Of all the remaining vestiges of the Portuguese World Exhibition, one collection stands out above all others: the countless photos representing and reproducing it. These compelling records have the intrinsic tension of historic cultural artefacts brought up to date by the jaded gaze of the present. Their ‘interpretive power’ (Benjamin 2015) prompts a voluntary effort to reconfigure them as a temporal sequence, endowing them with spatial continuity and political vitality. They insist in presenting themselves as aesthetic objects captured in separate shots, with no connection whatsoever between them.

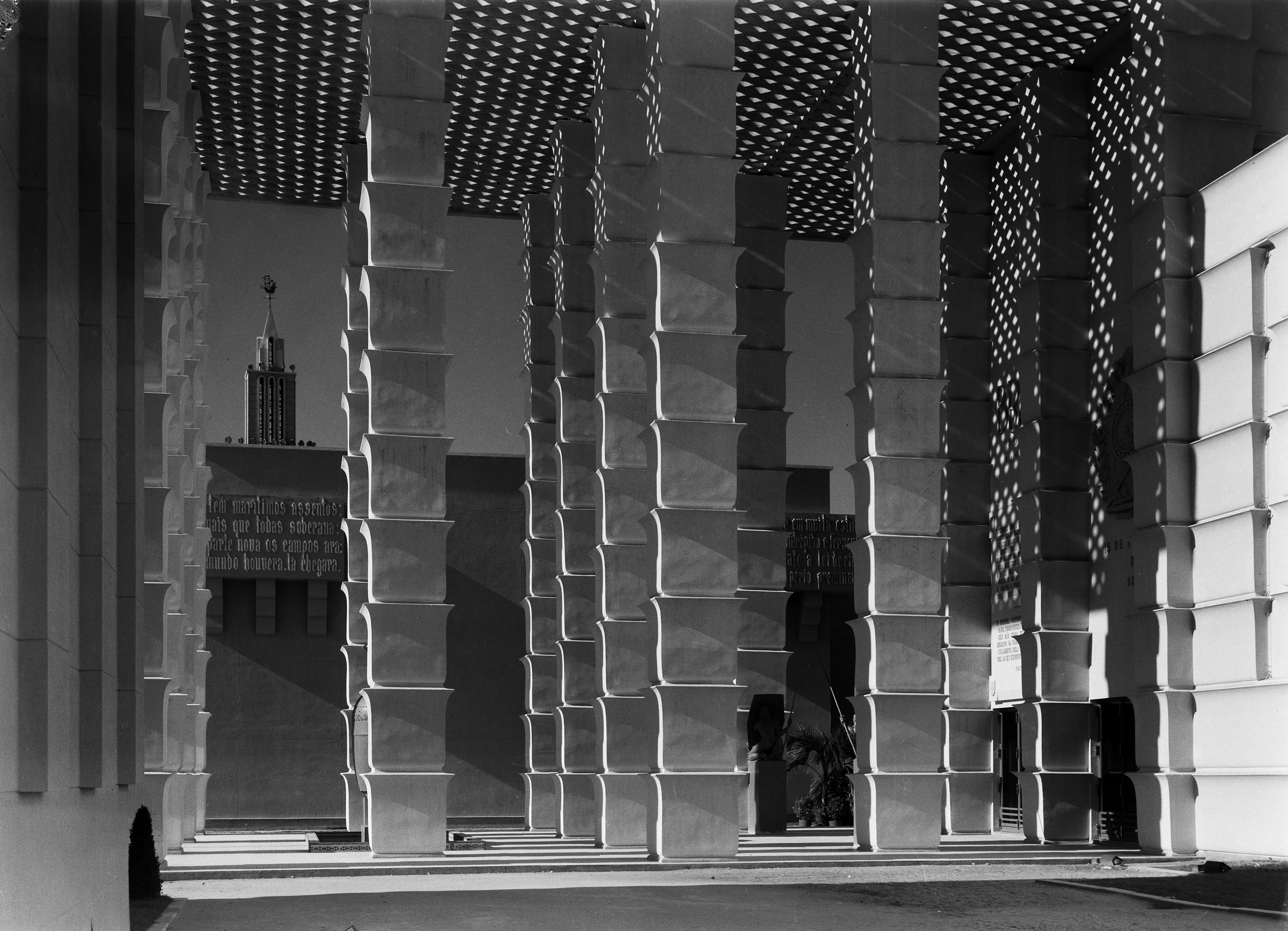

I walk through the entrance of four gigantic blocks, four medieval sentinels, whose magnitude and gravity retain the power of attraction of all things immense almost intact. The demonstration of power is undiminished, but the use of aesthetic persuasion is perturbing. The photos have only one purpose: to turn a declaration of authority into an attempt at seduction. I force myself to define them as illustrations and emblems, an expression of the declarative effort to create an apologetic narrative for the New State’s authoritarian nationalism and imperial project. This is because memory is not inert; it destroys, conserves and transfigures, and what remains in the modern day is a political battleground where forgetfulness and memories are toyed with, and often for premeditated and provocative reasons.

To each photographed line, volume, ornament and symbol narrating the nation’s grandeur, the eloquence of its empire, and the virtuosity of its benevolent colonialism, should also be added the goal of the organisers of the Portuguese World Exhibition held in Lisbon from 23 June to 2 December 1940: to impose a legitimising ideology on the usurpation of political power by an elite that sought the exclusive right to decide the national interest.

Planned as part of the programme for the Double National Centenary (the founding of the nation in 1140 and the restoration of independence in 1640),the Portuguese World Exhibition should be understood in the context of this eminently discursive meta-event, filled with symbolic rules and put in the hands of professionals of dissemination, a variety of politicians, priests and journalists. For three years, from the moment the celebrations were announced until their completion (1938–40), their job was to express the providential meaning of Salazar’s