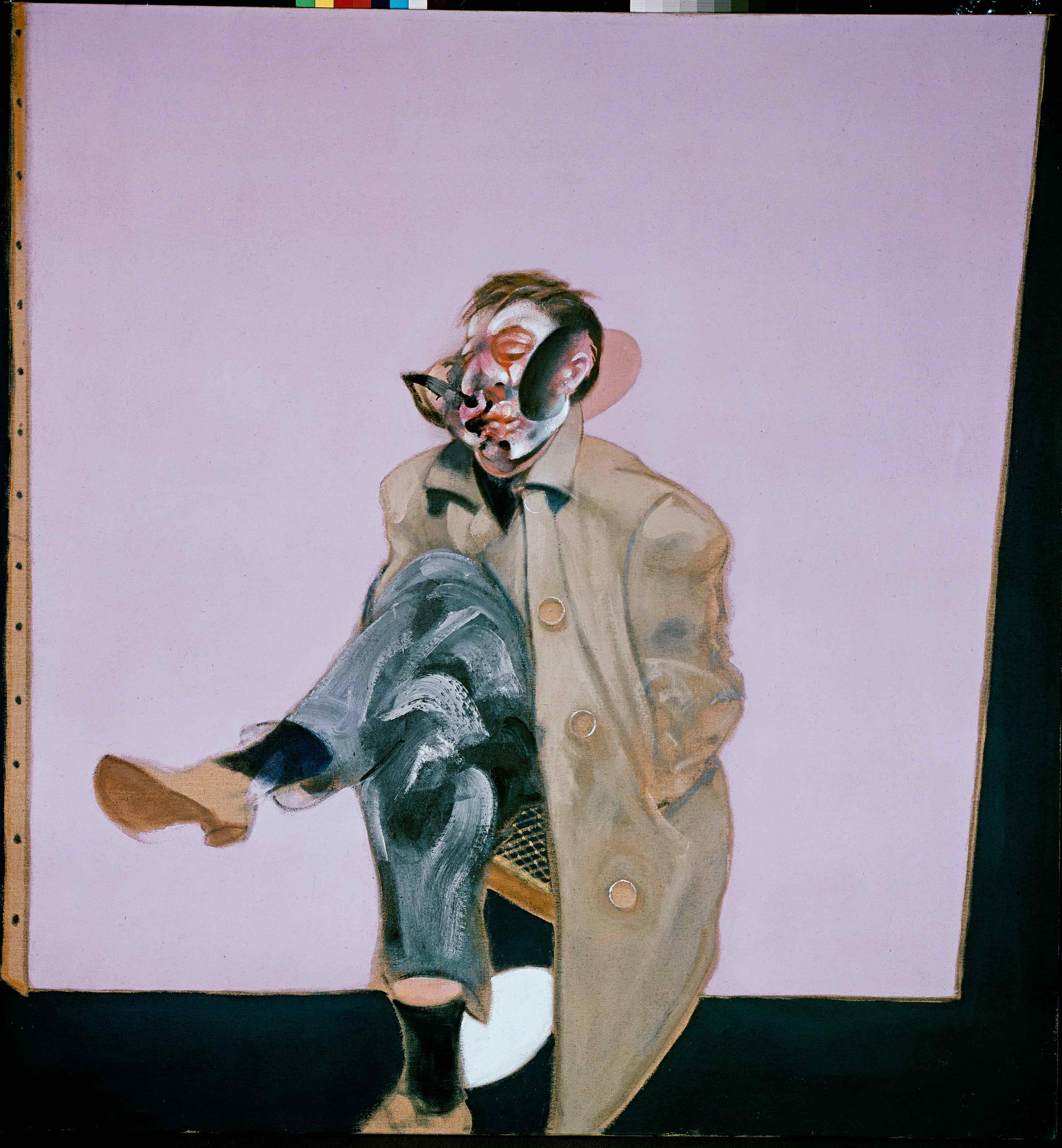

Such was Andy Warhol (1928-1987), whom philosopher Anne Cauquelin called ‘a false modern, a true contemporary’. His opinion of art did not belie what he did with art and for art, rather it confirmed it with a deliberate and challenging eloquence. In one of his aphorisms, which tended to blend value judgements and reality judgements, he declared: ‘Success is what sells’, a statement joined by others such as: ‘Art is already advertising. The Mona Lisa could have been used as a support for a chocolate brand, Coca Cola or anything else.’ Or else: ‘I think that all paintings should be the same size and colour, so that they are interchangeable and no one thinks that his picture is better or worse than others.’

