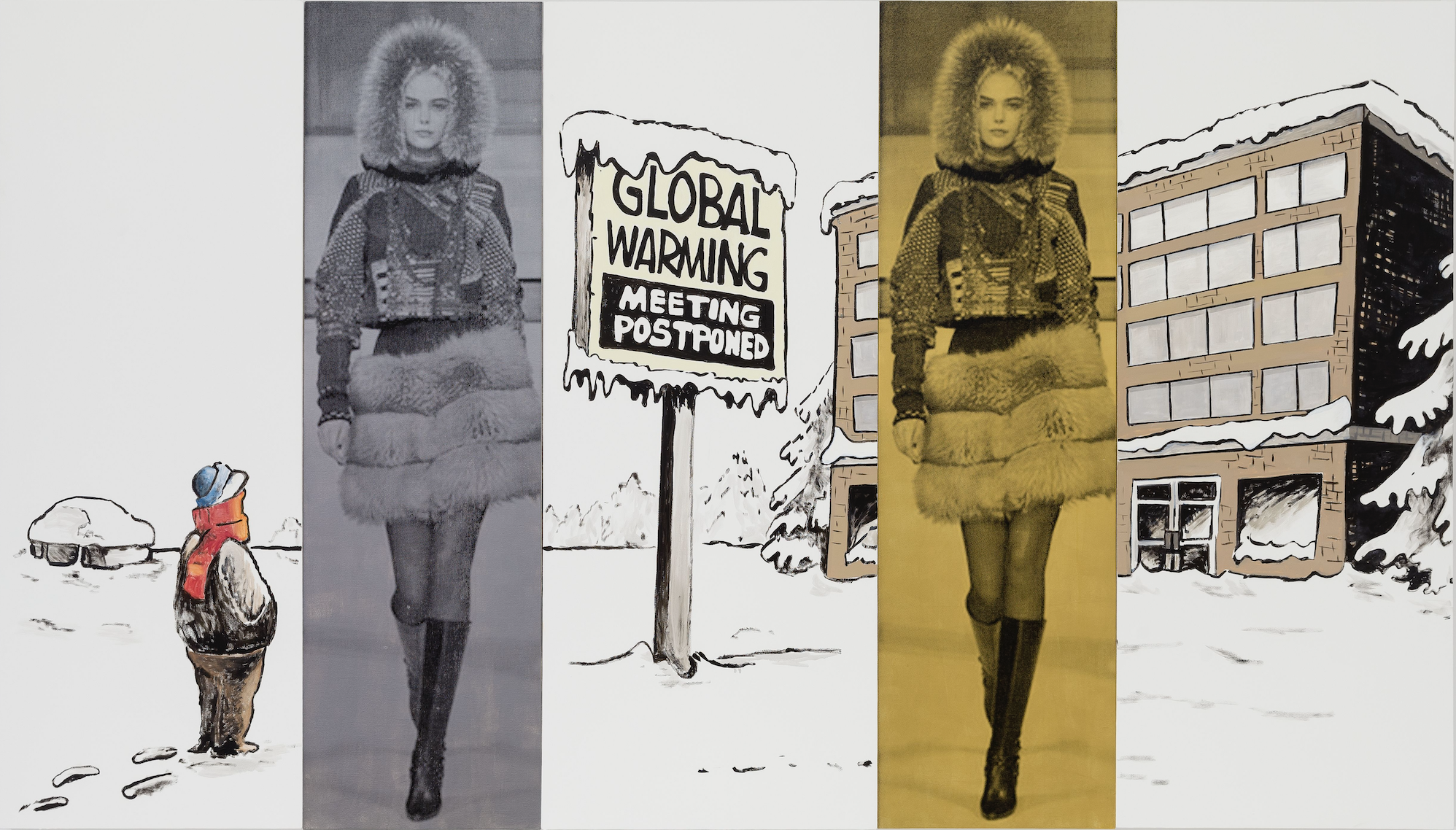

By the beginning of the modern age, celebrating the fame of a human being or a god seemed to have become impossible. This is made evident in Hölderlin’s last hymnal fragments, in which eulogies and praise shatter and split into unrelated, paratactic phrases, as though a deep, visceral fracture prevented the full development and celebration of memory. The same difficulty is described, with a disillusioned tone, in one of Leopardi’s Operette Morali [Small Moral Works]: ‘Parini on Glory’. This addresses the fame of writers, philosophers and poets, but its observations remain relevant today, if we substitute the word ‘spectator’, for Leopardi’s word ‘reader’: in the modern world the public prefers ‘fervour to modesty… mediocrity to perfection’, but above all – and this refers to the prevalence of the imaginary over the actual – ‘the apparent to the real’.1 In big cities the situation is worse, because even in Leopardi’s time these were the places that saw the emergence of such aimless, frantic movement; the restlessness as an end in itself which would become the subject of Simmel’s analyses, and which prevents opinion taking shape around the qualitative value of a human being and a work – that is to say, a movement that reduces fame to a phenomenon of fashion. Leopardi notes ‘the riot of these places, and the sight of the tinselled splendour’,2 and then recalls the shallowness and the vacuous shifts from one belief to another. We are dominated by distractions, as he terms them, and frivolous gossip. This comes from the supremacy of the imaginary, from the fact that we allow ‘our imagination’ to prevail rather than ‘the inherent qualities of the things that please us’.3 Hence, fame is a phenomenon that ‘may be compared to a shadow which you can neither feel when you hold, nor yet keep from fleeing away’.4

