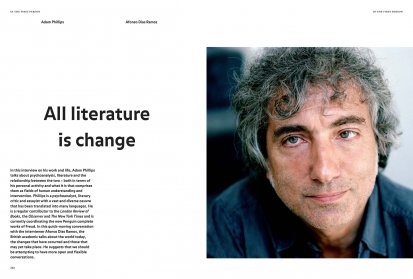

Adam Phillips is one of Britain’s most celebrated psychoanalysts, literary critics and public intellectuals today. He has written twenty-five books about psychoanalysis, literature and culture on subjects ranging from Freud and Winnicott to Sebald and Houdini. He is the General Editor of the Penguin Modern Classic Freud series and a Visiting Professor of English at the University of York. His new book, On Wanting to Change, is about how and why we change, and the urgency of having conversations rather than conversions.

Adam Phillips, formerly Principal Child Psychotherapist at Charing Cross Hospital, London, is a practicing psychoanalyst and visiting professor at the Department of English at the University of York. Widely considered to be one of the leading psychoanalysts and literary critics in Britain, Phillips has authored twenty-five books, which include Attention Seeking (2019), In Writing (2017), Unforbidden Pleasures (2015), Becoming Freud (2014), Missing Out (2012), Intimacies (with Leo Bersani) (2010), Darwin’s Worms (2000), On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored (1993), and Winnicott (1988). A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, Phillips is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books, The Observer, The Raritan, and The New York Times, and has edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Lamb, Walter Pater, John Clare and Richard Howard. Among his notable admirers are writers such as Will Self, Zadie Smith, and Jonathan Safran Foer. As one of the most prominent experts on Freud and the history of psychoanalysis, Adam Phillips was also invited by Penguin Press to serve as General Editor of the new English edition of the complete works of Freud in seventeen volumes, reintroducing him to the public, less as the author of scientific texts than as a major literary figure in his own right.

Adam Phillips has been called by John Banville ‘one of the finest prose stylists in the language, an Emerson of our time’, and was praised by Judith Butler as one of the few authors today to have ‘thought and rethought psychoanalysis in powerful terms for contemporary culture.’ More than any other critic, his essays theorise the relationship between psychoanalysis and writing, therapy and reading, recasting it as a closer cousin of literature than science. The catchy but deceptively simple-sounding book titles include perceptive and erudite essays that cover a broad range of topics, from Nietzsche to Pessoa, Shakespeare to Lacan, Karl Kraus to Marianne Moore, Jean-Bertrand Pontalis to Frederick Seidel. They encompass everything from theories of couture and clutter to histories of hinting and first impressions. The signature epigrammatic style informs the provocative urge to turn modern clichés on their heads, whether arguing against the idea of self-criticism, self-knowledge and diagnosis, or championing solitude, boredom and attention-seeking behaviour.

This interview for Electra was conducted over the phone only days after the release of Adam Phillips’ new book, On Wanting to Change (2021), in which the foremost literary psychoanalyst picks apart the constant contemporary injunction to change our lives as part of a liberal myth of progress that condemns the idea of conversion harking back to Saint Paul and Saint Augustine. In this conversation, Phillips talks about some of his work as a literary essayist, and the future of psychoanalysis.

Share article