JUNE 16TH, BLOOMSDAY

LISBON-MUNICH

Almeida Faria’s literary oeuvre is made up of different genres and registers, sometimes in the same novel. This is the case of Paixão, the first book in his ‘Lusitanian Tetralogy’, which is almost a polyphonic novel in its complex development of different voices. This time, he has made an incursion into journalling at the invitation of the Electra. The journal that he wrote for this section of the magazine, called ‘Book of Hours’, begins on a triumphant day, 16th June, the Bloomsday that Joyce included in the calendar of modern European literature. Thus, this journal starts as a tribute to literary fiction, to its magnificent deeds (a tribute which continues in an evocation of an important name in European literature, a European writer par excellence, the German Hans Magnus Enzensberger, 118with whom Almeida Faria has a long-standing dialogue). Recording a few days’ stay in Munich, starting with the day of his departure from Lisbon and ending on his return, this journal is also a record of his distancing himself from national matters. In a way, this distancing, which consists of getting away (and by away we mean to a foreign country) and casting a critical, cosmopolitan, look inwards, isa mechanism common to the narrative work of Almeida Faria.

Hoping to escape the dreaded virus and its retinue of variants that follow us urbi et orbi, with no relief in sight, I submit my chronically blocked nostrils to the near mission-impossible of breathing through a mask. When, in a moment of youthful folly, I bought a modern replica of the pointy-nosed masks worn by Venetian doctors during the Black Death, it never occurred to me that I would one day be surrounded by faces half-covered by distinctly uncarnivalesque masks.

Before my country’s return to democracy, flying was, for me, pure euphoria; it meant escaping the whiff of mothballs, the nationalistic bell jar of the proudly alone that still echoes in the Portuguese are best. Flying meant turning my back on the lethargy of a hypocritical, paralysed society, sloughing off the weight of the world and of myself.

Now, though, flying has become a test of patience and stamina. A combination of a febrile desire for filthy lucre and a consumerist frenzy has transformed vast areas of Lisbon’s modest airport into a kind of hastily thrown together bazaar, like a jacket that’s too tight on the shoulders and arms. From the security controls to the departure gates we are obliged to follow a long meandering path overstuffed with shops and more shops packed to the gills with wines and spirits, perfumes, cigarettes and other useless items, as well as the inevitable pastéis de nata, those calorific bombs promoted as icons of national identity.

"Before my country’s return to democracy, flying was, for me, pure euphoria; it meant escaping the whiff of mothballs, the nationalistic bell jar of the proudly alone that still echoes in the Portuguese are best."

Passengers dawdling erratically along this path suddenly come to an abrupt halt to make a phone call or send a last-minute message; they photograph everything in sight, and when they’ve run out of photographable objects, they photograph themselves. If being up close to all this frenetic excitement has its risks, boarding an overcrowded plane is even riskier. Taking our masks off only to eat, sitting wedged into narrow rows of seats, squashed together for hours in an enclosed space in which we all breathe the same supposedly filtered air, has little to recommend it. To be avoided.

In the seat in front of us, an arrogant, burly individual coughs and coughs again, making no attempt to suppress that stubborn cough. What strange times these are when a cough or a sneeze can fill us with such alarm! The couple in seats A and B in our row neither talk to nor touch each other, but instead, as if hypnotised, they caress, stroke and paw the tiny rectangular screens of their mobile phones with an almost erotic tenderness. I must be the only person gazing out of the window. No one else is interested in watching the fast-vanishing earth or the clear skies or the convulsive explosions and implosions of clouds:

Arnold Böcklin, Isle of the Dead, 1880

Passing away imperceptibly they have no notion of dying.(.............)

Probably they believe in resurrection, thoughtlessly happy like me (..............)

Indeed, they mutate incessantly, overnight, resourceful creatures, non-violent.

A History of Clouds, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, trans. Martin Chalmers and Esther Kinsky

If I look long enough at those inconstant clouds, those celestial nomads in a state of constant flux, I begin to see figures, ghosts, faces: a bold Icarus falling from the roof of the world because the sun has melted his wax wings

insignificantly off the coast there was

a splash quite unnoticed this was Icarus drowning

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, William Carlos Williams

In a particularly plump, curvaceous cloud, I imagine I see Ganymede, who, in Antiquity, was deemed to be the most beautiful of young mortals. He was coveted by Zeus, who wanted to whisk him off to Mount Olympus, and who, true to his reputation as a master of disguise, transformed himself into an eagle in order to abduct him. Rembrandt had great fun subverting this myth by painting a rather ugly, squalling brat of a Ganymede literally peeing himself with fear as he is carried off through the air in the firm grasp of the beak and talons of that fickle, mutable god of gods.

