A.

Laurent de Sutter is professor of legal theory at Vrije Universiteit Brussel and managing editor of the series Perspectives Critiques (PUF – Presses universitaires de France). Here he develops a hypothesis that, under certain conditions, accepts accelerationism – i.e. the perspective that advocates reformulating and not sabotaging or damping down the means and the infrastructure that we have inherited from modernity.

Since its publication in May 2013, the ‘Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics’ has been read as a hidden apologetic defence of our surrender to the technological fate that humanity has pursued since the birth of modernity – and then to the destruction of our lives, our democracies and even our planet. This accusation, however, is as absurd as it is deliberately contrary to the very letter of the ‘Manifesto’, which states that what we need at the present time is, precisely, a redesign of what we have inherited from modernity in general, and the Industrial Revolution in particular. The true goal of Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, the two authors of the ‘Manifesto’, was not to dig deeper into the fatal hole that we have been drilling for centuries, but on the contrary to reinvest in the means that we have used in order to drill this hole with the purpose of undoing it. If ‘neoliberalism’ is the name of the vision defending the acceleration of the present situation, then ‘accelerationism’ is the name of the vision fighting that acceleration and trying to defend another one – intense enough to attract us outside of the sphere of influence of the former. In order to do so, wrote the authors, there is at least one condition to be fulfilled: the acknowledgement of the fact that, as a political, economic, ecological and technological enterprise, this new form of acceleration cannot be based on the fantasy of a tabula rasa. Instead, we have to take into account the state of the present – and, with it, the type of world that has been built and equipped by the tenants of capitalism: a world whose main feature is not so much its ideological superstructure as its material infrastructure. The history of modernity, in particular since the Industrial Revolution, has mainly consisted in the endless building up of a gigantic infrastructural network not only determining what is possible and impossible in the world, but also reshaping this world itself. The world we have inherited from modernity is the world of infrastructure – be it roads, bridges, tunnels, rail tracks, delivery systems, internet cables, warehouses, water ducts, oil and gas pipelines, high-tension electric cables, data centres, or whatever. Every single aspect of our lives, from the cradle to the grave, has become integrated into an endless series of infrastructural devices and processes, without which there would not be a world at all – or, at least, a world that supports the contemporary conditions for life to simply exist.

B.

It is all too easy to see logistics and infrastructure as a curse. It even has become a common trope of critical thinking to denounce the way capitalism has transformed itself into some sort of logistical nightmare, whose main example is the super container ship, loaded to the rim with containers full of goods illustrating the globalization of exploitation. Indeed, it is true that the development of infrastructure in the 20th century has accompanied both the liberalisation of work at the level of the planet and the degradation of its ecological condition – which it has undoubtedly helped to worsen. Yet, at the same time, the development of infrastructure is what has allowed dozens of millions to enter a new phase in their existence and, for better as much as for worse, become part of a world from which they were simply excluded before. Since infrastructure is what makes the world, it is impossible not to see how the very existence of a world was, until very recently, something reserved for a tiny majority of the Earth’s population – whereas, now, a larger share has gained access to it. Of course, to become part of the world implies becoming part of the problem into which the world itself has metamorphosed, since infrastructure has a cost – and this cost is what has been overlooked for too long by those who have profited the most from it: the very proponents of infrastructure. As such, then, there is no doubt that infrastructure is a curse: as every curse, it is at the same time something that renders almost everything impossible – and something without which absolutely everything would be impossible, because there would not be a world allowing for any possibility to start with. This implies that there are only two choices left to us, as far as infrastructure is concerned: to start all over again from scratch, which would imply a cost way beyond any capacity to bear it; or to deal with what we have and try to build something else out of it. If we are to put this alternative in the terms of the ‘Manifesto’, the choice is between ‘folk politics of localism, direct action, and relentless horizontalism’ and ‘[preserving] the gains of late capitalism while going further than its value system, governance structures, and mass pathologies will allow’. But it is not really a choice. The first option of the alternative is only but a daydream cherished by those who already have everything and are ready to leave behind all those who do not share their luck – which precisely relies upon the existence of neoliberal infrastructures.

