On presenting the feature section we have called ‘In These Great Times’, we must highlight some of the topics chosen, as they refer to phenomena and ideas that are characteristic of our times. However, we must also question the very notion of ‘times’ (or ‘epoch’), its precision and its distinctiveness in an age obsessed with all things contemporary but unable to give contemporaneity a precise content or some chronological boundaries.

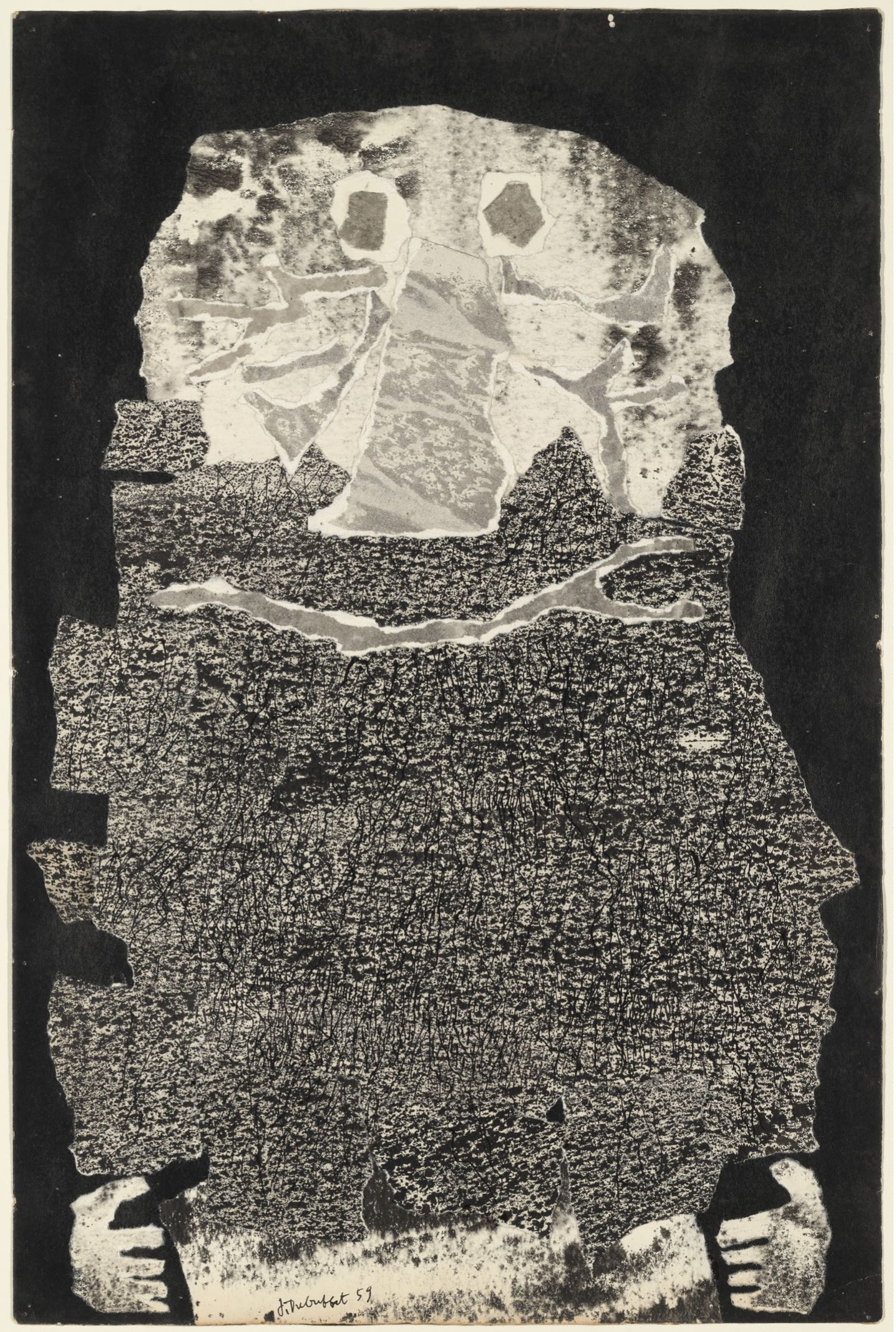

‘In these great times, which I have known since they were this small; which shall become so again, if they are given time enough for it […]’. These are the first words of a particularly virulent libel with which Karl Kraus whipped up his age and the political and cultural life of Vienna — a ‘weather station’, he said, that captured the signs of the ‘end of the world’. The year was 1914. Kraus was keeping alive, almost by himself, the incendiary flame of his magazine Die Fackel, where he published this article titled ‘In these great times’ (‘In dieser grossen Zeit’). Its apocalyptic tone was shared and wildly cultivated in almost all the ‘diagnoses of the times’, a type of essay that produced quite a body of literature in the early decades of the twentieth century.

By summoning up Karl Kraus’ text (or rather, its initial words) to name the Subject in this first issue of Electra, we do not intend to restore the apocalyptic tone, nor claim as an authority that view on world history, which makes the notion of ‘epoch’ a fundamental methodological instrument. Surely, the word ‘end’ returned to haunt our times. Postmodernity was the name given to the end of the modernist ‘grand narrative’. The so-called ‘postmodern discourse’ sought to make a new historical period intelligible, a period that came after the end and could only be termed ‘post’: hence post-ideological, post-utopian, post-historical, etc. The paper on post-democracy written by Roberto Esposito for this feature section, refers to the more recent state of affairs when liberal democracy — once considered inherent to the global triumph of capitalism — entered a stage of fatigue, or regression. Since the beginning of the century, the very notion of ‘post-modernity’ has lost the radiance that once caused it to be the name of the age in which we live, our present times.

The reasons are manifold and have been the subject of an ongoing discussion. One of the main theorists of post-modernity, the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, author of La condition postmoderne (1979), stated, some years later, that to consider the prefix ‘post’ in the term ‘post-modern’ in the sense of a mere succession, the diachrony of identifiable historical periods, was the continuation of a totally modern logic of thought. This clearly shows the concept’s lack of clarity, since it served both to understand Fukuyama’s announcement of the ‘end of history’ (whose resonance was eminently post-modern), and to characterize urban fashion and lifestyle trends. More generally, the announcement of the end of the great emancipation narratives created the idea of an end to politics and an end to conflict, which were ultimately reignited in other ways.