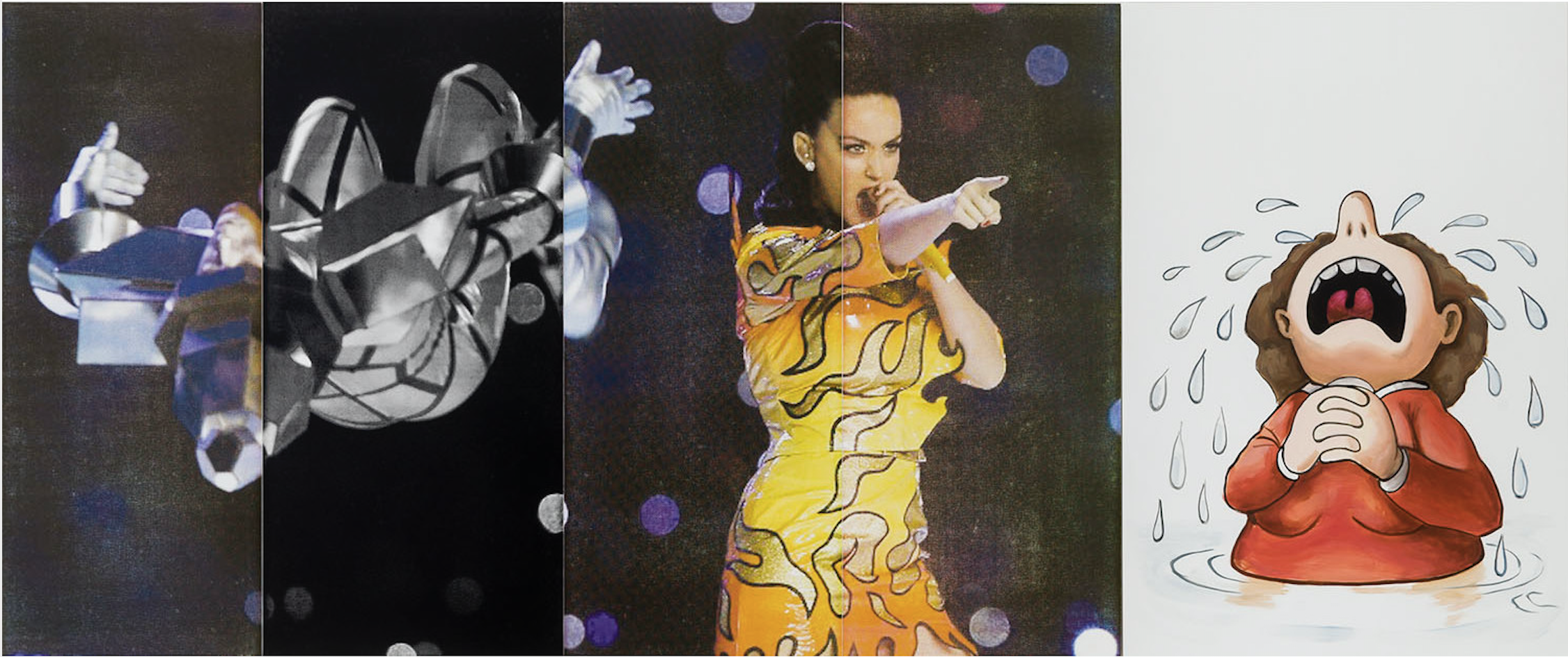

In the society of the spectacle described by Debord, fame is bestowed on those who have best succeeded in giving an affirmative appearance to material vanity. The glory that attaches to the spectacle’s well-known characters no longer resides predominantly in their specific activity, but in a form of appearance that they all have in common and that transforms them into stars. Whether or not they are writers, politicians, dancers, street fighters or doctors has little importance, so long as they are conspicuous and present themselves in the uniform way that the spectacle demands: ‘As specialists of apparent life, stars serve as superficial objects that people can identify with in order to compensate for the fragmented productive specializations that they actually live.’5 Apparent life is a substitute for actual life, and stars specialise in appearances. Their virtuosity consists in their constant existence in the realm of the possible, in endless mutation, creating the utopian illusion that everything is granted to those who accept the rules of the show (no matter whether they are heroes, politicians, ham actors, dancers, popes or footballers). They inhabit a domain of bustling, empty euphoria, a state of permanent exhilaration within a state of permanent distraction: ‘The stars of consumption, though outwardly representing different personality types, actually show each of these types enjoying equal access to, and deriving equal happiness from, the entire realm of consumption.’6

In the emergency situation created by the recent pandemic, have we not seen scientists performing on talk shows with the same narcissism as politicians and second-rate actors? The basic rule that determines a star’s fame in the society of the spectacle can be articulated as follows: the more that intellectual vocation and professional activity become devalued in reality, the more their spectacular performance offers a seductive and powerful surrogate. This is a consequence of the most deep-rooted characteristic of this form of life: the more a phenomenon loses in terms of material quality, the more its image-phantasm acquires splendour and glitter; the more artificial it is, the more it must appear natural and plausible; the more it is the result of economic necessity, the more it appears to be delegated to individual free choice.

Share article