C.

Despite both its lack of realism and its somewhat disgusting contempt for others, this daydream is gaining greater and greater traction in the Western world – not only from collapsologists and environmental survivalists, but also from their very nemeses. As a matter of fact, those who are the most actively preparing for a radical transformation of our ways of life outside the realm of neoliberal infrastructure are the architects of neoliberal infrastructure themselves. Be they Silicon Valley tycoons or public works entrepreneurs, the new masters of the networks that have made the world that we are inhabiting are the ones who are taking the most urgent steps in order to leave it and develop some sort of new self-sufficient paradise.

"The new masters of the networks that have made the world that we are inhabiting are the ones who are taking the most urgent steps in order to leave it and develop some sort of self-sufficient paradise."

Buying land in New Zealand, and building self-sustainable farms and equipping them with all the technology needed to produce energy, heat and clean water (without forgetting sewers in order to get rid of residues), they are using their immense financial resources to create a new form of primitive Arcadia where they can become the sole rulers. The irony is that this form of neoliberal survivalism is precisely what the tenants of folk horizontalism, de-growth and voluntary simplicity are advocating, without taking into account that such a simplicity has now become the supreme form of luxury. The example of the Silicon Valley tycoons illustrates it well: rebuilding a world outside the world, for the sole enjoyment of its owners, is the logical conclusion to the history of liberalism as anchored in the fantasy of autonomy and ownership. Such a miniature world, however, if it is to be self-sufficient, needs the most precious products of contemporary technology, such as solar panels, heat extractors, etc., in order to be even conceivable; it needs to reinvent its own infrastructure. This means that, whatever the project, one cannot get rid of infrastructure because one simply cannot get rid of the necessity of a world – as there is no such thing as a natural world where human beings could spontaneously live. As the long history of the development of the human races has shown, the environment is a hostile milieu, hostile to the form of life that we are until the moment when we transform some of the factors sustaining this hostility into adjuvants for our own safety. From the very first trails spontaneously trodden by hominidae to the fiberglass cables transmitting digital data, there is nothing but continuity.

"This form of neoliberal survivalism is precisely what the tenants of folk horizontalism, de-growth and voluntary simplicity are advocating, without taking into account that such a simplicity has now become the supreme form of luxury."