Meanwhile, words such as ‘biopolitics’ (also referred by Roberto Esposito), ‘neoliberalism’ (especially applied to the Reagan / Thatcher era), and ‘populism’ dominated the discourse of political theory and the ‘profane’ public space of the media. By and large, regression became a topic; or even ‘great regression’, as in the title of a collective book published in Germany in 2017, and then in other European countries, which calls to mind a recurrent theme: our times are showing some of the distinctive signs of the late 1920s and 1930s. What was called ‘regressive modernization’ — a characteristic of our age — has some equivalence to the ‘conservative revolution’ that preceded World War II, to the point that we are talking today of ‘de-civilization’ (to evoke Norbert Elias). In the early decades of the twentieth century, the German ‘conservative revolution’ pitted civilization against Kultur, as shown by Thomas Mann in Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man. Overall, a global shift to the right, even to the far-right, has become evident, so much so that this very perceptible movement has already been called the world’s shift to the right.

The philosophies of decadence and the apocalypses of Kraus’ age have become much less ‘spiritual’, and the term nowadays denotes something that is not associated with philosophies of history or theological categories. It refers, brutally, to the idea of the extinction and self-destruction of mankind. The notion of catastrophe is commonly associated with natural disasters, but such disasters are recurrent nowadays, and not natural at all. Ecological catastrophes are the consequence of man’s continued action on the planet, accelerated by the ‘fossil economy’ that began with the Industrial Revolution and has been growing exponentially. The idea that we have already entered a new geological era, the Anthropocene, appears to be very plausible. This is the great topic of our times, addressed here by Frédéric Neyrat, a French philosopher at the forefront of the debate on issues of political ecology. His books Biopolitique des catastrophes (2008) and La part inconstructible de la terre: Critique du géo-constructivisme (2016) are fundamental in this debate. Our great age continues to gloss the apocalyptic theme of bygone days, but now sub specie ecological — as shown in Há Mundo por Vir? Ensaio Sobre os Medos e os Fins, a book by the Brazilian philosopher Déborah Danowski and the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, whose interview to the Italian philosopher Andrea Cavalletti is another feature in this issue of Electra.

