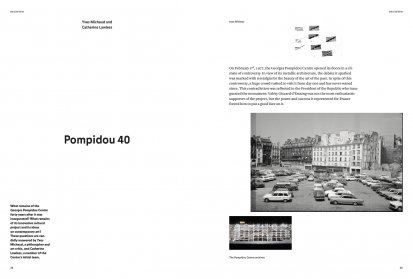

The architecture of the Pompidou Centre, so denigrated at the time, was representative of an industrial and cultural revolution. The world had changed, artists’ studios had become factories, design was breaking out of the confines of industrial plants, abundant fuel had revolutionised the way people circulated around the world — a movement that transformed lifestyles was gathering momentum. And this is the movement reflected in the architecture of the Pompidou Centre.

This building, as its architects have said, is not a building, but a moving engine, one that is scalable and flexible — it is a living tool. In theory, it can be disassembled or expanded. Its mandate is to show the force and originality of the twentieth century expressed in film, television, computers, spacecraft, in order to connect them to art and create a dialogue among them, since this is the expressive context shared by artists from all the disciplines. The transparency of the facade invited members of the public outside into a dialogue with those inside the Centre, to which admission was free — especially the entrance lobby, called the Forum, which was originally designed as a passageway between two streets, the Rue du Renard and the Rue Quincampoix. When you crossed this Forum, intended as a covered square extending the Centre’s exterior square, you walked into a ‘centre in the centre,’ where all the branches of the Centre’s many departments could be found. This meant that a pedestrian crossing the square could make a detour through an exhibition gallery or read a review along the way. We will come back to this, because today this forum has become a cultural shopping centre, the institution’s cash cow.

The escalator that runs across the entire facade, and which visitors have to take in order to access the various inside spaces, frees the interior of a large number of lifts while also serving as ‘a climbing street’ — the people on the moving staircase create a human fresco, infusing it with life. The public was meant to be part of the architecture and its movement. The escalator also offered one of the most beautiful views of Paris and suggested a link between the past and the present, which awaited visitors inside.

The arrangement of the Centre’s spaces was intended to express its cultural policy. The apparent complexity reflected that of a city and its mysteries. The idea was to reproduce the streets, a square, and houses, so that the encounter with art would be as unexpected and familiar as an encounter in the city. But, as in every city, maps and plans also allow people to take their bearings, and give meaning and an identity to each neighbourhood.

Two movements flowed at a different pace.

The temporary shows took place in the ‘common’ spaces: the basement, the main lobby, the ground floor, and the fifth floor. The works exhibited in the Musée nationale d'art moderne (MNAM), located on the third and fourth floors, and those in the Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI), located on the first and second floors, formed part of the permanent collections.

The Centre presented itself as a Ferris wheel of exhibitions and temporary shows that rotated around a fixed space, whose two hearts are the museum and the library.

The unity, strength, and novelty of the Centre lay in how these two movements met up, in the confluence of the common spaces, which were designed to invite the public to come back often and discover something new each time. Entrance to these spaces was always free, whether to take in contemporary art and architecture shows, read books, visit the children’s workshop and library, view the monumental exhibits in the Forum, or attend concerts, dance performances, conferences, or debates in the basement.

On the fifth floor, there were the major exhibitions that made history, like the cycle of shows conceived by Pontus Hultén, Paris‑Berlin, Paris-Moscow, Paris-New York, and Paris-Paris. Life at the heart of the Centre (the museum and the library) went on at a different pace, with a more inward, limited rhythm, as if punctuating the spiral that surrounded it.

This principle guaranteed the huge success of the Pompidou Centre from the moment it opened its doors. The public discovered the joy of being able to move around in the midst of this hive of artistic expressions, which were meant to be discovered or compared with the old masters — because the route around the museum began with the Impressionists and the Fauvists, which linked up with the latest pieces in the Musée d’Orsay collections, and continued up until today.

So how did the Pompidou Centre evolve?

When it opened, the scenography of the collections, the themes of the major temporary exhibitions on the fifth floor, and the exhibitions in the Forum and the mezzanine were all innovative with respect to academic criteria.

The presentation of the permanent collections at the opening of the Pompidou Centre was based on a museological principle common to all its spaces, whether they housed works of art or documents. The key words were mobility, flexibility, transparency, freedom of movement, a gateway to the city, and so forth. The principle was to encourage a panorama view of various works by different artists of the same period, in order to stimulate learning about the artistic scene while at the same time showing differences, variations, and connections between them. So the moment you walked in, works by Rousseau, Matisse, Picasso, Léger, Braque, and Bonnard were all to be discovered in the same field of view. As the Centre’s first director, Pontus Hultén, once said, ‘The proposed layout was a guiding thread for visitors to follow, taking its inspiration from the form of cities, with squares, streets, and dead-end alleys, and acknowledging the alternation of motivation, interest and even fatigue.’