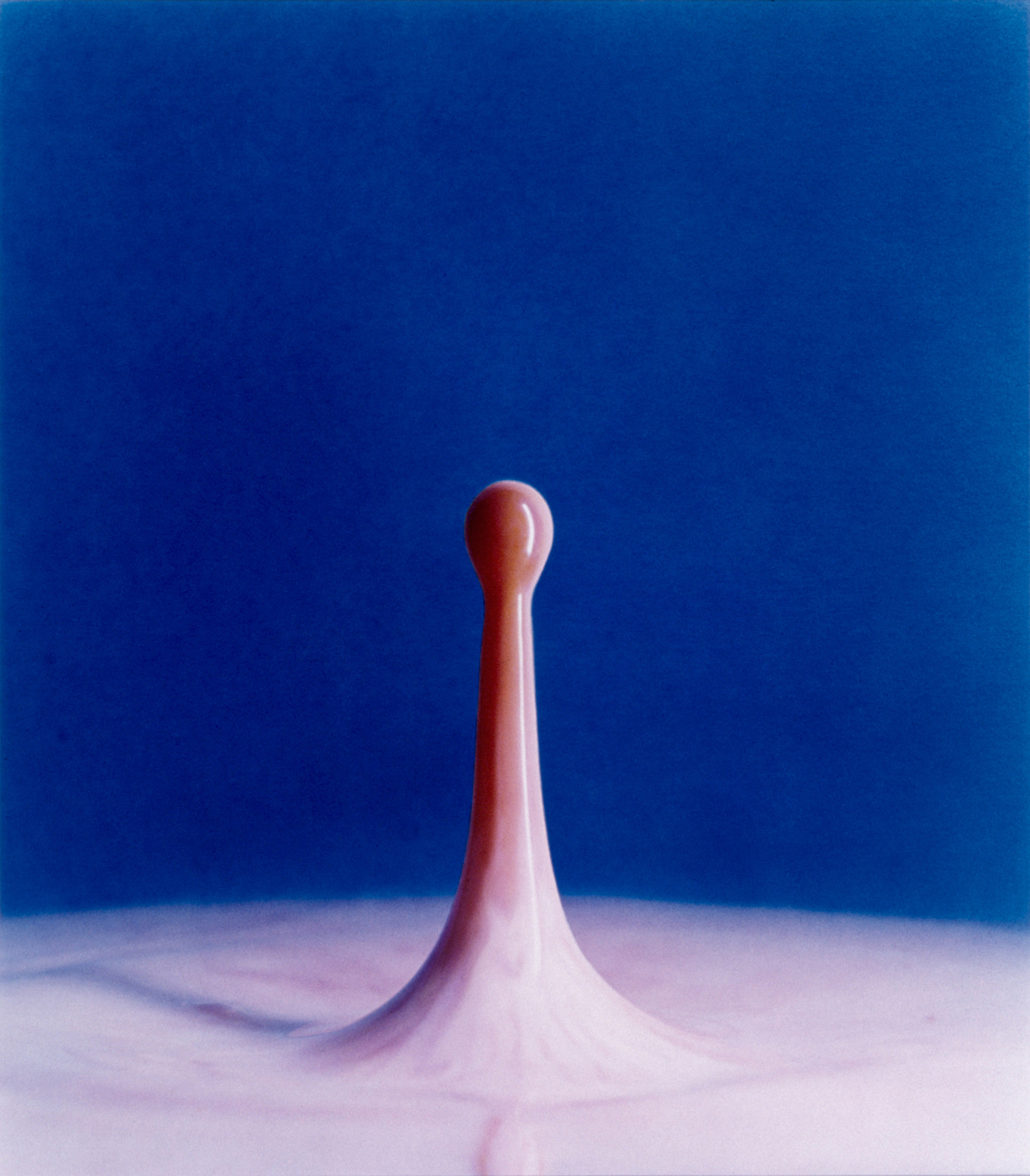

Harold Edgerton, Cranberry Juice Dropping into Milk, 1969

© Photo: MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology / Courtesy MIT Museum

D.

Before anything else, accelerationism is the acceptance of this reality. Such an acceptance, however, is not some sort of fatalism – a way of claiming that there is no way out of our current predicament, or even out of the human condition as it is framed by infrastructure and logistics. It is rather the opposite: it amounts to claiming that the only way out of our current predicament and its dramatic consequence for the Earth’s ecosystem at large (including our own) must put the actual state of infrastructure and logistics at its starting point. In the ‘Manifesto’, however, what is meant by ‘infrastructure’ or ‘logistics’ is not particularly expanded upon; the examples provided by the authors could even lead us to think that ‘infrastructure’ and ‘logistics’ only concern what they call ‘platforms’, as in Facebook or Google. Among the three important tasks facing accelerationism according to them, they go even as far as to state that we need to rebuild what they call a new ‘intellectual infrastructure’ able to compete with the one that has been successfully elaborated by neoliberals since the advent of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947. This could imply that the accelerationists are only interested in media, understood in the strict sense, that is, as the dispositive of the transmission of information that was born of the invention of the telegraph and allowed the creation of the modern press, radio, television and the Internet.

"The only way out of our current predicament and its dramatic consequence for the Earth’s ecosystem at large (including our own) must put the actual state of infrastructure and logistics at its starting point."

It would be a mistake to draw such a conclusion, however, as what is emphasized in the examples given in the ‘Manifesto’ is not so much these media themselves, but rather the type of materiality that gives them their reality. When they speak about the press or the Internet, Srnicek and Williams do not speak about the press and the Internet – they really speak about the infrastructure of steel, concrete, microchips, etc., upon which they rely for the transmission and processing of information that would otherwise remain insignificant. In that, they remain true to a very important Marxist article of faith: the one stating that the means of production always plays the primary role in the process of production itself – and that the rest is basically only ideology. When they mention infrastructure, the authors of the ‘Manifesto’ do not so much try to raise awareness about the role played by media platforms such as Facebook or Google in the consolidation of the neoliberal agenda, but rather of the fact that they are platforms before being words, discourses or images in our lives.

