But what did it mean (if it is true, as poets say, that a dress means something?1 Stéphane Mallarmé, La Dernière mode

Goddess of goddesses, sphinx of sphinxes, mystery of mysteries, Madame Grès shone brightly in the exclusive world of Parisian haute couture. Her legacy was her ceaseless quest for absolute beauty in her designs. Her long, draped dresses crafted with obsession and technical mastery are a profound reflection on fashion, time and memory. Anabela Becho, a fashion curator and researcher, describes the life and work of this great couturière.

But what did it mean (if it is true, as poets say, that a dress means something?1 Stéphane Mallarmé, La Dernière mode

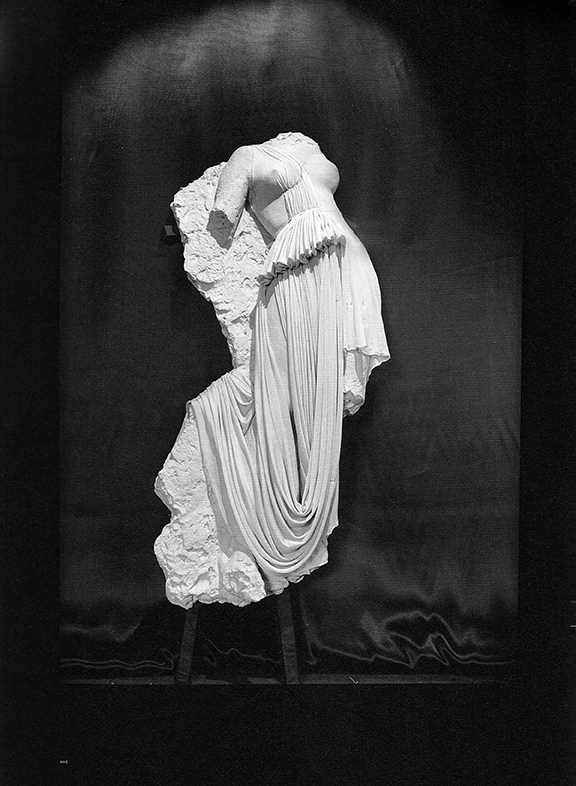

Photograph by George Platt Lynes, 1940

Silence. It all began and ended in silence. Her long life was threaded throughout with silence. Everything revolved around silence. Except her work, which was born in and of silence but was anything but silent. It has always spoken out loudly, assertively and eloquently, but never harshly. In its undying association with sculpture, it encloses an inherent affirmative, a solid, timeless perpetuity. Respect for the principles of design is seen throughout Grès’ discourse with textiles. This is a discourse, a thought transformed into matter, that grows in an incremental game of pleated light and shade enclosing successive pain and mystery, melancholy and persistence, obsession and conviction. The folds enclose pain and mystery, melancholy and persistence, obsession and conviction. There can be no doubt that Grès’ gowns were designed for the female form, in the cutting and manipulation of the fabric, in a prodigious, precise technique in which nothing could be left to chance. This is why they are perfect examples of the highest calling of design. Nonetheless, it is precisely in the relationship between body and gown, the harmony and tension between the organic and inorganic,2 that Grès’ work goes beyond mere design. It moves naturally into the real world of creation, as the couturière’s gowns do not just dress the body – they become the body itself, in which fabric and flesh turn into a single, indivisible, absolute entity.

Grès’ work was unmistakably modern, though it did not seem to belong to any particular age. It is timeless and remits the past while also looking to the future. The evocative power of her gowns is breathtaking. It is ingrained in their materiality, the details of their construction, the quest for perfection and for beauty. Although she was a woman of her time, associated with a certain artistic, cultural, social and political milieu, we can see at the heart of Grès’ work a deliberate search for timelessness and an undeniable creative momentum. Grès was strong-minded and created her own fashion with no regard for fashion trends.

