Irrespective of his methodological daring, we owe to Virilio a systematic reflection on speed and technological acceleration, at the dawn of the new regime of electronic speed, from which he drew conclusions regarding its ecological consequences long before they became evident: not pollution through the dissemination of toxic products, but the pollution of extension and duration, i.e. the elimination of space and the abolition of time.

The identification of Paul Virilio’s name with the question of speed became immediate and almost automatic for very good reasons. But, before him, we find important reflections and insights in the 19th-century explorers of the philosophy of technology, particularly in a sociologist who knew how to analyse and interpret, in depth, what he called ‘surface phenomena’: Georg Simmel. And some of the surface phenomena that he detected in large cities, for instance, as the quintessential spaces of modern life, led him to define the ‘pace of life’ as the product of the representations of consciousness per unit of time. Simmel had realised that everything in modern society had begun to accelerate and that the time of the formation of cultural phenomena and social life was increasingly shorter.

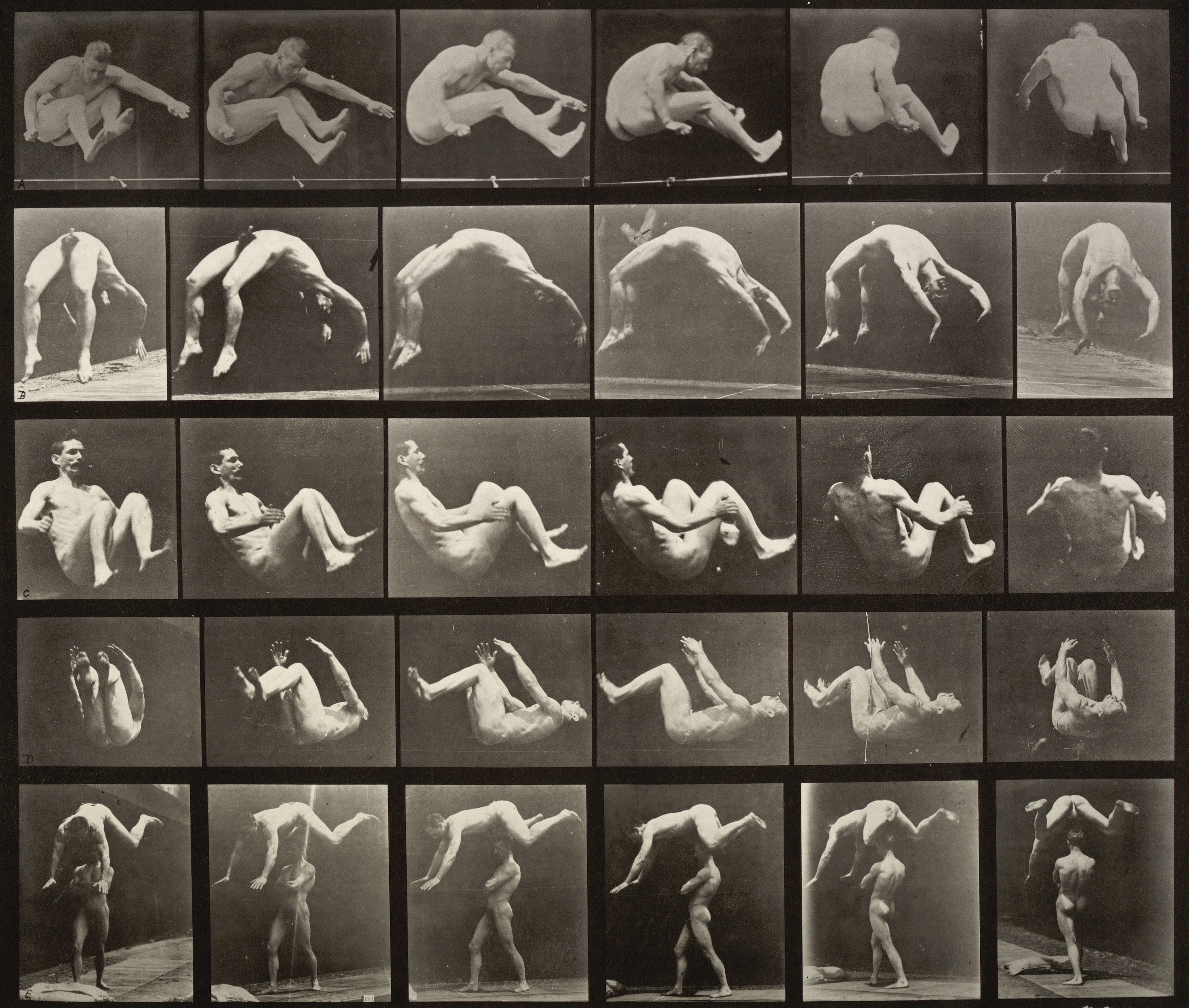

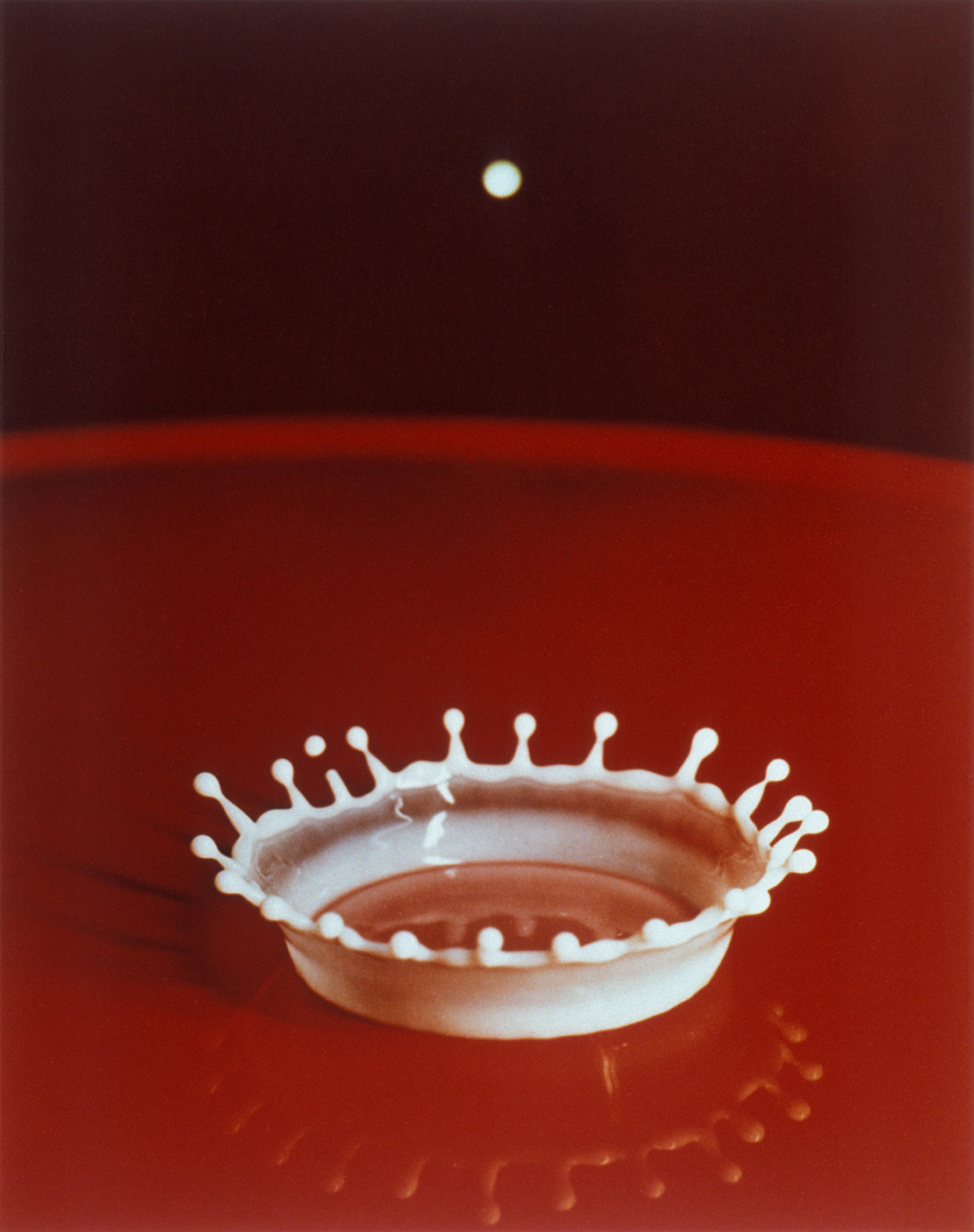

In his theoretical work, Paul Virilio presents a coherent narrative, which draws on a wealth of information and a rigorous power of synthesis to enumerate a series of revolutions: after metabolic speed (of horses, for example) comes the dromological revolution of the industrial age (the technological speed of trains, cars, aeroplanes, etc.), followed by electronic speed, i.e. the speed of light, which is the very limit of speed. At the end of this analytical path Virilio reaches the paradoxical thesis that we are tending towards absolute inertia, evolving from greater and greater mobility to a condition of confinement, a ‘rushing standstill’, to borrow an eloquent metaphor from the author of L’inertie polaire (2002). Thanks to speed-of-light technologies everything comes to us without our having to move. Therefore, says Virilio, we are witnessing the emergence of a new era, which he calls ‘the era of generalised arrival’, replacing the era ‘of limited arrival’, when movement had a particular duration.