E.

Speaking of platforms, Srnicek and Williams urge us to start thinking about a way to redistribute the cards giving primacy to a couple of media types over all the others. Their first call for action concerns the need to build as soon as possible new platforms, based on the model tried by neoliberal businessmen, in order to provide an alternative to their profit-driven ventures. Such a platform could then contribute to the third goal set forth for accelerationism, namely the need to recreate a strong, grassroots, connection between what they call ‘a disparate array of partial proletarian identities’ – in short, the losers of neoliberalism. If such a belief in the efficacy of social networks and the Internet is to be saluted, we cannot help but wonder if this is all that the very idea of accelerating infrastructure could entail – or if, on the contrary, it is necessary to move way beyond. Among the few thinkers of the Left who have dared to address the question of infrastructure in recent times, the Invisible Committee collective has, at least, suggested that going for it is also going for a simple truth: the world, as based upon infrastructure, is weak. If people want to stop the functioning of this world, they just have to cut a few cables, block some pipes, pollute a couple of reservoirs or disrupt the delivery of goods for a few days – and everything would crumble. Taking into account the centrality of logistics and infrastructure cannot be limited to the designing of some Leftist Facebook, but has to acknowledge the fact that they are what make things possible – and then also impossible. Deciding on the possible and the impossible is a power that no longer lies in the hands of human beings, but in those of concrete, tarmac, steel, oil, etc. This is something that the Yellow Jackets, in France, have perfectly understood. When they decided that it was time for them to express their anger and sense of being left out, they did not go for demonstrations on the customary trails of Paris, but occupied roundabouts and crossroads – and then started their demonstrations, but in other quarters of the city. If the French authorities were so scared of them, it is not because they were more numerous or aggressive than others (they were not), but because they chose places of action that were more crucial in the process of deciding what is possible and what is not. They made them visible to all – and showed the world how fragile they really are.

F.

This negative, revolutionary, take on what to do with infrastructure is absent from the ‘Manifesto’. For Srnicek and Williams, it was more important to insist on the dimension of progress implied by the very existence of such infrastructure – as the price to pay if one was to destroy the existing one in order to build a new one is too high. Since the current state of infrastructure is the result of more than a century and a half of exceptional growth, fuelled by the discovery of new (but soon to be exhausted) energy resources, it constitutes a miracle that no one will ever have the chance to replicate. The authors are very pragmatic: what matters, rather than disrupting actual infrastructure, they say, is to hack it – as hacking is way less costly and way easier than building. But even in the case of hacking, the coming accelerationist Left would have to ask itself the question of the resources needed in order to do so – resources both at the purely material and at the financial levels. The problem is that they do not precisely define how such funding will be made available, except for stating that resources should be asked from ‘governments, institutions, think tanks, unions, or individual benefactors’, which presupposes that they will be willing to give. Another possibility, also set forth by the Invisible Committee, is slightly more brutal: it consists of stealing whatever can be stolen from places where money is easily available. Sixty years ago, Belgian Surrealist artist, poet and thinker Marcel Mariën, already calling for some kind of logistical revolution based on taking over the media, went even further, suggesting that a systematic criminal network should be set up in order to rob capitalists.

As unrealistic as these proposals may be, they put a finger on a very concrete issue that has only been tackled recently with the advent of crypto-currencies, capable of creating wealth outside the scope of the state or corporate capital. Some thinkers have gone as far as to state that this advent would mark the possible date of birth of a new form of communism, called ‘cryptocommunism’, as, for the first time in history, value would become a problem of creation rather than extortion. Whatever one thinks about such ideas, there is indeed an important accelerationist lesson to be drawn from them: if one is to take the infrastructure of money seriously, one also has to think about the way such infrastructure may be taken over, and then reoriented in another, progressive, direction.

Marcel Duchamp, Rotoreliefs [Optical Disks], 1935

© Photo: Scala, Florence / The Museum of Modern Art, New York

G.

