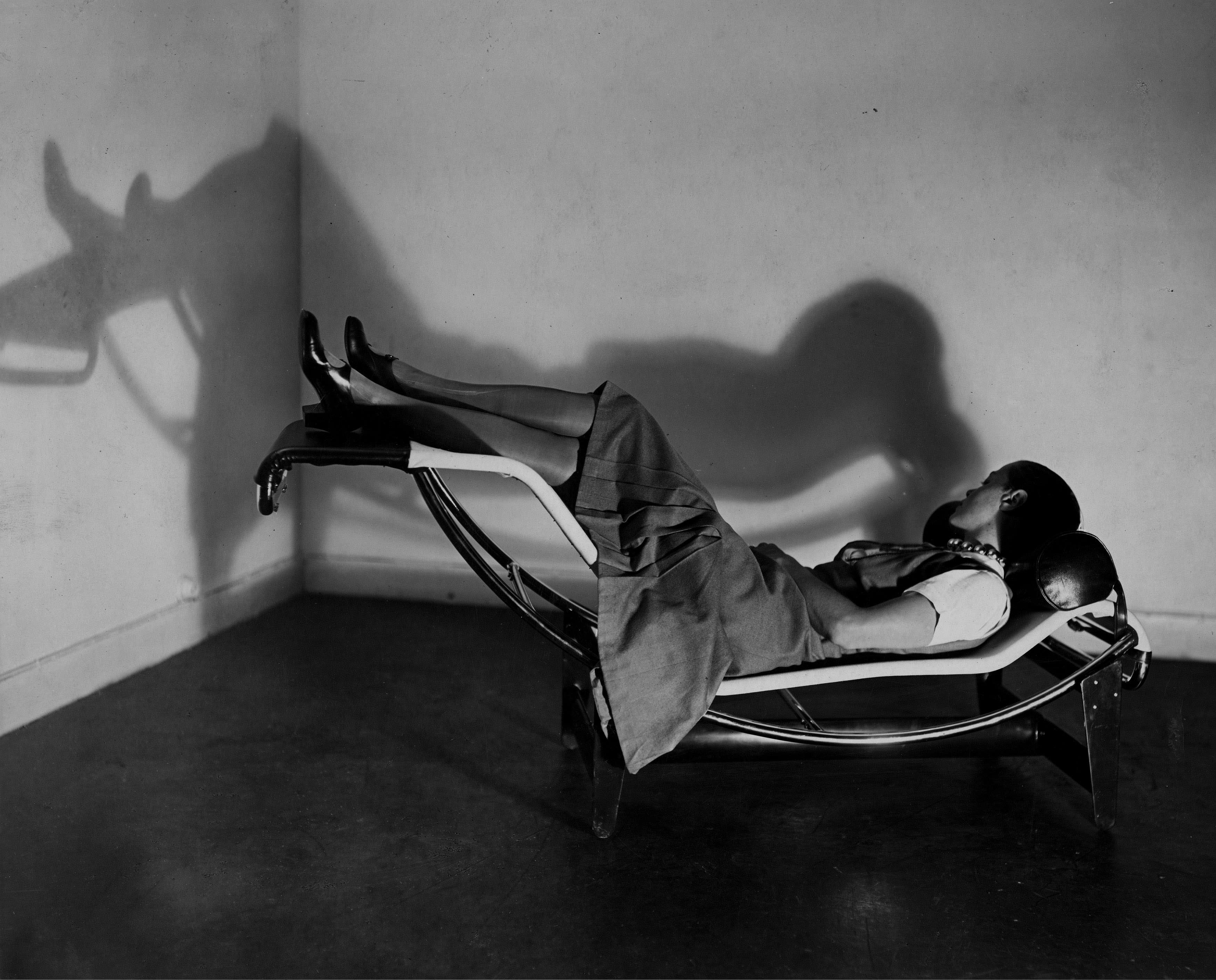