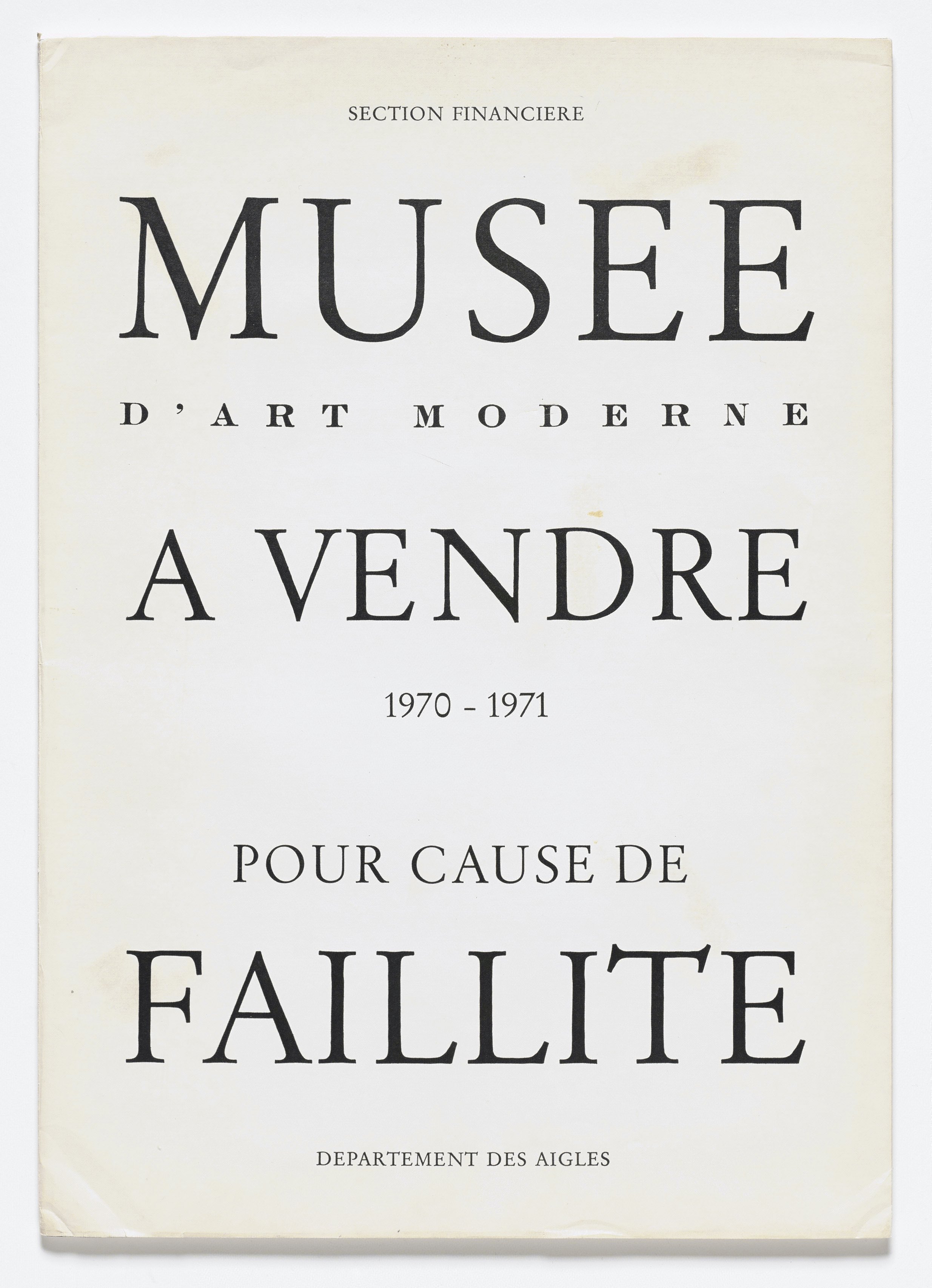

For this great performer and printer of the stereotyped image with which he presented himself to the world, the meaning of his words extended into the meaning of his works. He brazenly proclaimed aloud what he practiced with the most provocative disdain, confessing, ‘I will go to the opening of anything, including a toilet seat.’ In declaring that ‘Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art’, he explained: ‘Buying is more American than thinking’, and predicted that ‘Someday, all department stores will become museums, and all museums will become department stores.’ For him, art and the business of art were inseparable and came together as a two-sided coin, each face bearing traces and signs of the other.