Despite these three limitations (the concentration upon media platforms, the lack of a revolutionary stance and the vagueness of its proposals à propos funding), the gesture of the ‘Manifesto’ is radical – at least in the recent history of the Left. Taking infrastructure into account as the most crucial area of political constraint in the contemporary scene can even be considered as a paradigm shift from the point of view of Leftist theory, as it breaks firmly with what remains its everyday doxa. By focusing on concepts such as ‘emancipation’, ‘equality’, ‘democracy’ or ‘labour’, Leftist theory had for a long time deserted the field of the conditionality of all those concepts – of the fact that the reality that they entailed was not a natural reality. If one is to fight for emancipation, equality, democracy, or liberation from the tyranny of labour, then one has first to measure the depth and importance of the conditions laid upon this task for it to be fulfilled.

"Taking infrastructure into account as the most crucial area of political constraint in the contemporary scene can even be considered as a paradigm shift from the point of view of Leftist theory."

To put it in lay words: Srnick and Williams are the first to have insisted upon the price that there is to pay for a change in the world – as conditions always mount up for an augmentation of the difficulties that a given task has to overcome in order not to fail. This means that, contrarily to the majority of Leftist thinkers, they have made the horizon of emancipation, equality, democracy and so on, more difficult to reach, rather than less – even though, by raising the bar, they have also made it more realistic. Alain Badiou is one of those who have relentlessly insisted upon the fact that politics is always rare and always conditional; to some extent, we can consider that the authors of the ‘Manifesto’ have meditated well on this lesson. It is not enough to have ideas and to be ready to go onto the streets to demonstrate (without even speaking of voting); one also has to develop a strategy that goes way beyond obedience to the rules of the game – and attempts to change these rules. If they are the ones stating that politics, whether progressive or conservative, is precisely all about rules, then those who see past these rules, and observe how neoliberals have achieved their success by not playing by them, will have better chances. This is why the ‘Manifesto’ should be read as it is: not as a manual for the aspiring revolutionary, nor as a programme for flawless success, but as a strategic proposal that will only have the meaning that those who use it give it by using it.

H.

Perhaps the best example of this pragmatic dimension of the ‘Manifesto’ is its first offspring, beyond Srnicek and Williams’ later work on post-work, namely xenofeminism. It has not been stressed enough how the ‘Xenofeminist Manifesto’ was linked with the proposals of the ‘Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics’, that is, how xenofeminism should be considered as a form of accelerationist feminism. By arguing that the female body, contrarily to what some essentialist feminists are defending, is not some sort of sacred ground that should be protected from the outside at all costs, the xenofeminists argue that it has not been alienated enough – and that should be the task facing contemporary feminism. With ‘alienating’, what Labora Cubinks, the collective authoring the ‘Xenofeminist Manifesto’, meant was very clear: it was about outlining how the body had always depended upon external forces for it to construct its own power, its own capabilities. These external forces, however, are not mainly ideological (the ‘discourse’ on the female body, etc.), but physical and material: food, sleep, exercise, medication, and so on. What has been alienating women from their bodies for so long is the technical-chemical infrastructure defining the limits assigned to the capabilities and aesthetics of the body. This is why the xenofeminists argue that it is high time for women to reclaim the power over this infrastructure, and appropriate it in a way that can allow them to construct their own alienation of ‘themselves’ – their own way out of the sacred vessel of the body. Such a claim, they say, can imply, for instance, investigating the realm of DIY hormones, as hormonal control, mainly through the contraceptive pill, has been one of the central concerns of the police infrastructure surrounding female bodies since the discovery of the functioning of the endocrinal system. It is exactly the same with accelerationism: what Srnicek and Williams have wanted us to be aware of is the deepness and intimacy of the role played by infrastructure in our lives, and how it structures the possibilities for action, and even simply thought, left to us. A brighter future will never appear as a mere exercise of the will, or as the result of a struggle between opposing forces – since every force, in the contemporary world, is never itself, but the result of the infrastructure that it can convene. A brighter future can only be the future of a brighter infrastructure.

Share article