Is it really possible to write a political history of football? What challenges will we have to face if we do? What boundaries must we draw in order to ensure that our political interpretation is accurate? How can we do it without contributing to the expansion of the political empire, which tends to crush everything that is not within its sphere of influence? And what can football teach us about the way we regard politics? In this article, I will endeavour to answer these questions in a tour of history that will take us from the first bicycle kick ever in the FIFA World Cup to Diego Armando Maradona’s famous ‘hand of God’.

Any political history of football is bound to be full of memorable events, geopolitical contingencies and ideological manifestations, and of names and personalities that have become cult figures, full of aspirations and world visions. This is the core of what the historian José Neves writes about.

FROM LEÔNIDAS DA SILVA TO DYNAMO MOSCOW

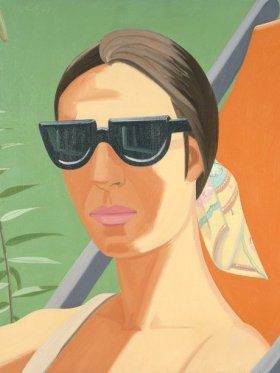

Brazilian Leônidas da Silva was one of the top footballers in the third FIFA World Cup, held in France in 1938. The journalists covering the tournament saw in him unique signs of a virtuoso, as exemplified by his bicycle kick. Other South American players have also claimed to be the first to use this acrobatic move and it is no coincidence that the bicycle kick is also known in the region as a ‘chilena’. Regardless of its origins, Leônidas’ bicycle kick at the 1938 World Cup was hailed as original in football by the international press at the time.

In Brazil, while Leônidas was being showered with praise, the sociologist Gilberto Freyre was extolling the virtues of the Brazilian team as a whole. Freyre upheld that every Brazilian footballer warranted attention and that Brazil’s football style ought to inspire joy and admiration in the rest of the world. He said that disenchantment with modern life in European societies, bogged down as they were in routine, would find redemption in a Dionysian Brazil that was not afraid to be happy, hated bureaucracy and was averse to the evils of industrialisation. It was a country that held out the promise of a wonderful future rooted in a multiracial past, in which Leônidas – still remembered as the Black Diamond – played a prominent role.

The Second World War clouded this sunny horizon, even though Brazil only joined the conflict some time after it broke out. The war changed social habits, labour practices and political relations just about all over the world – and also disrupted sports. Regional and national competitions were suspended, one of the reasons being the mobilisation of millions of young men. At an international level, the interregnum was even more conspicuous. The first FIFA World Cup had taken place in Uruguay in 1930, the year that marked the 100th anniversary of the country’s independence. The second was held in Italy in 1934 and the third in France in 1938, when the Brazilian team won third place. The tournament did not take place in 1942 or 1946. The fourth was held in Brazil in 1950 and the Uruguayan team won for the second time in its history.

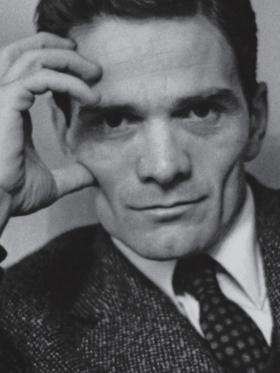

However, the love of football by no means diminished during the war. The international effects of the game did not disappear either. One symbolic, albeit minor incident is an illustration of both. Like so many others, young Eric Hobsbawm was called up for the war effort in Europe. Hobsbawm had a PhD in history and was a member of the British Communist Party. He served with the Corps of Royal Engineers during the war. From there he sent a football signed by a number of his fellow soldiers to the Soviet Embassy in London. The embassy was supposed to forward the ball to their comrades in the Russian engineer corps to express their solidarity in the fight against Nazi Germany.

"The first FIFA World Cup had taken place in Uruguay in 1930, the year that marked the 100th anniversary of the country’s independence. The second was held in Italy in 1934 and the third in France in 1938."

Curiously, as soon as peace returned and international matches began again, one of the first teams to play in the United Kingdom was Dynamo Moscow. The Russian team attracted large crowds to British stadiums in a tour that began in London in late 1945. It coincided with a return to some of the pre-war spending and appetite for entertainment. The tour was the target of considerable British media attention. This all happened at a time in football history when a newspaper review of the match or a commentary on the radio was not under threat of competition from television broadcasts, and was enjoyed by those who were unable to attend the game. At the same time, the country was celebrating the end of the war and the papers applauded the Soviet tour as it opened up new horizons for international cooperation and diplomacy based on recent memories of the alliance against Fascism and Nazism.

The Soviet players’ display of football skills in Britain surprised most spectators. It even became a subject for reflection and discussion. Their good results were hailed with sportsmanship by some newspapers, while they were regarded with suspicion by others. Some said that the teamwork in the Russian game with geometric, progressive passes was in line with traditional British football. But others attributed the intensity of this dynamic to the effect of control and discipline from above, imposed – if not insidiously indoctrinated – in the Soviet squad. The well-known journalist and manager George Allison argued that the skill of the Dynamo players should be downplayed, in that their performance was all down to a predetermined plan, without which the Soviets would be unable to play well, due to their lack of a sense of individuality.

The term totalitarianism would take hold as a concept years later for thinkers like Hannah Arendt, but it was already gaining ground in the informal philosophy that debates on football always involve. The Cold War had not yet begun, but the writing was already on the wall in Europe immediately after the war.

[...]

Share article