Brazil is the land of the future, wrote Stefan Zweig, in 1939. With a less optimistic outlook, Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro argue that the future of the Earth — built upon inequality, ecological disasters, uncontrollable migrations, and disseminated poverty — will eventually resemble contemporary Brazil.

Author of essays on Leibniz and Hume, Déborah Danowski currently teaches philosophy at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. Viveiros de Castro, a theorist of ‘multinaturalism’ and ‘Amerindian perspectivism’ is one of the most influential anthropologists in the world; he currently teaches at the University of Rio and has lectured at the University of Cambridge, University of Chicago, and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris. They are both very active on environmental issues, and have fused their commitment with a theoretical tension that is rooted in the book entitled Há mundo por vir? Ensaio sobre os medos e os fins (2014), of which they are co-authors. This innovative and profoundly insightful work, greatly admired by Bruno Latour, addresses the most pressing and troubling theme of our times, which we refer to by the term used by Nobel Prize winner Paul Crutzen: the Anthropocene, the era of terrifying environmental changes produced by humankind.

Of course, Danowski and Viveiros de Castro do not labour under any illusion: we are at the end of times. Equipped with a strong theoretical apparatus that combines Gunter Anders’ ‘principle of despair’ with the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari (and the Deleuzian reading of Gabriel Tarde’s universal sociomorphism), the theories of Isabelle Stengers as well as those of Donna Haraway, they shed a radiant light upon the end of times and upon these accumulative discourses. Their illuminating analysis is based on scientifically correct and alarming data, but it also inspires the imagination and examines our apocalyptic visions, whether printed on the pages of Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, or projected onto the screen in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia or Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky’s The Turin Horse (A torinói ló). The theory of Perspectivism is entrusted with a decisive function. Some of the finest pages of Viveiros de Castro’s work (from The Inconstancy of the Indian Soul1 to Cannibal Metaphysics2) resound with a very explicit political tone. As for the Amerindians, their problems are a more pressing concern for us than we would perhaps suppose at first glance.

