Boris Groys’s theoretical reflections in the field of aesthetics, media and the history of artistic movements and their institutions (especially the museum), from the avant-garde to modernism, have a strong international resonance, as we can gather from the dissemination of his books and the constant presence of his name in the various disciplines that his work touches on. In 1992, two years before he became a professor at Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design (which includes the ZKM – Zentrum für Kunst und Medien), where he had colleagues such as Peter Sloterdijk, Hans Belting and Peter Weibel, Boris Groys published a book ‘on the new’ (Über das Neue), described in its subtitle as an ‘essay of cultural economy’. We were at the height of the debate about the post-modern condition, prompted by the new cultural and political configurations of the time. The new seemed like a dated topic, given the disfavour into which the concepts of utopia, historical progress and authenticity had fallen. Gifted with an analytical sophistication that has only improved with time, Boris Groys focussed on discussing this paradoxical situation: no one believes in the new anymore, but everyone demands it. As the book’s subtitle indicates, this analysis established an equivalence between the cultural process and the economic process, but it went much further, showing that we can only talk about the new in relation to the archive (i.e. the old). Here we find the beginning of his later discussions on the museum and its function in contemporary society. This interview continues and revisits that essay on the new from 1992. We should note that it was precisely with an interview and a conference by Boris Groys at Tejo Power Station that we launched the first issue of Electra.

In this interview, eminent philosopher Boris Groys speaks on the topic of the new – a theme which he examined with great astuteness in his book Über das Neue. The interviewer, Catarina Pombo Nabais, is the author of the book Philosophical Conversations – Towards Self-Design, which is a long conversation with Groys.

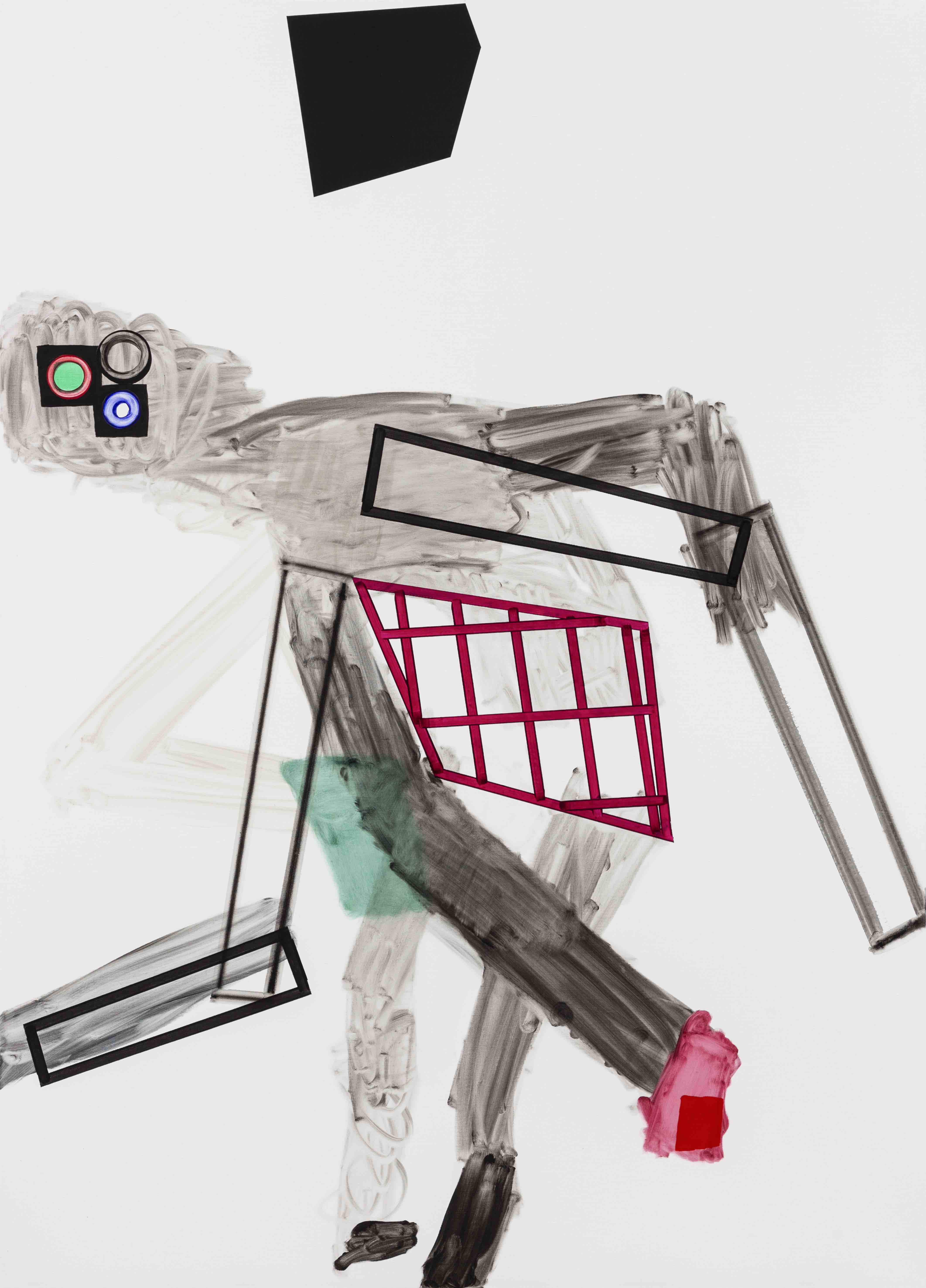

José Loureiro, Sinapse-morta Híbrido [Dead-synapse Hybrid], 2017 © Photo: Bruno Lopes

CATARINA POMBO NABAIS Let us begin by thinking about the impossibility of the new. Nothing new is possible is one of your main claims. What do you mean by that?

