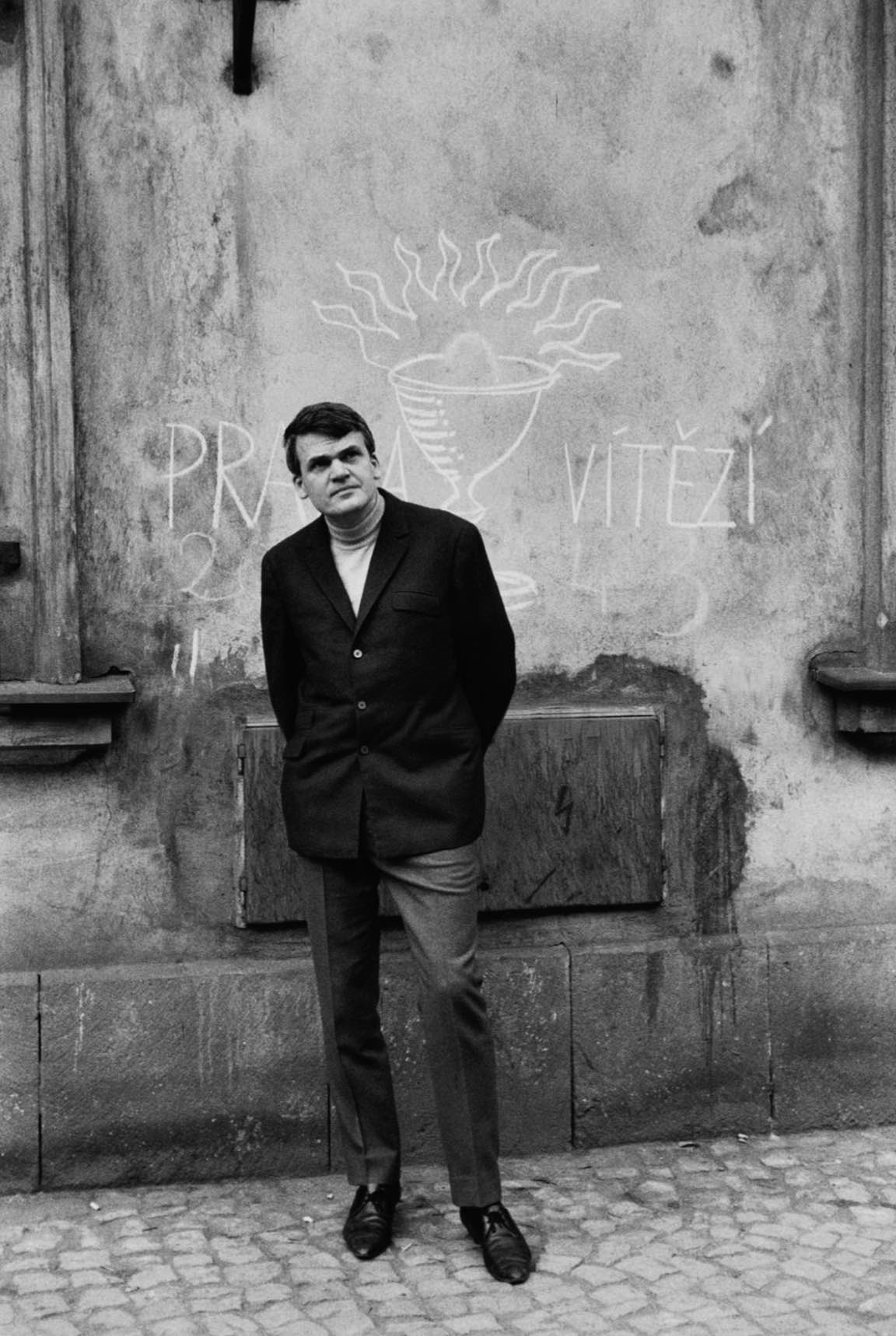

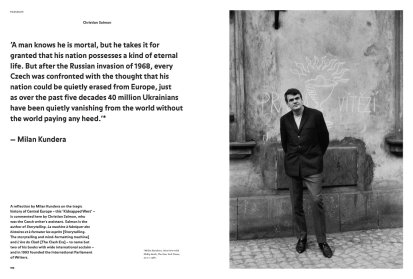

When I met Milan again in Paris, I was surprised to see that he was following the Greek news with such passion. He was impatient to hear what I had to say. With his instinct as a novelist, and not as a politician or ideologist, he had recognised in the Greek crisis the final link in the chain of revolts waged by small nations against the great empires, which for him had now assumed the abhorrent guise of the Brussels bureaucracy. The summons of Greek Prime Minister Tsipras to Brussels reminded him of the summons of President Dubček to Moscow in 1968.

I told him about my meeting with Ianis Varoufakis, the economy minister in the Siriza government, who had just resigned rather than abdicate alongside its Prime Minister Tsipras. Kundera called him ‘our hero’. I texted this to Ianis, who could barely believe what he was hearing. In this war of narratives, which mobilised the European elites against him, the support of a writer like Kundera was like manna from heaven. In his speeches, he spoke of ‘our Athens Spring’, associating it with the Prague Spring.

In his article ‘A Kidnapped West’, Kundera developed an existential phenomenology of small nations: ‘A small nation is a nation whose very existence can be placed in question at any moment; a nation that can disappear, and knows it.’ The thing that small nations have in common is not an identity or a language, but an experience of weakness when faced with the great empires surrounding them. Not a single exclusive belonging, but a similar experience of fragility and troubled existence – an experience reflected in the great Central European novels. Indeed, the small nations confronted with great empires are the nations that are most compelled to problematise their collective existence. That is why the questions of the state’s and the individual’s sovereignty, of the relation to the Other, to language, to History – all the great philosophical questions of the twentieth century examined by linguistics, psychoanalysis and the novels of Musil, Broch and Kafka – encountered their chosen territory in Central Europe.

Share article