1.

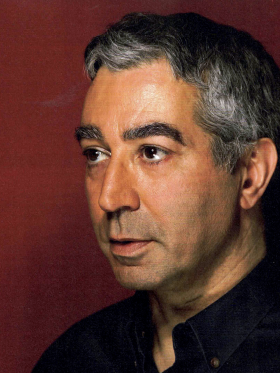

Paul Werner, an artist and cultural critic, has written a book entitled Museum, Inc.: Inside the Global Art World. It is a critical reflection and account of his experience at the Guggenheim in New York. He writes about art institutions at a time of radical change and about art as paradoxical merchandise.

On May 23, 2021, after a year or more in lockdown, Culture went back to normal, as it seemed. Part-time theater workers, street musicians, and other artists suspended their occupation of the Odéon Theater in Paris. Since May 1968, the Odéon has stood for the belief that art can remake life by breaking once and for all with the institutions of art. According to myth, it was from the Odéon that a group of agitators known as the Situationnistes went forth to make art a truly living part of day-to-day existence. As in ’68, so too today there has been an unintentional irony in the spectacle of a group of artists attempting to break with the institutions of art by occupying an institution of art. There has been an additional irony when, in departing, one of the recent batch of rebels read an excerpt from Albert Camus’ Nobel Prize acceptance speech on the responsibilities of the artist, a speech so all-inclusive, so humble in its goals it could have come from any press release from any established art institution:

Each generation doubtless feels called upon to reform the world. Mine knows that it will not reform it. […] Having outlined the nobility of the writer’s craft, I should have put him in his proper place. He has no other claims but those which he shares with his comrades in arms.1

At a time when many in the field of Culture are pondering whether and how the institutions of art (museum practices, systems of social support, economic distribution) might change under the pressure of a catastrophic pandemic year and its uncertain aftermath, these cultural workers seemed relieved to surrender their own responsibility for rethinking the institutional structures of Culture and the personal involvement of artists and professionals. The new radicals were more concerned with preserving the emancipatory promise of Culture, which has formed an integral part of the mission of cultural institutions over the past two hundred and fifty years, than with reinventing the instruments of that emancipation and pursuing whatever this reinvention might entail to the end and making it a reality. At the same time, predictably, the more established participants in the Culture industry seem confident today that the economic effects of the pandemic are passing. As usual, new efficiencies are being called for. Audiences must be developed or re-developed. Otherwise, the expectations are the same, with massive, docile crowds lining up in front of museums. Like their radical friends and rhetorical opponents, but with more consistency, the suits see their mission as merely an adaptation to a shifting economic situation, and do not feel the need to take into consideration the possibility that other aspects of social and cultural life might have suffered a sea change. And while there is no certainty, there is a distinct possibility that the institutions of art might well, in the coming months and years, be forced towards radical changes for which neither the most radical revolutionaries nor the most staid, besuited administrators are prepared. As always with the avant-garde, for everything to change nothing must be changed at all.

"Audiences must be developed or re-developed. Otherwise, the expectations are the same, with massive, docile crowds lining up in front of museums."

Kenneth Noland, Circle, 1958 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Christie’s Images, London

In an influential article, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described ‘The Field of Cultural Production’ as ‘The Economic World Reversed.’2 Here, Bourdieu utilizes a number of concepts all his own, one of which is Field. According to Bourdieu, certain areas of social practice (the art world, for instance) are isolated in part from the outside world in their ways of thinking and conceptualizing, but only in part. They may appear, for instance, to share the same language, but the same words can cover different concepts, to the effect that certain activities, procedures and postures when performed in the context of the art world would have a reverse function from that in the outside world. The French novelist Georges Duhamel records the following dialog between two budding Cubists in the early years of the movement – a dialog based on his own experience:

– Beware! When we’re with the gentlemen, don’t toss around expressions like ‘anarchist’ and ‘individualist.’

– Words are not bombs.

– Of course, but they won’t appreciate the particular meaning we give to such words.3

Among artists, words like ‘Revolution’ or ‘Avant-Garde’ have a meaning radically at odds with what these words, in the mouth of a general or an anarchist, might suggest. The demanding skills required to understand the operating concepts of culture are not merely helpful in distinguishing oneself from outsiders; they’re required of every individual or institution in order to become or remain a fullyfledged participant in the ‘world of art’. The attitudes shared by each and every member of those institutions are also the attitudes enforced by the same institutions, acting as what in legal theory are known as ‘moral agents’: institutions that for all intents and purposes are considered to have the same interests and drives as individuals.

[...]

Share article