On the third floor, paintings by the Fauvists led to Chagall, whose works were on the fourth floor, all the way to the post-World War II works of Matisse, Léger and Picasso, and then, separated by a fire wall, came contemporary French and international art. The whole labyrinthine layout was meant to suggest a history of art woven with multiple relations.

In the early days, the fifth floor hosted the large-scale, multidisciplinary exhibitions Paris-New York, Paris-Berlin, Paris-Moscow, Paris-Paris, once again with the idea of a multiple history; this time mixing up the artists’ works with design, posters, literature, music, and so on. They created large frescoes of the history of art in the twentieth century, which shared their space with the monographic exhibitions on prominent artists of the twentieth century, such as Marcel Duchamp, Kazimir Malevich, Dalí, and Magritte.

In the Forum, at the centre of the Centre, a pit provided a place for monumental works to be displayed, always on a temporary basis. There was the Crocrodrome created by Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Bernard Luginbuhl, as well as Daniel Spoerri’s La Boutique aberrante. These were followed by Dalí’s mural decorations for the World Exhibition, Picasso’s backdrop project for Le Train bleu, three musical totems by Takis, an immersive video environment by Nam Jun Paik, and sculptures by Alexander Calder, among others. The ‘environment’ as a work of art was the first thing visitors experienced. The visual shock they received when coming into the Centre set the tone of the venue they were entering.

Not that this stopped them from exploring the surrounding spaces, which, while more modest, were no less innovative. The ‘Artist’s Studio’ was a room dedicated to a different young artist each month. Spaces like the Galeries contemporaines, the Salle Animation, the Salon Photo, and the forum gallery presented the latest concepts in the art world, whether in cinema, photography, or fine art by major artists from France and from around the world.

The Museum’s programming ran alongside the exhibition hall of the Centre de Création Industrielle (contemporary architecture, design, and furniture). But it also rubbed shoulders with the Salle d’Actualité in the public library, which gave free access to newspapers from around the world and a selection of books, and to the children’s workshops and a room for discussions and conferences.

Forty years later, what remains of this profusion, this freedom of movement, this transdisciplinarity that led to the worldwide success of the Pompidou Centre?

Like anywhere else, but more often in France than elsewhere, the Centre has become institutionalized, closed off, and centralised. Its Forum now resembles, more than anything else, a cultural shopping centre.

The monumental works, the artist’s studios, the Salon photo, the perennially crowded Salle d'actualité, the children’s workshop are no more. The pit is empty. An elevator has been installed in it, to go down to the lower floor. Free admission to the entrance lobby is also a thing of the past. All that remains are ticket counters, a large café on the mezzanine, a bookstore, a boutique selling objects of all kinds — from colouring books based on Matisse’s works to salad bowls or teapots signed by fashionable designers — terminals for buying tickets to the Museum and to the exhibitions, and queues to the all-in-one ticket windows.

In a word, this Forum, which was designed as a space for freely exploring the various activities of the Centre — the library, the museum, the Centre for Industrial Design, the Centre for Musical Research — has become a venue to open up your purse strings. Taking the escalators up to the fifth floor, where you used to be able to admire the view of Paris from a beautiful terrace, is no longer possible without an entrance ticket. In its place, a luxurious restaurant called Georges, after President Pompidou’s first name, has been installed.

The wheel-shaped movement that framed the museum and the library has been jammed and no longer turns so roundly or so widely.

Financial demands certainly have their weight: profitability is paramount today. Other critical factors cannot be forgotten: security problems have become increasingly important and have led to severe limitations on the freedom of circulation. The spirit of post-1968 has also faded away — now what we need is cleanliness and control. True, the entrance square to the Centre was gradually becoming a sort of ‘court of miracles’: a gathering place for beggars and street people. And then, of course, the management teams no longer have the enthusiasm or competence they had at the beginning. The recent heads of the Centre, often appointed as a reward for political services, are technocrats rather than people dedicated to the arts. The exhibition curators and commissioners come from politically correct backgrounds and lack the imagination of the ‘founding fathers’. There is also the fact that the world of art and culture have changed profoundly, and have ‘merchandised’ themselves to extremes.

The presentation of the collections, too, has become subdued.

Share article