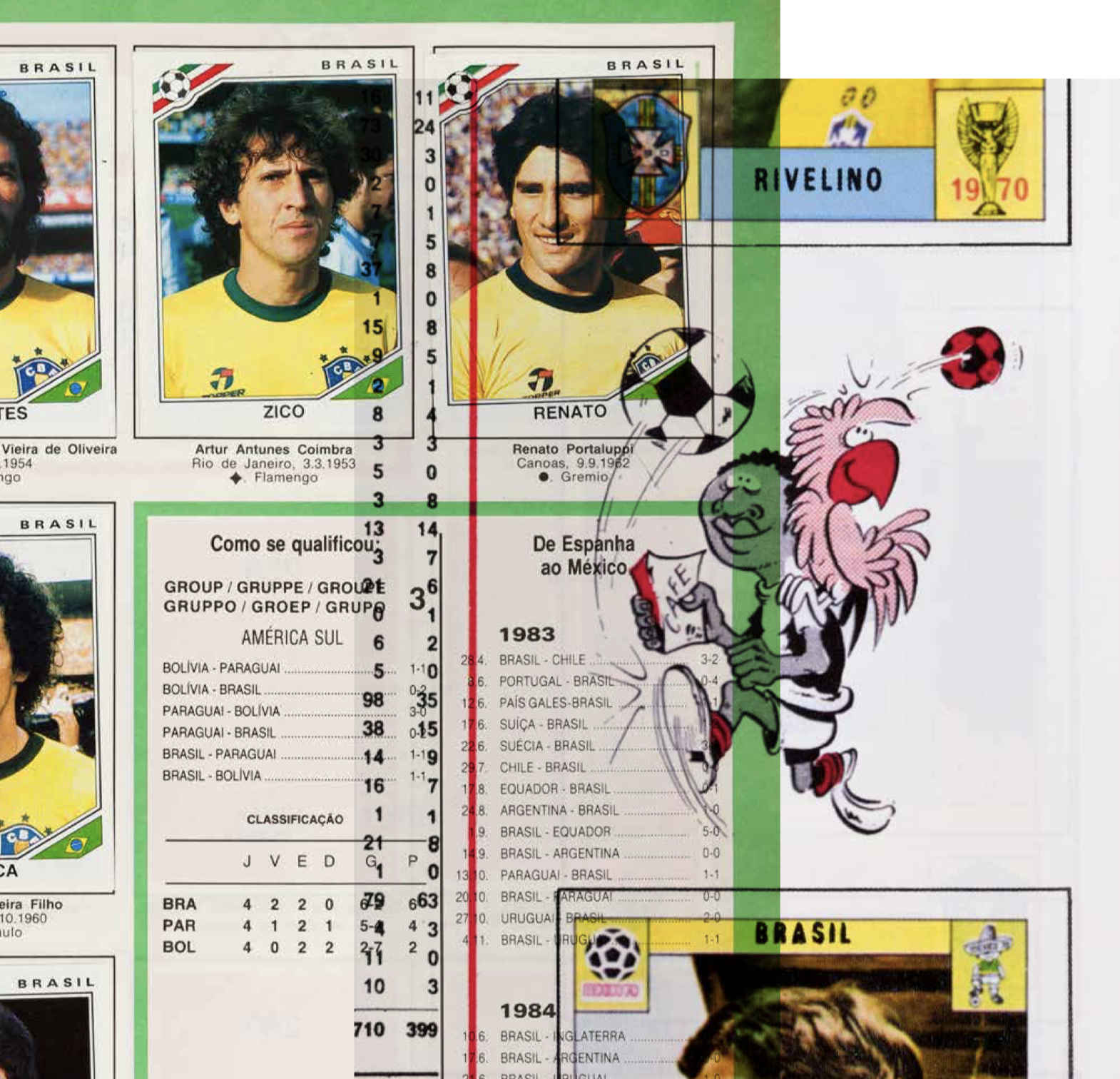

As the popularity of this European sport grew in Rio, the main clubs in the city – Flamengo, Botafogo, Fluminense and Vasco da Gama – began recruiting more and more players from the distant suburbs, neighbouring cities and even from the favelas, the shanty towns scattered across the hills surrounding the Zona Sul. Resistance to the presence of poor and black players in the teams of the social elite was slowly overcome by a pragmatic calculation driven by the agonistic appeal of the spectacle, which represented a change in stance justified by the ideology of racial democracy propagated in the country since the 1930s.

The correlated narratives of Brazil as the country of football and racial democracy were mutually reinforcing, projecting a distorted and idealised notion of Brazil both internally and externally that would become clearer after the country’s success at the 1958 World Cup. In the newspaper Jornal dos Sports, the writer and playwright Nelson Rodrigues stressed the historical value of that sporting feat: ‘Many might think, with absolute obtuseness, that Sweden was just about the success of a football team.’ That would be a mistake, according to the author, for whom 1958 was above all the ‘victory of all the downtrodden and neglected people in Brazil’, among whom he highlighted the ‘pingente da Central’.2

Nelson Rodrigues’s comment is a perfect example of the narrative behind the construction of Brazil as a footballing nation, followed by the sport’s symbolic power to redeem the Brazilian people. In addition to these two interlinked aspects, however, the writer also focuses on the pingentes on the Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil [Brazilian Central Railway]. Familiar to the local residents, the pingentes were a feature of the urban landscape and aroused mixed feelings of anxiety and admiration, both glorified in the lyrics of samba music and loathed by the newspapers. In fact, the papers contained news about them every day, albeit relegated to the crime pages. Therefore, we will look more closely at the pingentes, since, as I hope to show, it will take us to the heart of the footballing mythology created after Brazil’s triumph at the World Cup in 1958.

Share article