1.

On the centenary of Clarice Lispector’s birth, Ricardo Domeneck, a Brazilian poet, visual artist and critic based in Berlin, revisits this great Ukrainian-born Brazilian writer and analyses the period in which she lived and how this is reflected in her timeless work. Surprisingly, Domeneck refers to Lispector as ‘political’, in the atypical sense of the word: that which is prior to and predates ‘the city of men’. Her work opens onto other worlds, and its words have a new resonance that brings a seemingly novel beauty to her melancholic and elegant photographs.

Portrait of Clarice Lispector by Maureen Bisilliat, 1969

© Photo: Acervo Maureen Bisilliat / Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo

One hundred years on from Clarice Lispector’s birth in a tiny village in the Ukraine, before her journey across the Atlantic Ocean to Brazil – a journey made willingly or unwillingly by many others – what more, amidst the whirlwind of Brazil’s political instability and with a global apocalypse looming apparently ever closer to the human and other species, can her writing say to us today?

Lispector’s writing was not removed or immune from the ongoing turbulence of Brazilian politics, and neither did it emerge unscathed. Her first book, Perto do coração selvagem [Near to the Wild Heart] (1943), emerged in the final years of Getúlio Vargas’s Estado Novo dictatorship, and the last book to be published during her lifetime (just a few months before her death in 1977), A hora da estrela [The Hour of the Star], appeared during the civil-military dictatorship, when the Alvorada Palace, the seat of the Brazilian government, was occupied by the general Ernesto Geisel. The Estado Novo persecuted and arrested authors such as Graciliano Ramos, Dyonélio Machado and Jorge Amado, but Lispector was young, the regime was coming to an end, and the intellectual openness of the following two decades was favourable for the reception of her books, although only the first received significant attention.

"Lispector’s writing was not removed or immune from the turbulence of Brazil’s political life of recent decades, and neither did it emerge unscathed. Her first book emerged in the final years of a dictatorship, and the last book to be published during her lifetime appeared during a civil-military dictatorship."

