The (beautiful) tale of the genealogy of money provided by John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government (1690) is well known. Let us imagine you feel like working a lot in the month of October, and you collect many more apples than you and your family can eat during the rest of the year. Let us assume your neighbor, equally busy, has collected a great quantity of nuts. Why couldn’t you trade some of your apples for some of his nuts? The advantage of the nuts is that they can keep for several years, while the apples will rot within a few months. Now, if your neighbor’s neighbor has been led to collect colorful shells during his long walks on the beach, you may want to trade some of your apples and nuts for a few beautiful shells, which will not decay in your (or your children’s) lifetime. And if someone happens to find silver or gold more appealing than shells, why should we prevent anyone from trading nuts for silver, and apples for gold? And if someone really loves piling up nuggets of diamond upon mountains of gold, why should we restrain him or her from doing so? Hence the establishment of money and, more importantly, the legitimation of an unlimited accumulation of wealth among humans, says Locke.

With two provisos, however. The first is that nothing should go to waste. Pile up as much as you want, but don’t let it decay uselessly: trade it, so that another person can make good use of it – and everything will be fine. “Capital” thus becomes, not just a euphemism for money, but a moral justification for its endless accumulation, since it is endlessly used as it is invested and re-invested. The second proviso is that there should be “as much and as good left for others”. This latter condition is obviously trickier to establish and enforce: generations of political theorists have argued about its meaning, scope and stakes. Should one seize some of the properties of the (ultra) rich as soon (or as long) as some humans are deprived of the basic essentials? Should my neighbor’s needs limit my right to own? How is one to (dis)prove that there is not only “as much” but “as good” left for others?

At the beginning of the 21st century, Locke’s story ought to be read and reinterpreted within a somewhat displaced framework. The majority of Locke’s respondents have (implicitly) argued for greater freedom or for greater equality within the time-frame of a single generation. My accumulation of wealth was questioned in light of my neighbor’s needs. What happens if one brings into the picture my (or my neighbor’s) great-great-granddaughters?

Such a trans-generational reframing was prepared, many years ago, by the de-colonialist interpreters of Locke. They stressed how much this tale of apples, nuts and shells depended upon the premise that “all the World was America” (for the white man, around 1680): an unpopulated, virtually limitless expanse of resources that could be appropriated, exploited and extracted without any worry about the consequences of such extractions, or about the sustainability of its exploitation. Money – i.e. silver and gold, but also bank notes and financial shares, as their modern formats were invented in the same period – built its hegemony over social, temporal and ecological blinders, excluding not only the poor, but also great-great-granddaughters (and our co-existing species).

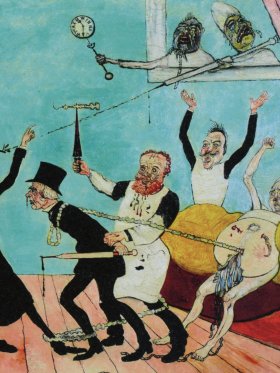

Ours is not so much the age of the Anthropocene (since only a minority of “humans” are to be blamed for the ecological havoc wrecking our planet) or of the Capitalocene (since the ussr did not take better care of its natural milieus than Western Europe or the usa), but more accurately of the Plantationocene2: the “Robinsonade” about apple pickers and shell collectors conveniently put a veil on the transformation of America (and soon the whole world) into an all-encompassing plantation, where slavery was officially (if not effectively) abolished a century and a half ago, but where the urge to replace biodiversity with monoculture, under the lure of profit based on economies of scale, remains as prevalent and destructive as it has ever been.

Hence a first lesson: in its function of appropriation and accumulation of value, money (in the guise of “capital”) should be distrusted as a measure of value, since it has been the major vector of an extractivist abuse of our natural milieus. As Bruno Latour eloquently argued, the main problem with monetary exchanges is to be located in their pretense to leave both parties “quits” (in French: quitte), once the agreed-upon amounts have changed hands3. The milieus we dwell in are strictly reduced to the countable resources our economic calculations identify in them. The value determined by money and other commercial transactions encompasses only a fraction of the multifaceted worth of any part of nature, but it erects this fraction to the status of the whole, since it treats this part of nature only according to its price. Extractivism can be defined as the exploitation of resources without due consideration for the remote consequences of their use, or for their conditions of sustainability. Locke only took into account the temporality of the decay of apples, nuts and shells, not the temporality of their renewability. His story of the genealogy and justification of money is proving to be dramatically ecocidal.

[...]

Share article