The situation that we are experiencing today after a sudden and unexpected halt on a global scale, where the only thing that became faster was internet traffic (since the mandate to ‘social distance’ resulted in a greater reliance on virtual activities), clearly illustrates Virilio’s thesis of a ‘polar inertia’, where the immobility of the physical world becomes stronger as our lives accelerate in the digital world.

Paul Virilio analysed the speed phenomenon in its relationship with disaster and catastrophe. There is no optimism in his view, no matter how exciting his descriptions of our current and future world, dominated by the speed imperative, may sound – we could even say there is a degree of fictional euphoria to them. War machines, vision machines, acceleration machines: the world that he describes seems to transport us at times to a futuristic universe, but without the euphoria of futurism. He would never subscribe to Marinetti’s statement: ‘The splendour of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.’ In the end, even if not always explicitly, a criticism of technology is implied in all of his work, which can thus be placed among the great critiques of technological modernity, whose epitome is found in Heidegger. According to him, the frenetic quest for total acceleration corresponds to a global history of decadence, a continuous experience of destruction. When he organised an exhibition at the Cartier Foundation, entitled precisely La Vitesse, his aim was not only to show the beautiful and useful results of the technologies of speed, but also to highlight the violence, the war paraphernalia and the post-human dimension (even though, at the time, this concept was still far from gaining the theoretical popularity that it has achieved) inherent in the anonymous and coercive logic of increasing speed. We can say that Virilio was the first to shape the imagery of endings and catastrophes as it has been cultivated since the beginning of the 21st century. The main reason for his pessimism is also political and might be explained in the following way: there is an effect of irreversibility in speed (no regression is possible; at every maximum level that we reach, we never go back to an earlier stage where everything was slower), to the point where speed arises as a ‘natural’, apolitical force, over which there can be no control. With dromology, Virilio asks the following question: can we still use the political mechanisms of control, if we do not control speed and we allow techno-science to continue down its irreversible path (despite knowing that we are headed towards disaster)? Hence his provocative proposal: in the same way that there is a political economy of wealth, we need to create a political economy of speed.

In the following dossier, on speed and acceleration, which comprises the ‘Subject’ section of this issue of Electra, we have tried to trace a route through the current state of the speed question, as it arises in many disciplines. Among the obligatory stops is the problem of the acceleration of history, central to the theoretical work of the French historian François Hartog. The article that he wrote for this dossier is an excellent overview of the issue of acceleration and its relationship with ‘presentism’, i.e. a historical temporality that completely erases the future from our horizon. Hartog is the contemporary historian who brought the concept of acceleration into the theory of history, and into the definition and analysis of historical temporality, which he has developed with great conceptual sharpness, in particular in a book entitled Régimes d’historicité. Présentisme et expériences du temps (2012).

In another disciplinary field – sociology – we find the most important contemporary work on acceleration and speed: that of the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa, a professor at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena. In 2005 he penned a fundamental book, entitled precisely Beschleunigung, i.e. ‘Acceleration’ (but we should also mention Beschleunigung und Entfremdung [Acceleration and Alienation], 2013). His project, a wide-reaching enterprise, consists of a ‘social critique of time’. With relative ease, we may identify the lineage to which Hartmut Rosa belongs, or, at least, the sociological constellation that preceded him: the critical theory of the Frankfurt School. In that monumental work from 2005, Hartmut Rosa, who has reached the status of an academic star, develops a theory of modernity as a culture determined by generalised acceleration – and the shift to ‘late modernity’ in the 1990s is a crucial stage in this acceleration, as analysed and described by him. The acceleration takes place on three planes – three dimensions of social acceleration – which can only be separated in theoretical terms: technical acceleration, acceleration of social change, and acceleration of the pace of life. Hartmut Rosa devotes a chapter to each of these planes. Technical acceleration implies the use of machines and processes towards a particular goal. As for the acceleration of social changes, it pertains to the rhythms of social transformation, e.g. changes in work, political parties, or in family and professional structures, artistic styles, etc. Finally, the acceleration of the pace of life is defined by an increase in the number of episodes of action or experience per unit of time (we are very close here to Walter Benjamin’s thesis on the poverty of experience in modern times, when personal experiences no longer correspond to an established, collective time and thus do not become transmissible experience).