The skies have always attracted and intrigued us humans. From my scant readings of the Bible, I remember Jacob’s ladder connecting the earth with the garden of the clouds, as Lourdes Castro calls it. In the days when there were still plenty of angels, those angelic beings, archaeologists of the soul, would climb down that scala paradisi, then climb up again, helping the finer souls to ascend:

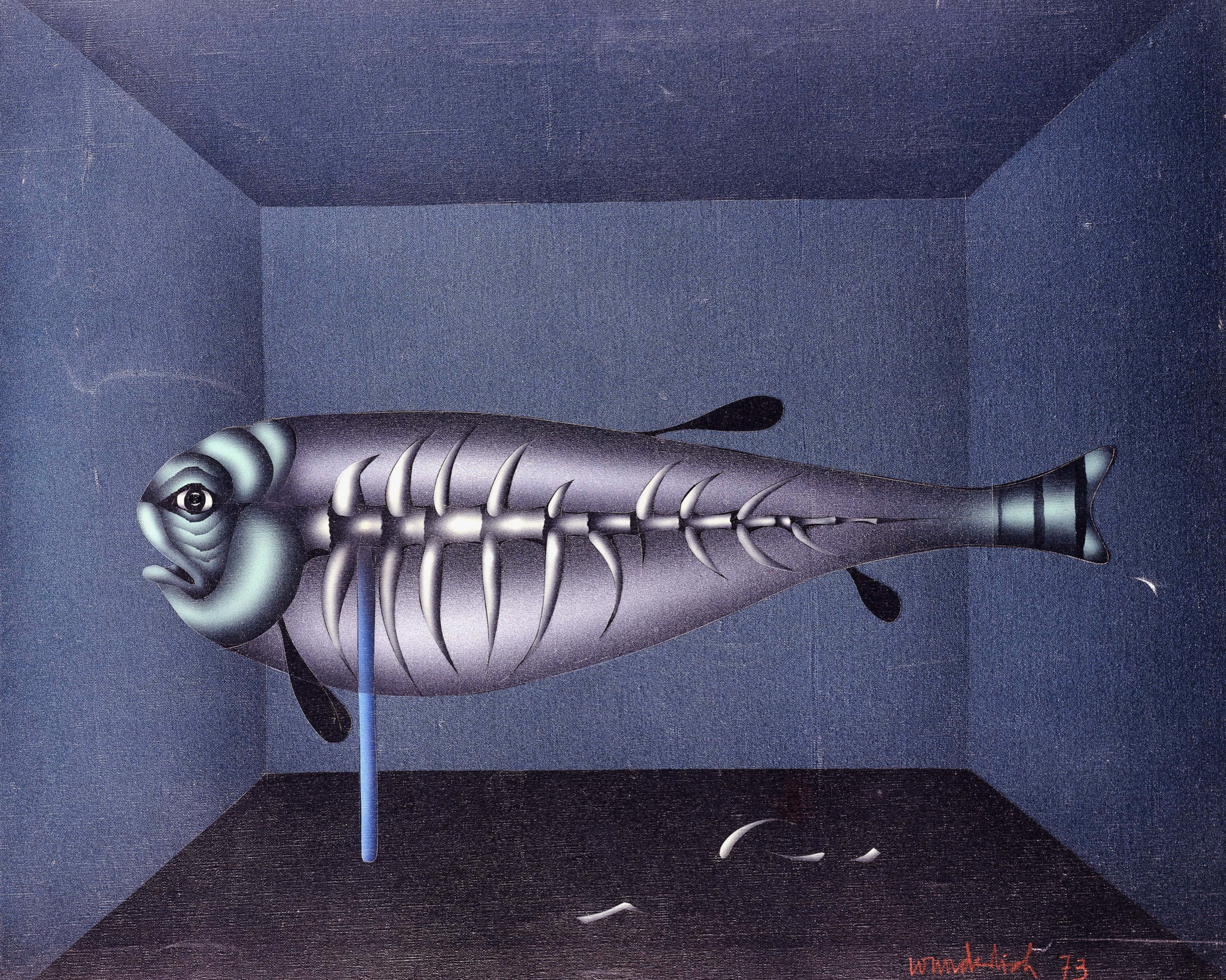

Paul Wunderlich, Fish form, 1973 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Christie’s Images, London

The angels were once as plentiful As species of flies. The sky at dusk Used to be thick with them. You had to wave both arms Just to keep them away.

In the Library, Charles Simic]

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than dreamt of in your philosophie.

Wearying of my idle task as contemplator coeli, I briefly closed my eyes, and when I opened them again, we were flying over the luminous south of France and snowy Switzerland, with Mont Blanc rising up from a sheet of snow, grey in the blue afternoon light. Shortly afterwards, Bavaria hove into view, like an imitation of an old Flemish painting: intensively farmed fields like ample gardens, bluish-green reservoirs, forests of chestnut trees among others I can’t identify. As the plane lost height to come in to land, I could make out bushes thick with pale flowers like the remains of a most improbable snowfall in this almost-summery Bavaria.

That night, I drink a glass of Bavarian beer in honour of the Bloomsday we celebrated in Dublin years ago with Hélia, Luísa, and Paulo Castilho. It was, people say, on that very date that Nora, James Joyce’s future sweetheart and the future Molly Bloom, said: I made Jim a man. Regardless of whether or not the fact and the phrase were invented, I like to think of that one lascivious moment on 16th June in 1904 setting in motion Joyce’s novel-cum-monument with Leopold Bloom at its centre – a profane and profaning epic, an iconoclastic celebration of the erotic encounter between Catholic Ireland and its remarkable ironic inheritance. Bloomsday must be unique: a day dedicated not to a god, or to a saint, or to some historical or legendary figure, but to a literary character.

[...]

Share article