BORIS GROYS You know, when I wrote this book on the new1, I was teaching at the University of Texas. There, they have a special system of education in which everybody has to write some papers. And every time you do that, you are asked what is new in what you are proposing. Because if nothing is new, your work is rejected. So, the whole system seemed to me to be schizophrenic because, on the one hand, you say that there’s nothing new, and, on the other, you are required that every paper presents something new. And the same for the artists who should do something new. Musicians, painters, dancers, all artists should do something new. The requirement to produce the new remains as the most important requirement. This is the system there. So, the question for me was: why this feeling that there is nothing new? Of course, there cannot be any certitude that there is nothing new. In order to know that nothing is new, we would have to know all the future up to the Apocalypse and to the end of all time and then say that there is nothing new there. But we are not able to do so. So, from the standpoint of logic, this is a totally absurd statement. Thus, the question is: why has this requirement for a constant production of the new become possible? My answer is: because the past has been forgotten. Because we lost our culture, or we never knew it. And, since we forgot the past, we don’t know what is new and what is old because we don’t have any comparison. We cannot say that something is new if we are not comparing: these are old, these are new. But we don’t do this. For example, in the 1990s, I was teaching on the versicles. There was nobody among my students who had read the Bible. Nobody. I think they had not even read Shakespeare. So, for them, Dante, and the Bible, for example, were totally new because they were not at all informed about them. And, if somebody presented them with some of Dante’s poetry and said that it was new poetry, they would believe it. They would believe it because they don’t know Dante’s poetry. And of course, if one does not have this archive of cultural knowledge, one cannot say what is new and what is old. My suggestion is that we can speak about the new only in relation to the archive. (Not to the system, because the system is another question). If you do not have a certain archive, for example, museums, libraries, universities, we cannot say what is new. For example, for French Academy painters of the nineteenth century, the flat images from Japan or China were very new. Suddenly, these images without three-dimensional space were totally new. These images changed everything. It was the beginning of modernism. But of course, in China and Japan, people had always made such flat paintings, or flat art, or flat images. And for them, three-dimension illusion was new. Therefore, what is new for one culture can be old for another. In the beginning of the 1990s, capitalism was totally new for Eastern Europe, at least for Russia, because it hadn’t happened before. For me, when we speak about the new and the old, it is always an effect of comparison. It is a fact of comparison between what is already established as culture value, and what is not established as culture value. What is not established as culture value is new because it’s not included in the archive. But what is not included in the archive may have been made 10,000 years ago. Nowadays, people are beginning to include some paintings by Australian Aborigines that were made a thousand years ago in the cultural archive. But these paintings are new for our art system and for our archive. The idea of my book is that the relationship between new and old is a special relationship. It seems to be paradoxical because it is not a relationship of time, or a relationship in time. It is a relationship in space. What is within the archive is old. What is outside of the archive is new. Even if it was produced 10,000 years ago.

"The question is: why has this requirement for a constant production of the new become possible? My answer is: because the past has been forgotten."

José Loureiro, Reagente [Reagent], 2019 © Photo: Bruno Lopes

CPN You always have in mind the Western archive as the main central cultural reference. So, it’s a comparison between archives in only one culture. But, what about the comparison of archives between different cultures?

BG The position for every culture is between archive and profane. In China, for example, there is a kind of classical, academic tradition of painting and calligraphy, compared to which what comes from the West is profane. People look at that and they begin to ask themselves: how can I use this, what can I do with this, and so on. So, when I take as a reference my own archive, my own culture, for example the Chinese culture, then I ask myself: what can I take from a different, barbaric culture like Western culture, and use in my own archive? And if, instead, I emigrate and go to New York and live there as a Chinese, then my own culture becomes profane for me. So, instead of asking the question of how to include the elements of Western culture in the canon of Chinese painting, I begin to ask the question of how to include Chinese tradition in the Western canon? Everything is positioning, everything concerns one’s position in one’s own culture. When we emigrate or are very much confronted in our culture with migrants coming to the West, we see that they begin to use their own, original cultural identities as ready-mades to be included in the Western archives. The point is that an immigrant – and I was an immigrant when I wrote the book on the new – is a ready-made. His/her relationship to the institution is the relationship of a ready-made. Now, a ready-made may be interested, but may also not be interested, in being included in the Western archive. A lot of people are interested. Then, they try to integrate their cultural identity into the Western archives. But, for example, if you live in New York, you can go to Chinatown. There, you will see people who don’t speak English, or speak very bad English. They just live there. They are completely out of the archive and canon, which are totally irrelevant for them. The relation between the profane space and the institution is complicated. And one should also not forget when speaking about the system that the profane is always much more powerful than any institution or archive, because the institutions or archives are temporary. They will be destroyed. They were created and they will be destroyed. Actually, I think that museums, libraries and all the archives will be destroyed simply because there will not be enough money to keep them. There was a certain period when people began to build museums, libraries, universities. But now it is obvious that if you go to university, you don’t make money. You just lose, like, ten years of your life in which you could have made money. You are a loser from the beginning. And the same happens with recognition by the museum, which is incomparable with recognition by the market. The so-called intellectual recognition will all disappear. Therefore, in the relation between profane space and the archival institutional system, it is the profane space that always wins. Always.

[...]

[...]

Share article