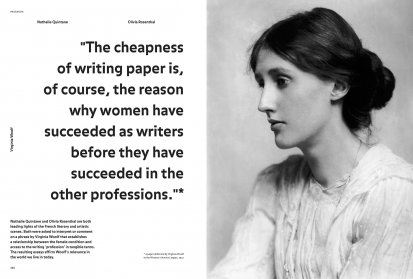

The other day, while out on my short daily walk designed to enable me to cope with working from home without a self-certificate or exemption form, my eyes drifted downwards as I thought of the prisoners who end up losing their sight as they are never able to look as far as the horizon. In solidarity with them, I stared at the edge of the pavement in front of me, and caught sight of an orange rectangle. I picked it up. To my surprise, it looked just like a €50 bank note. I was already rejoicing in this modest treasure when I noticed that it differed from the notes I was used to; it was decorated with a female figure – not an allegory of the Republic, Fertility or Justice, half-naked and wearing a Roman tunic, like most of the female figures on bank notes, but a portrait showing a real face that might have once belonged to a real woman whose actions, writing or words justified her appearance on a bank note, just as the old franc notes once showed Corneille, Pascal and Voltaire in an attempt to remind us of our country’s literary prowess.

I didn’t know who the woman was. I assumed it was a fake (because who would ever put a woman on a bank note?), and I decided to check straightaway by testing its exchange value at one of the so-called essential businesses still permitted to function. I headed to the first bookshop I came across, where a table with a sign saying ‘click and collect’ blocked the doorway. The bookseller told me I could have a quick look around to find what I wanted, and then he would ask me for the titles I wished to buy and bring the books to me. The idea of having to say the names without taking the opportunity to wander the shop’s aisles left me speechless for a moment – I’m used to rambling around, picking up a book, taking another, scanning a back cover, dawdling until I’m certain (even if I’m later disappointed) that the book in question will give me a stimulating, different, surprising perspective on something I’ve never considered: a book capable of changing my way of seeing things and perhaps even my way of life (we often overestimate books’ ability to emancipate).

Knowing I had to be quick, I was drawn towards two books that, judging by the blurb and recommendations on their covers, seemed worth reading. When I returned to the counter, I told the bookseller the names of the authors and put the bank note down in front of him. He looked at it, glancing suspiciously at me. I feigned indifference, so he picked up the bank note, flicked it between his fingers, turned it over and over, held it up to the light, felt its watermark, and typed something into his computer to check the apparently recent existence of the bank note (it had no doubt been released during the latest lockdown, when everyone was too distracted by the pandemic to notice the introduction of this currency with a female face, avoiding discord and a flare-up of violent reaction against the supposedly divisive feminists behind this inauspicious initiative that could result in public burnings and the withdrawal of the offending object). He nodded, doubtfully. Yes, the bank note was real and it could now be used in place of the old notes. However, the disgust on his face suggested that he was far from convinced by this new development in the world of finance. After checking the prices of the two books I had requested (€50 in total), he agreed to accept my note on the condition that I added another €10 note in the old format. I protested. He said, very seriously, that a €50 note with a woman’s face was worth 20% less than the same note showing a man’s portrait. ‘But why?’ I protested, wearied and increasingly annoyed. ‘Because women earn 20% less than men’, he said, undeterred, ‘so they’re worth 20% less than them. [...] The other solution’, he said, ‘is for you to swap these two books written by men for two books written by women’. I was dumbstruck and searching for words when the bookseller, an otherwise amiable man, pressed home his advantage: ‘You want to pay with Monopoly money, so buy books by women’, he said, smiling.

(...)

Share article