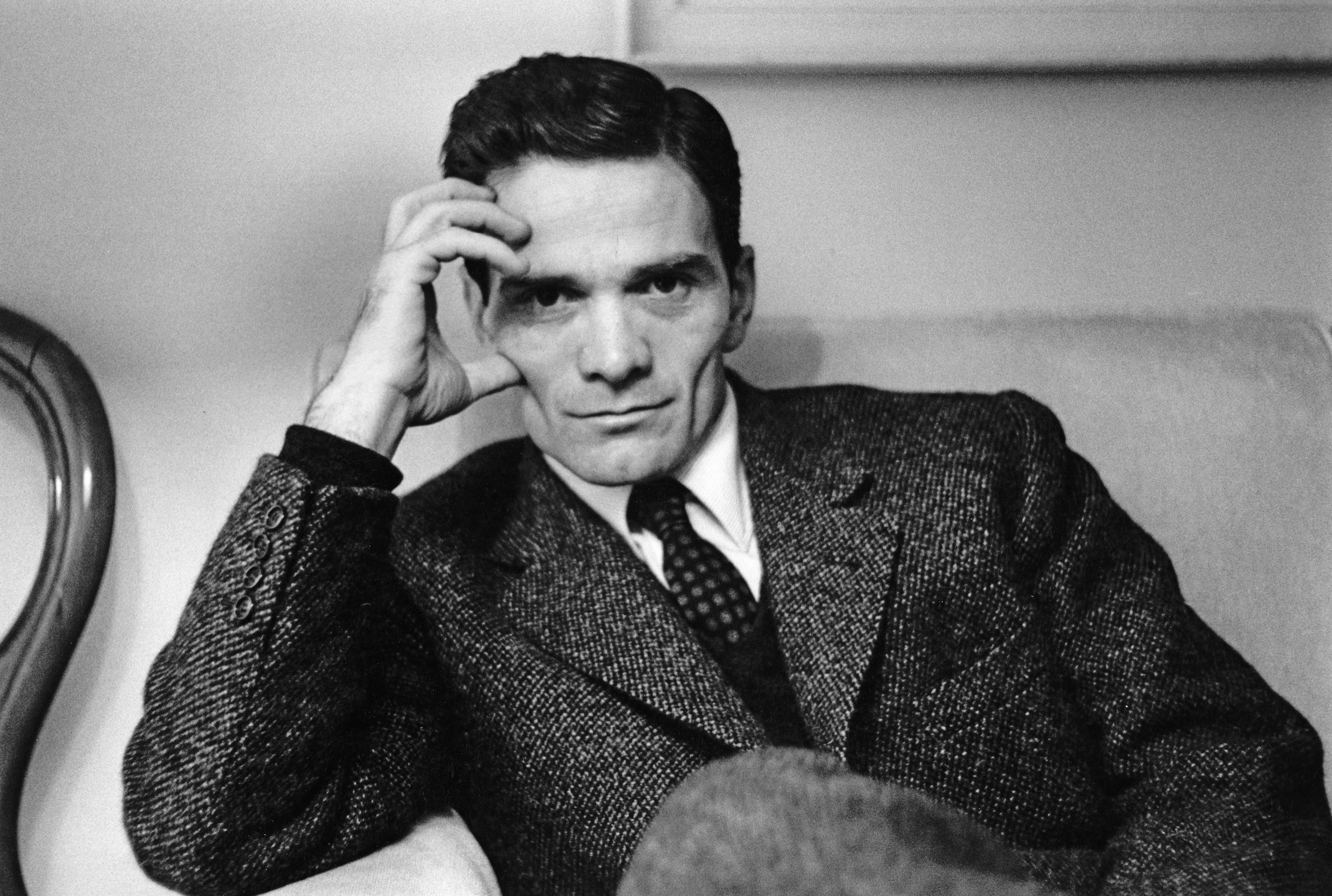

Pasolini was undoubtedly one of the most treasured artistic presences in twentieth century Italian culture. But that is not all: his work still speaks to us today, not only to academics but to many others, to the old and especially to the young, thanks to its emotional force. It is the artistic and ethical force of someone who has faced up to the evil of his own time and of ours, and who is therefore still able to stimulate aspirations and ideals today.

Pasolini was a poet, a novelist and a filmmaker: three artists in one. He reached the top in all these fields, to the extent that even if he had only expressed himself through one of them, he would still be equally remembered. If he had only made films such as Accattone, The Gospel according to Matthew, La Rabbia, Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom – to name only the most important, or at least the ones I like most – Pasolini would still be admired as a major figure in Italian cinema, alongside Rossellini and Fellini. And if he had only written poems, he would still be the great poet who made his debut when he was barely twenty with Poetry in Casarsa, and went on to write Gramsci’s Ashes, Poem in the Shape of a Rose, and Transhumanize and Organise. And the same could be said of his novels The Ragazzi, Amado mio and Petrolio, his last great experiment in the novel form, published posthumously since its author was killed before he could finish or publish it himself.

But there is also a fourth Pasolini, who broke out of the strictly aesthetic context to confront political and societal questions. He addressed the public at large from the pages of journals and newspapers with contributions that he himself described as ‘corsairs’, alluding to the thirteenth century maritime battles between Genoa and Venice, in which small, fast craft attacked the enemy’s powerful mercantile fleet. Pasolini took on equally mismatched challenges with his own small craft: his writing. His words had a personal and distinctive quality, always dictated by the need to say everything that had to be said, simply because it was the truth, even if it was inconvenient, even if it meant expressing views that were not those of the majority, or even if it involved telling truths that put his own life at risk.

For this type of communication, which I would define as parrhesiastic,1 Pasolini distanced himself somewhat from the figure of the committed, engagé intellectual, for which Jean Paul Sartre had set the example and provided the model. And his distancing was not about a secondary issue, but about something fundamental that touched on the obligation to be truthful, which for Pasolini was something sacred. As is well-known, Sartre chose to suppress some of the truth about the Soviet Union of the time, because denouncing Stalin’s crimes during the Cold War could have risked weakening the communist ‘cause’. When he made this choice, dictated by tactical or prudent reasons, truth clearly became subordinate to political opportunism. Pasolini, on the other hand, always chose truth over opportunism, even when telling the truth could have put his reputation, or even his life, at risk.

An example is his article Il romanzo delle stragi [The story of the massacres], which was published in the Corriere della Sera on 14th November, 1974. Here, Pasolini announced that he knew the names of those responsible for the massacres that had afflicted Italy in those years: the bombs in banks, in stations and on trains, which had killed so many. The first was in the Piazza Fontana in Milan, on 12th December, 1969; the last was at Bologna railway station on 2nd August, 1980 (five years after Pasolini’s death). Each event rocked Italy, as terrorist attacks do now. But in those days, the massacres were not masterminded by international Islamic terrorism, but by powerful groups within the State itself, whose aim was to instil fear and exploit it so that they could hold onto power. It was called the ‘strategy of tension’. The massacres were not attributed to those who were really responsible, obviously, but initially to the communists and later to the fascists. The true instigators, the ‘vertici’ as Pasolini called them (those at the top of the pile), remained hidden.

Here is the beginning of the article, one of the best-known of Pasolini’s ‘corsair’ writings:

Share article