With technical acceleration, visible in all domains of social life, particularly in transportation, communication and consumption, the planet has become much smaller. Hartmut Rosa mentions studies that indicate that the Earth seems sixty times smaller than it did before the revolution in transportation. Acceleration encompasses every aspect of existence. The world described by Hartmut Rosa (that we know very well) is the one that imposes an increasingly faster pace, to the point that we need to make an effort to remain in the same place (like the hamster that runs at full speed to keep up with the wheel that it spins). In the portrait of modernity drawn by this sociologist, time accelerates and devours us, as Chronos did with his children: professions change every few years, technologies become obsolete even faster, no job is safe, traditions and trades disappear, couples do not last, families are constantly being remade, and the short term reigns in every domain, including political management. And the fundamental law of economics, now invested with an overwhelming force that no one can contain, translated into this formula with an absolute value: time is money. All of this is carried into the subjective sphere, where the feelings of urgency, guilt and stress, the anguishing schedules, and the need to constantly accelerate are amplified. Therefore, it is no surprise that the great illness of our time, created by social acceleration, is burnout, i.e. the state of exhaustion caused by excessive work and the demand that we perform several activities simultaneously (multitasking). We should also note, given its important implications, that this acceleration has its opposite pole in unemployment, i.e. the exclusion from the system ruled by generalised acceleration.

Moreover, Hartmut Rosa shows how acceleration determined generation gaps that stem from the shortening of time: in the first half of the 20th century, i.e. high modernity, the gap was between grandparents and grandchildren. The first knew that their grandchildren’s present was different from their own and that they did not have much to teach them. The latter would become the vectors of innovation, of a new world. What we are seeing in our time, i.e. late modernity, is that the world changes more than once in each generation. Now, it is the parents who have nothing to teach their children – it is even possible to hear an eighteen-year-old youngster say that his ten-year-old sibling is from another generation, or belongs to another time.

At a certain point in the book Hartmut Rosa asks: ‘Why does everything in modern society seem to get faster and faster?’ His explanation for this dynamic consists in the principle of the ‘spiral of acceleration’, in the fact that modernity’s social acceleration is a self-reinforcing process. That is, acceleration constantly engenders more acceleration and reinforces itself in a circular process. Hence his thesis about acceleration as a totalitarian process (we could probably say, borrowing a famous formula by Marcel Mauss, a total social fact) that creates alienation, curbs autonomy and becomes highly oppressive.

Another word (almost a concept, in fact) should be apprehended from Hartmut Rosa’s social critique of time: ‘desynchronisation’. The serious ecological crisis that we are now facing can be understood as a problem of desynchronisation: natural resources are exhausted at a much faster pace than the ecosystems can reproduce them, and the divide between the tempo of ecosystems and that of human activities is accentuated. The desynchronisation between the political sphere and the economic and financial sphere is the chief political problem of our time. This has led some authors to predict the end of politics, since the latter has been condemned to an inevitable desynchronisation between, on the one hand, its particular tempos and modes of deliberation and, on the other, social changes and economic and financial fluctuations.

Hartmut Rosa is the great contemporary theorist of the acceleration of technology, society and the pace of life. His theories and representations about late modernity have gained great traction, but have not exhausted the field. As a counterpoint to his project of sociological analysis, a controversial and untimely text entitled #Accelerate. Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics appeared in the U.K. in 2013. Authors: two English university professors, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams. This manifesto constitutes another central moment (treated in the Laurent de Sutter text included in this dossier of Electra) in the theories of acceleration and speed that have emerged in our time. Going against the grain, the #Accelerate Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics proposed that acceleration should be exacerbated, that the logic of capitalism should be carried to the limit of exasperation – unlike a certain Left obsessed with the many forms of resistance to capitalism. In other words, instead of fighting it, we should overcome it through the appropriation of its logic. Overcoming neoliberal capitalism and reviving, for the Left, an idea of future that has been lost: this is what the authors of the #Accelerate Manifesto suggest. Therefore, to accelerate means to dominate what has dominated us, using its own logic, i.e. seizing the achievements and infrastructure of capitalism, from logistics to finance, and transforming its material structures from within. Instead of the negativity and self-indulgent resistance in which

the Left has delighted since it has become bereft of a positive outlook and ceased claiming the future, the #Accelerate Manifesto offers it the chance of being affirmative. Evidently, there is a scientific and technological optimism here that seems to want to restore an old ideology of progress and risks falling into a ‘demented Prometheanism’, as the philosopher Yves Citton observed (he translated the manifesto into French for the Multitudes magazine, of which he is the subdirector; we include a text by him in this dossier). One of the most controversial points of the #Accelerate Manifesto might be the one where the authors write:

Share article