The reference to Karl Kraus comes from the conviction that his words have reached our present time with his critical and analytical power intact. They serve as an antidote to the total absence of thought that is implicit in an ideology, disguised as realism, which tells us that things are what they are and we cannot but adhere to them uncritically. Karl Kraus’ satirical critique was based on the idea that it is possible to understand and characterize a ‘state of affairs’ in order to obtain that homogeneous entity which we call ‘our times’. We do realize that, when transposed to our age, the idea seems much less reasonable and convincing. Kraus and other writers and philosophers of his time applied themselves to gaze at the sphinx that confronted them — the embodiment of the epoch, an effective individuality of historical progress, endowed with a ‘spirit’ (the ‘spirit of the times’, or Zeitgeist) — equipped with conceptual tools that could identify and analyse the symptoms, and solve the enigmas of the sphinx. As the process considered culture, society, and even historical development as organs ravaged by disease, the ‘diagnoses of the times’ proliferated. Today we cannot be deluded into thinking that this medical-analytical practice is possible, because the object of diagnosis is no longer as conspicuous under the scrutiny of our theoretical tools. The specific aspects of an epochal situation have now become blurred; our age no longer has a uniform tone, nor a single and unique sound. A vision of history that is set in a succession of autonomous epochs has ended. Instead of diagnoses and figurative representations of an epoch, what we see today are attempts to establish maps of nomadic concepts and a lexicon that can guide us. We tried an exercise in mapping that lexicon at the end of this special feature, limiting ourselves to ten words. One of these words is ‘gender’, which, since it has become so dominant in contemporary discourses (not only in the fields of humanities and social sciences, but also in everyday communication), deserves more than an entry in a lexicon of the present times. Pê Feijó discusses gender issues at length in his feature piece. However, we could expand the map, and add entries such as Biopolitics, Future, the Internet, Multiculturalism, Politically correct, Populism, Precarity, Terrorism. We will certainly return to some of these words, since all of them are part of contemporary topics and debates that this journal will address.

Contrary to what has happened since the Age of Enlightenment, which was conscious of representing a new era in its pure state, we do not have a proper name for our times. Or rather, we have a cacophony of names. One name — perhaps the one that best illustrates the difficulty of diagnosing, and provides our great epoch with a figure that could give intelligible meaning and form to its manifestations — sounds like a tautology: ‘epoch-making times’ (we owe it to the philosopher Odo Marquard). What does it mean? It means that today there is an acceleration of time that leads to the identification of shorter historical units, in such a way that in our time nothing sediments because it immediately becomes the past. These are ‘interesting times’, as Slavoj Zizek said — and, before him, the historian Eric Hobsbawn. These are times when it is impossible that a literary work could be deeply rooted in its age, as were the great modernist novels — James Joyce’s Ulysses, for example, of which Hermann Broch said it had the capacity to apprehend the concrete totality of ‘universal daily life of the age’, giving it form and expression.

Ultimately, we must take a critical look at the very notion of epoch, because it no longer corresponds to the perception of an intelligible temporal unit. ‘The time is out of joint’. These words from Hamlet acquire a new resonance today. ‘Epoch’, let us not forget, comes from the Greek word epokhê, the same word that is used in philosophy to name the suspension of judgment and simultaneously means a period of time, an era, an age, but also an interruption. The epoch of epoch-making, paradoxically, has some affinity with an idea from Bernard Stiegler: we live in the epoch of the absence of epochs. It seems to be a very abstract formulation, the very words from the theory that compels us to gaze at the stars and run the risk, like Thales of Miletus, of falling into the well because we do not look where we are going. But the truth is that Stiegler got the concept from the testimony of a young Frenchman, Florian, for a collective book. Let us quote it, because, in our great times, it is difficult and painful to make the words of a 15-year-old perfectly audible: ‘You really take no account of what happens to us. When I talk to young people of my generation, those within two or three years of my own age, they all say the same thing: we no longer have the dream of starting a family, of having children, or a trade, or ideals, as you yourselves did when you were teenagers. All that is over and done with, because we’re sure that we will be the last generation, or one of the last, before the end’.

Share article