As we know, the words modernity and post-modernity, as historical periodisations, cultural categorisations and artistic classifications, are always apt to be discussed and controverted, giving rise to an endless industry of symposiums, seminars, debates, talks and other forms of dense and inconclusive occupation of hours and minutes. Nevertheless, we can use them to say that, in the passage from modernity to post-modernity, the artist who made these and other surprising claims (in a vein already followed by Salvador Dalí, though affording it an extreme and far-reaching dimension), announced what is currently before our jaded eyes.

In his elegant indifference, he exhibited himself as one of the great, provocative symbols of Pop Art. However, in his words and deeds, the founder of the Factory became more than just the most silkscreened face of a movement or a school. He reached the heights of a precursor who predicted (and premeditated) the future of art following his reign as king, crowned with a golden crown which shone as only fake gold can.

Andy Warhol had a gift for reaching where he wanted to be by taking the road in the opposite direction. For him, the world was the ghost of art, which was the ghost of the world, and money (as a convention-fiction more real than any reality) was the only thing linking them, with the artist as best man of this mercantile wedding or the guarantor of this creative business.

The art that followed in those years after Warhol changed the idea of art, speaks of crisis – the crisis of art –, even when it remains unspoken. Contemporary art rests upon a subsoil of crisis and critique, which turn weaknesses into strengths. So it was with the author of the electric chair, repeated ad nauseam in one of his most celebrated series, a veritable emblem on the worn-out lapel of time.

To speak of what Andy Warhol spoke of, and to do it as he did, is to speak of contemporary art: of money, sales, purchases, openings, success, advertising, marketing, communication, power, i.e. of the system within which art is made, and which defines, judges, values, enshrines and, according to some, threatens it. Is this indeed what contemporary art is? Everything that can be said about it ends with a question mark; with questions that are given as answers to other questions.

Contemporary art, along with the system that it produced in which to embed itself, is now one of the most powerful global devices to seize and understand our time. Since the founding purpose of Electra is to trace the lines of the moving portrait of ’our great epoch’, in this issue we could not fail to dedicate a whole dossier to contemporary art, incomplete and provisional as it might be.

What is this art that calls itself contemporary, with a passionate obsession and sovereign consciousness of itself? Under which conditions is it made, in which circumstances is it produced, shown, imposed, commercialised and globalised? What is the engine that drives and steers it, giving it speed, acceleration and mutability? Which metabolisms ensure its life, growth and cellular reproduction?

What system do we speak of when we speak of this system composed of a proliferation of centres, museums, galleries, studios, private and public spaces, networks, biennials, triennials, festivals, auctions, openings, closings, conferences, talks, publications, performances, happenings? Which mechanisms support its symbolic, institutional and fiduciary legitimation? And which are the centrifugal and centripetal forces shaping its circles of certification, consensus and enshrinement, ensuring the consistency of its validity strata and the velocity of its valuation circuits? What are the roles of artists, mediators, curators, programmers, producers, curators, gallerists, marchands (now called dealers), managers, communication directors, publishers, collectors, patrons, critics, historians, journalists, commentators, influencers, financial funds, speculators, and how are they performed in this play whose stage is the world, taking immanence for transcendence and the instant for eternity? Amid so much proliferation, so much repetition, exhibition and saturation, where it seems that everything has already been shown and seen, experimented and explored, how is it still possible for creation, invention, novelty, originality, awe and the future to emerge?

André Malraux (1901-1976), lived through, and testified to, the great tragedies of the 20th century. Thanks to an unfaltering disposition – the very axis on which balanced his need for contemplation and his urgency for action – he nervously wrote thousands of pages on art, searching without end. Malraux was a sort of counter-Warhol, though both shared the divine gift of mystification.

While the American sought to debase, trivialise, normalise, desacralise, massify, materialise, sensationalise, exteriorise, decode, demystify, moderate (some would say: mediocratise), mediatise and commercialise, the Frenchman sought to elevate, aggrandise, exceptionalise, singularise, spiritualise, interiorise, codify, canonise, sublimate, protect, sacralise and mystify. While the former turned everything into a human comedy, the latter turned everything into a divine tragedy. Yet both shared an animal instinct of listening to the breathing of the universe.

A statement-prediction is attributed to Malraux that he might never have actually spoken or written. Thanks to this misunderstanding, which no one was ever able to put out of circulation, we are left in a mine-field at the entrance to which we could be welcomed by the slow-moving shadow of Jorge Luis Borges, who enjoyed confusing the clues and blurring the boundaries between the authentic and the apocryphal, the true and the false, the real and the imaginary. At the end of that same mine-field, bidding us farewell, is the tightrope-walking figure of Andy Warhol, who falsified his birth certificate and loved the fake copy of the images that turned the world into a repetitive hallucination. For him, frivolity was a form of lucidity, fame a substance of art, lightness a mask of gravitas, the mundane a metaphysical category, the ephemeral a condition of the eternal, and banality a characteristic of the visionary.