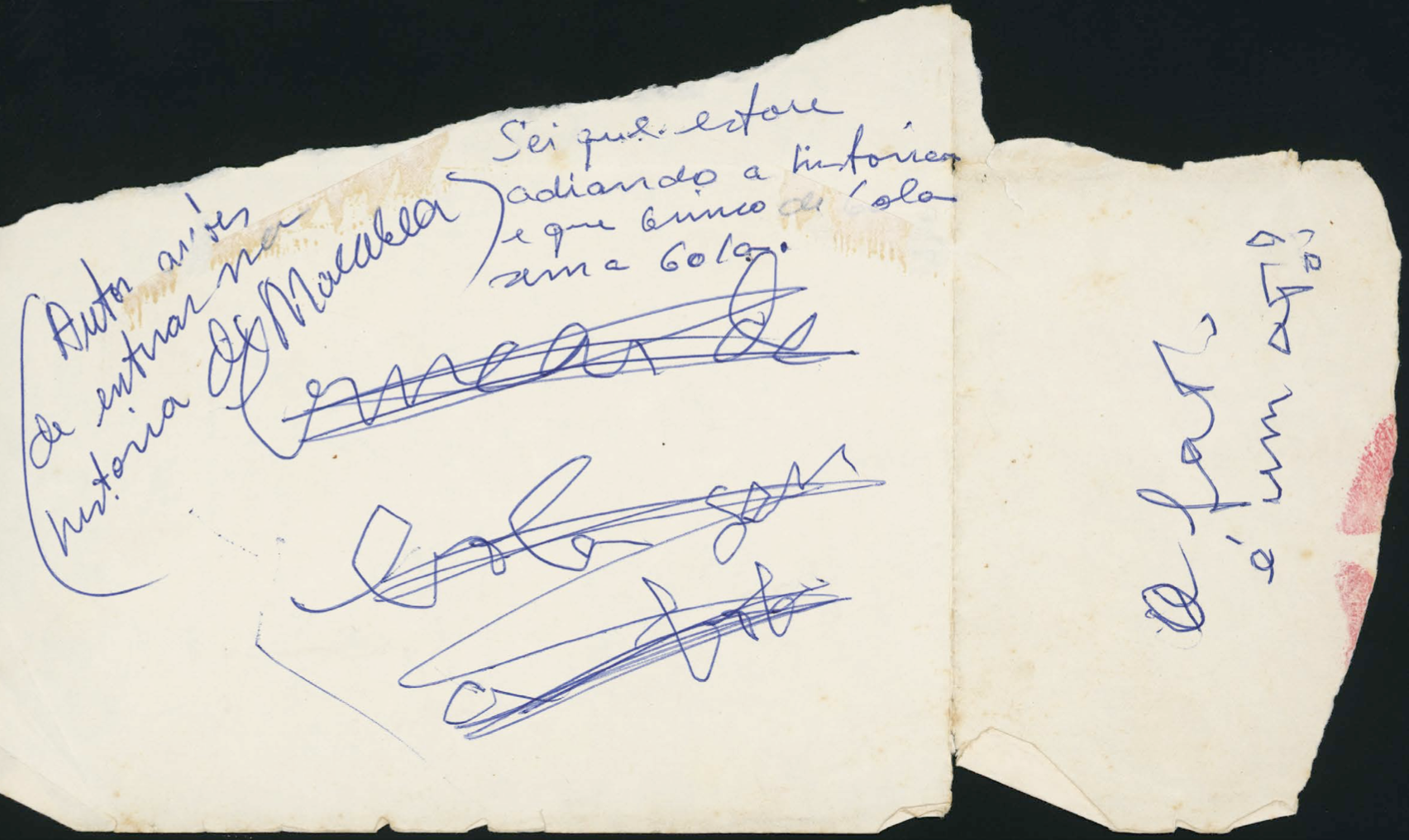

Note used for A hora da estrela [The Hour of the Star]:

‘Allegro com brio.

I’ll try to wrest gold from charcoal.

I know that I’m putting off the story and playing ball without a ball.

Is the fact an act?’

By the end of the Estado Novo, Lispector had left Brazil, and so she didn’t live through the country’s seesaw of stability and instability: the government of Eurico Dutra; the turbulent return of Getúlio Vargas to power and his suicide; the so-called golden years of Juscelino Kubitschek and the construction of Brasilia; the birth of the Bossa Nova, and the coming of age of Brazilian modernism. Lispector took part in this coming of age outside the country, producing novels such as O lustre [The Chandelier] (1946), A cidade sitiada [The Besieged City] (1949) and A maçã no escuro [The Apple in the Dark], written during the 1950s but not published until 1961. The Apple in the Dark seems to me a key book in Lispector’s trajectory, despite often being eclipsed by her masterpieces of the 1960s, and in particular the short story collection Laços de família [Family Ties] (1960) and the novel A paixão segundo G.H. [The Passion According to G.H.] (1964).

It is in The Apple in the Dark that what I would call her political contribution, in the strict sense of polis, the organisation of living human bodies in one geographical space, and her violent criticism of our notions of civilisation and justice begins to take shape. What makes this notion of politics as communal organisation of living bodies more complex is that Clarice Lispector, like other writers of her generation – I’m thinking here of João Guimarães Rosa and Hilda Hilst in particular – also included non-human bodies in this cohabitation. And even now, 100 years after her birth, to describe Lispector’s writing as political would surprise some readers.

I remember a conversation with a Brazilian poet who expressed his dislike of The Hour of the Star (1977), since he saw the work as a kind of ‘submission’ by Lispector to the criticism directed at her throughout the 1960s and 70s by a Left that saw her work as insufficiently ‘political’ in the context of the unfolding tragedy of the ‘years of lead’ of Brazil’s military dictatorship. However, what the writer seems to suggest in her book, as in others, is a lucid vision of a far older tragedy that did not conform to the narrow and dualist ideological notions of the time. The fact is, Lispector’s engagement in A hora da estrela differs at a fundamental level from that of the novels of the 1930s by Jorge Amado, Graciliano Ramos, José Lins do Rego and Rachel de Queiroz, and of those of the writer’s 1960s and 1970s contemporaries such as Antônio Callado and Ignácio de Loyola Brandão.

"Even now, 100 years after her birth, to describe Lispector’s writing as political would surprise some readers."

The silence of Macabéa is not the silence of Fabiano in Graciliano Ramos’ Vidas secas [Barren Lives] (1938); nor is it the stuttering of the landowning colonels of Jorge Amado’s Terras do Sem Fim [The Violent Land] (1943); similarly, there is something more atopic in the apparent innocence and dysfunctionality of Lispector’s protagonist than in that of a character such Capitão Vitorin in José Lins do Rego’s novel Fogo morto [Dead Fire] (1943), which is more utopian, or quixotic in nature. In his essay ‘“A vida oblíqua”: o hetairismo ontológico segundo G.H.’ [‘Oblique life’: ontological hetaerism according to G.H], Alexandre Nodari describes politicality in Clarice Lispector as ‘a species of politicality prior to politics, before politics, predating the city of men and of the subject (in law)’.

[...]

Share article