authoritarian nationalism by repeatedly conveying the nation’s inevitable and indisputable purpose. As António Ferro exhorted: ‘Children will finally and instinctively realise that they were born in a better Portugal and will laugh more healthily and heartily’ (Diário Notícias, 17/06/1938). The self-defining narrative and ceremonial storyline, the script for the Double Centenary commemorations, was responsible for articulating the ideological content of the exhibition.

In March 1938, in an international context marked by the ascension of Fascist- inspired regimes and the domestic affirmation of a totalitarian project to re-educate the Portuguese people (Rosas 2013: 318), every newspaper and radio station reported the official announcement of the Double Centenary commemorations by Oliveira Salazar, the head of government. The new authoritarian regime, formalised only five years earlier, would ensure the initiative was the most important political and cultural event of the New State and would mobilise significant human and material resources to that end. The preparations coincided with the period of internal consolidation of the regime’s more ideologically militant support base, one of the most extreme periods of political repression (according to the statistics available, over 8,000 political prisoners were seized between 1937 and 1938, and most of those sent to the Tarrafal concentration camp on Santiago Island, Cape Verde, were held without trial). All ideological means were used, once their effectiveness and results had been confirmed. Suffice it to recall the myth of the empire recreated in the Colonial Exhibition (1934), the insistent affirmation of the essence of Portuguese Catholicism manifested in the crosses displayed in every classroom (1936), and the construction of the myth of the purity of rural life, evident in the competition to name the nation’s most ‘Portuguese’ village (1938). Myriad bodies, many recently created, were recruited, such as the Department of Censorship [Direcção dos Serviços de Censura], the National Propaganda Bureau [Secretariado de Propaganda Nacional], guilds, national trade unions, the Portuguese Youth Association [Mocidade Portuguesa], the Portuguese Legion and the Mothers for National Education [Obra das Mães pela Educação Nacional]. Others were rehabilitated, such as the Ministry for Education, the Catholic Church, press organisations, radio channels, museums and academies.

Share article