What Malraux was supposed to have said, but never did, was a copy without an original or an authenticated signature. More than anything else he might have said, that fake quote spread across the world and, after so many years, came to stand in time like a statue to voluntary and voluntaristic credulity. It became one of the most widespread dictums on the planet. It turned into one of the most believed and quoted truths in the world. Warhol, whose Prado Museum story might after all be as authentic as Malraux’s phrase, would have been envious of this falsity, which seemed to carry with it a truth truer than the truth of truths, given the fact that it was invented, either intentionally or at random, to faithfully reproduce the oracular, prophetic and tragic tone of its apocryphal, but plausible author.

The phrase-dictum attributed to the author of The Imaginary Museum states that ‘The 21st century will be spiritual [another version reads ‘religious’] or it won’t be at all.’ Endless exegetes made use of this to remind us that for Malraux the religious and spiritual aspect was art itself, the metamorphosis of the gods and the anti-destiny of men and women.

For the writer of The Human Condition, ‘The only domain where the divine is visible is that of art, whatever name we choose to call it.’ Roger Caillois deciphers, in the author of The Voices of Silence, a Promethean notion of art: ‘He maintains the certainty – half-presage, half-challenge, in equal parts protest and consolation – that while the gods did not make man immortal, the latter have a means of proving how timid the former were and, thereby, of mitigating their curse.’1 That ‘means’ is art, but Malraux’s idea of art would give Warhol cause for icy, mocking laughter.

This laughing game – or is it a cold war? – sparked by everyone’s opinion of what art might or might not be, finds shelter in the aspersion, which is at least slightly Warholian in its intention, cast by Malraux on Marcel Duchamp and his descendants and successors: ‘The Mona Lisa smiles because everyone who drew her moustaches died.’

In the end, Malraux was the forced and failed soothsayer of the art of our time, of contemporary art; Warhol was its voluntary prophet and visionary. For this art without canon, perhaps the sole absolute is money, and its religion a fiduciary one. Malraux once said that ‘art is the currency of the absolute’. And so, in one of those twists Warhol was fond of, the currency of the absolute became the absolute of currency – which is also a new form of the sacred. At the end of the day, the sayings attributed to them share a common point of intersection in a symmetry where the past and the future lie in wait.

Unsurprisingly, in this dossier on contemporary art, money, to a greater or lesser degree, is among the themes that play their part in the unextinguishable ‘quarrel of contemporary art’. This quarrel, which some have tried to quell in vain by undermining it, continues to resound in echoes, replicas, returns, metamorphoses and new outbreaks – which are themselves active on the pages of this issue.

This shows how manifold are the modes of seeing and perceiving the path leading from the Dadaists, from Kurt Schwitters and Marcel Duchamp, until reaching us, passing along the way, among many others: Warhol and Pop Art and gallerist Leo Castelli; raw art and informal art; kinetic art and Op Art; minimalism and counter-culture; Pollock and abstract expressionism and Joseph Beuys and the Fluxus movement; Rauschenberg and the combine paintings and conceptual art; hyper-realism and Body Art; Arte Povera and the trans-avant-garde; Keith Haring and Bruce Nauman; Basquiat and Robert Smithson; Louise Bourgeois and Gerhard Richter; Land Art and Ecological Art; urban art and graffiti; and Digital Art.

Some think that, in our time, art has been given the media and the languages, the techniques and the concepts, the qualities and defects, a new paradigm as well as new paradoxes, for it to be exactly what it is and what it needs to be. This is the art of a society in which everything is massified, specialised, relativised, merchandised, disenchanted, desacralised, secularised, trivialised, consumed; where everything is sensation, money, ephemeral, spectacle, fashion, network, and fame. Those who cannot understand this do not understand what goes on in the world of our time and the time of our world.

However, others believe that contemporary art holds all the impossibilities for our time to become great, lasting, perennial, profound, memorable, eternal. For these, art has turned the now into the axis around which it constantly spins, as if everything began and ended there. For that reason, they say that art is amnesiac and ludic, concealing a serious disenchantment of the world with the facile and futile entertainment of the beings that inhabit it.

Still others think contemporary art, by virtue of wishing to be contemporary and not wanting to miss the train of time, has forgotten the wise and subtle advice of philosopher Giorgio Agamben, which we quoted in the editorial of Electra 1:

Share article