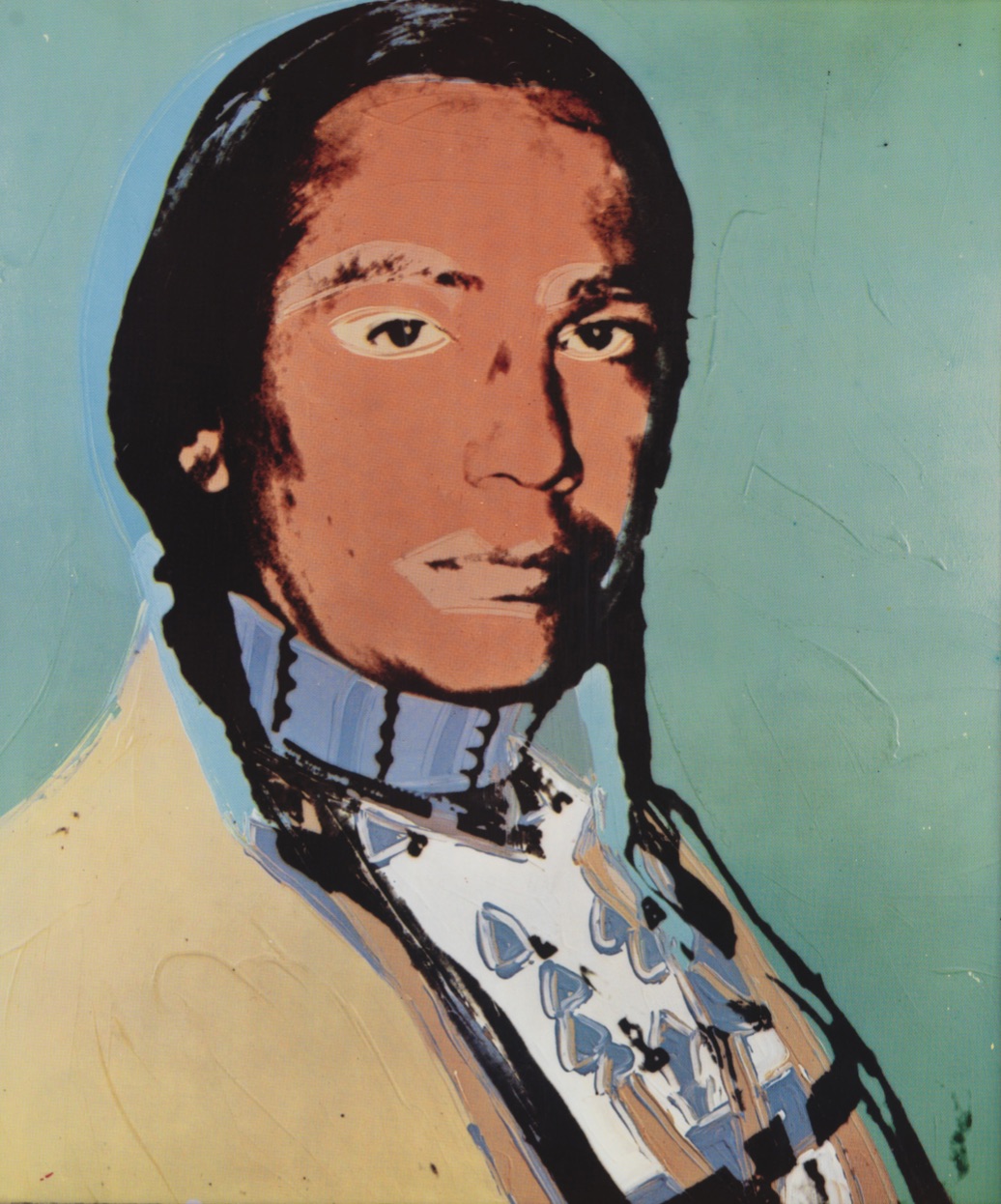

The end of our world, that is, the western capitalist world, as Danowski and Viveiros de Castro consistently observe, is not the end of all. And this is what the Amazonian peoples’ own testimony indicates: while they had been violently dispossessed of everything, slaughtered and reduced by the conquistadores to the state of a ‘humanity without a world’ (to borrow an expression from Günter Anders), they have nevertheless been able to resist — and they continue to resist — by inventing styles and sophisticated techniques of survival. In their myths, unlike our own, the end of the world does not coincide with the end of life. How could they do this? First and foremost, they have always been completely free of our dogmatic anthropocentrism and they live in the awareness of their own universal anthropomorphism. For the Amerindians, every being (the appearance of which is in our eyes either animal or human) has in fact a human soul. More specifically, each being views itself as human and views as human any other of the same species, while a being from another species is viewed as a prey animal. (So, we can be viewed as animals, and certainly appear to be animals from the point of view of a jaguar, but the jaguar views another jaguar as human). As they look at other living beings, the Amerindians know that the animals in front of them view themselves as humans, as Indians, and will reciprocate their gaze viewing the Amerindians (such as in the case of the big cats) as prey or (in the case of a weaker species) as powerful cannibal spirits. According to this inter-subjective notion, which is simultaneously complex and transparent, the other species is no longer human, and at the same time (‘within its own domain’) it is. Therefore, every interaction between species becomes an ‘international affair, a diplomatic negotiation, or a warfare strategy that must be conducted with extreme caution’. As a result of this, the Amerindians could never have believed in politics as a unilateral action on what surrounds them, nor conceive nature as a mere resource.

The Amerindians, who do not have a state and are not recognized as a people, think that everything is negotiation, everything is social, that each individual life is a true association of beings, and that politics and society do not concern the environment, but coincide in a sense with the environment itself. ‘They think that there are more societies in heaven and earth (…) than are dreamt of in our philosophy and anthropology. What we call environment is for them a society of societies, an international arena, a Cosmpoliteia. There is no absolute difference in status between society and the environment, as if the former were the “subject” and the latter the “object”. Every object is always another subject, and always more than one. The phrase “everything is political”, which is constantly on the tip of the tongue of the militant youth on the left, takes on a radical literal meaning for the Amerindians — something that not even the most enthusiastic protestors in the streets of Copenhagen, Rio, or Madrid would perhaps be prepared to admit.’

The Indigenous population, as Danowski and Viveiros de Castro claim, can be an inspirational example. Within our current situation, within the complicated, fleeting circumstances that are difficult to define, to live is (even for us) to survive, and to abandon the self-destructive and toxic habits of consumption we have grown accustomed to, in favour of a form of vital resistance. This implies first and foremost, a re-evaluation and a reality check: understanding the phenomena, fearing them, and even learning to accept and acknowledge all the fear we must feel in order to finally become completely aware of it. Moreover, it means applying the strength one gathers from this self-awareness on the ground, with no disregard for the spectacular constructed narratives and sermonizing, but understanding their effects and how they resonate, and taking into account ‘the impact coming from the steps of the Vatican relative to the public debates’ or from the appearance of An Eco-modernist Manifesto, ‘the leading document of the Breakthrough Institute’ which has been approved and signed by a variety of celebrated proto-capitalist contemporary thinkers, but which in actuality is not that dissimilar from the urge for vindication put forth by some of today’s prevailing Leninists. Even leftists (for example, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams with their Accelerationist Manifesto) claim that in order to survive the Anthropocene, we must ‘take advantage of every technological and scientific advance’ arising out of late capitalism. They think that in contrast to the ‘fetishisation of openness, horizontality, and inclusion of much of today’s radical left’, we must resort to ‘secrecy, verticality, and exclusion’ so as to accelerate ‘the process of technological evolution’, to ‘unleash latent productive forces’: as if any such advances will not actually end up reducing techniques to mere devices of exploitation (of humans just as much as nature), as if evolution was an indisputable value, as if production didn’t signify the destruction of the world, and finally, as if certain arguments had not even been ridiculed fifty years ago by the wisest Marxists (and the first of all, Jean Fallot).

To save us from our nefarious mythologies, while the globe reacts to our domination with the violence of an insane giant, the Amerindians come to meet us from the nearest future. This book, Há mundo por vir?, is the harbinger of their coming. And today we have the good fortune of engaging in a conversation with Danowski and Viveiros de Castro about this very book, and about this world that is lost but possible.

Share article