When we look back at Grès’ life, we inevitably come across the aura of mystery she cultivated. She hardly ever gave interviews. Information about her life is often contradictory, and there is very little biographical material. Grès regularly reinvented herself and took on different personae throughout her life. Meticulous, obsessive, austere and monastic, she lived a private life, far from the spotlights of the world of fashion under which her creations shone brightly.

"Grès' work was unmistakably modern, though it did not seem to belong to any particular age. It is timeless and remits the past while also looking to the future."

She was born into a petit bourgeois family in Paris on 30 November 1903. She was baptised Germaine Emilie Krebs, a name she claimed to have hated, perhaps because she felt it was not distinguished or special enough. Little is known about her childhood, except that she had an innately artistic view of the world, with a particular affinity for sculpture and dance. It may be fair to say that the body was her main frame of reference: the perfect, sculptured marble body, and the body in the modern dance moves of Isadora Duncan, who came to fame when Germaine was young.

She worked for sixty years. Initially going by the name of Alix, she created and recreated gowns as if they were living sculptures, meta-gowns, the dress of dresses, designs that she invented, crafted, perfected and purified. Her creations were three-dimensional, in an affinity with classical sculpture:

I never create a dress from a sketch. I drape the material on a mannequin, then I study its nature, and only then do I take up my scissors. The cut is the most critical and most important phase of the creation of a dress. For each collection I make, I completely wear out three pairs of scissors. (Grès quoted by Hata, 1980: 254)

Half-toile of a dress presented in a bas-relief at the New York World Fair in 1939

The half-toile presented in New York in 1939 is photographed again in 1954 by Willy Maywald

While coherence is a characteristic feature of Grès’ work, there are still some contradictions although they do not compromise its integrity. In spite of the fact that she said that she never created a piece from a drawing, there are numerous quick sketches in the collection at Palais Galliera Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris. She drew them herself to explore the potential of draping, and they clearly show that pencil and paper were useful for inspiration and experimentation. Another discrepancy is the classical inspiration always attributed to her work, which Grès both embraced and denied:

You have to want to do something with something. They say that these draped gowns are inspired by Antiquity. But I’ve never been inspired by it. Before this fabric existed (a delicate silk jersey), I hadn’t even thought about draping. But as soon as I got the fabric, it fell into place on its own. Greek sculptors made their sculptures from the materials that were best suited to them. (Alix Grès L’Enigme d’un style, 1992: 16)

"Grès regularly reinvented herself and took on different personae throughout her life. Meticulous, obsessive, austere and monastic, she lived a private life, far from the spotlights of the world of fashion under which her creations shone brightly."

In the early 20th century, Paris was a hothouse for the most avant-garde artistic movements such as cubism and surrealism. It was a place of freedom and creativity where a thirst for classicism began to emerge, similar to the neoclassical movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In fashion, Paul Poiret (with Directoire or Empire style high-waisted, neoclassical-inspired dresses) and Mariano Fortuny (with his Delphos and two-piece Peplos gowns in pleated silk) sowed the seeds for classically inspired clothes. Also in the 1910s, Madeleine Vionnet liberated the female body by enveloping it naturally and harmoniously capturing the most beautiful essence of classical aesthetics – the relationship between the body and movement.

Always with her eye on the future, Alix began her career in 1933, and based her aesthetic identity on classically inspired methods using the latest textiles. In a tiger’s leap3 into Antiquity, she reinvented an ancient Greek style — chiton, peplos and himation – for modern times. She used modern, malleable, delicate fabrics, especially silk jersey, many of which were made exclusively for her by renowned textile companies such as Rodier.

In 1935, Alix created Greek-inspired costumes for Jean Giraudoux’s play La Guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu, directed by Louis Jouvet. Classical antiquity stood for a utopian vision of purity, stability and unity at a time of political and social instability – the period between the two world wars.

(...)

Guy Bourdin, Vogue Paris, March 1976

© Photo: courtesy Louise Alexander Gallery / The Guy Bourdin Estate 2021

Share article