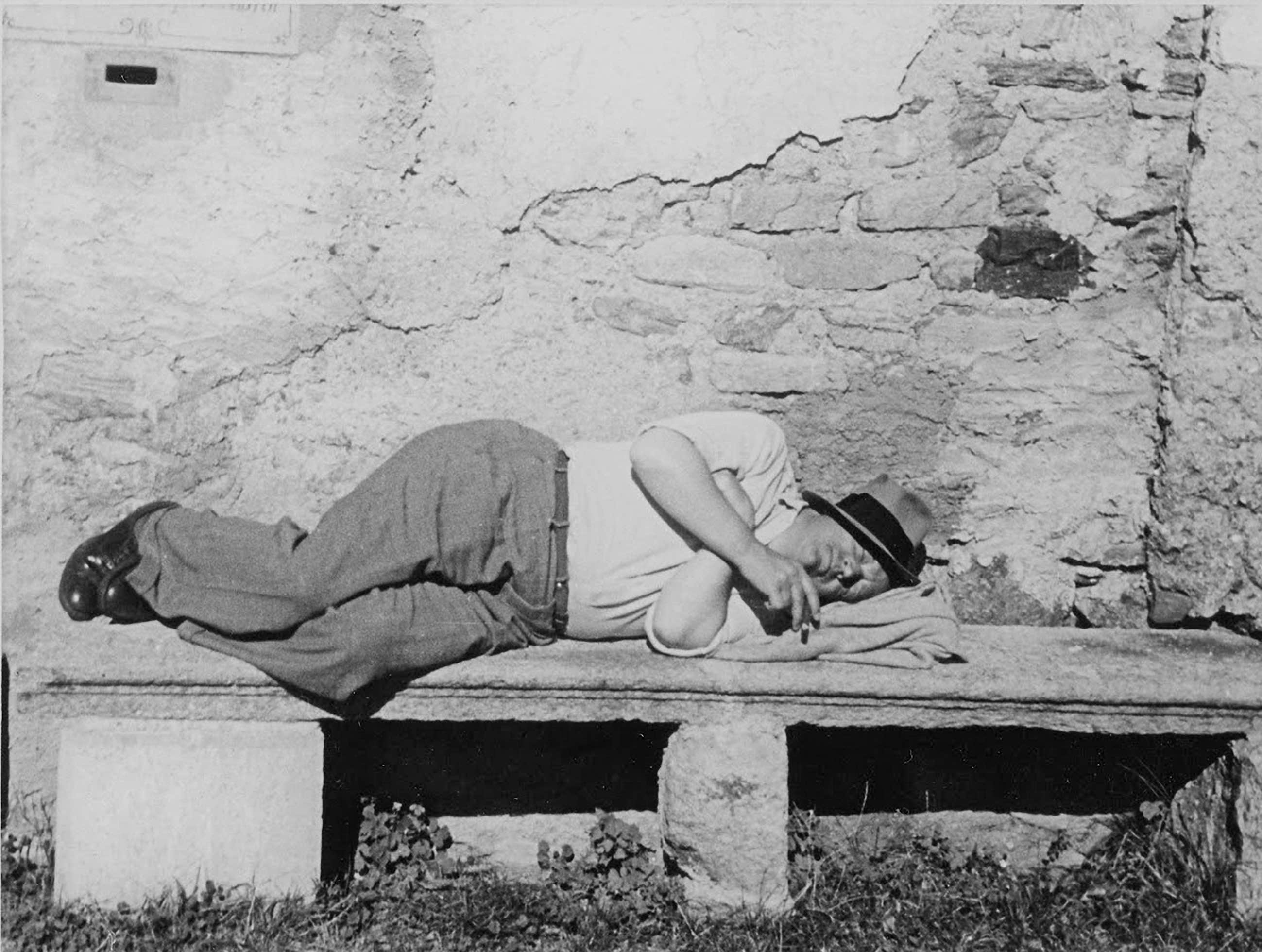

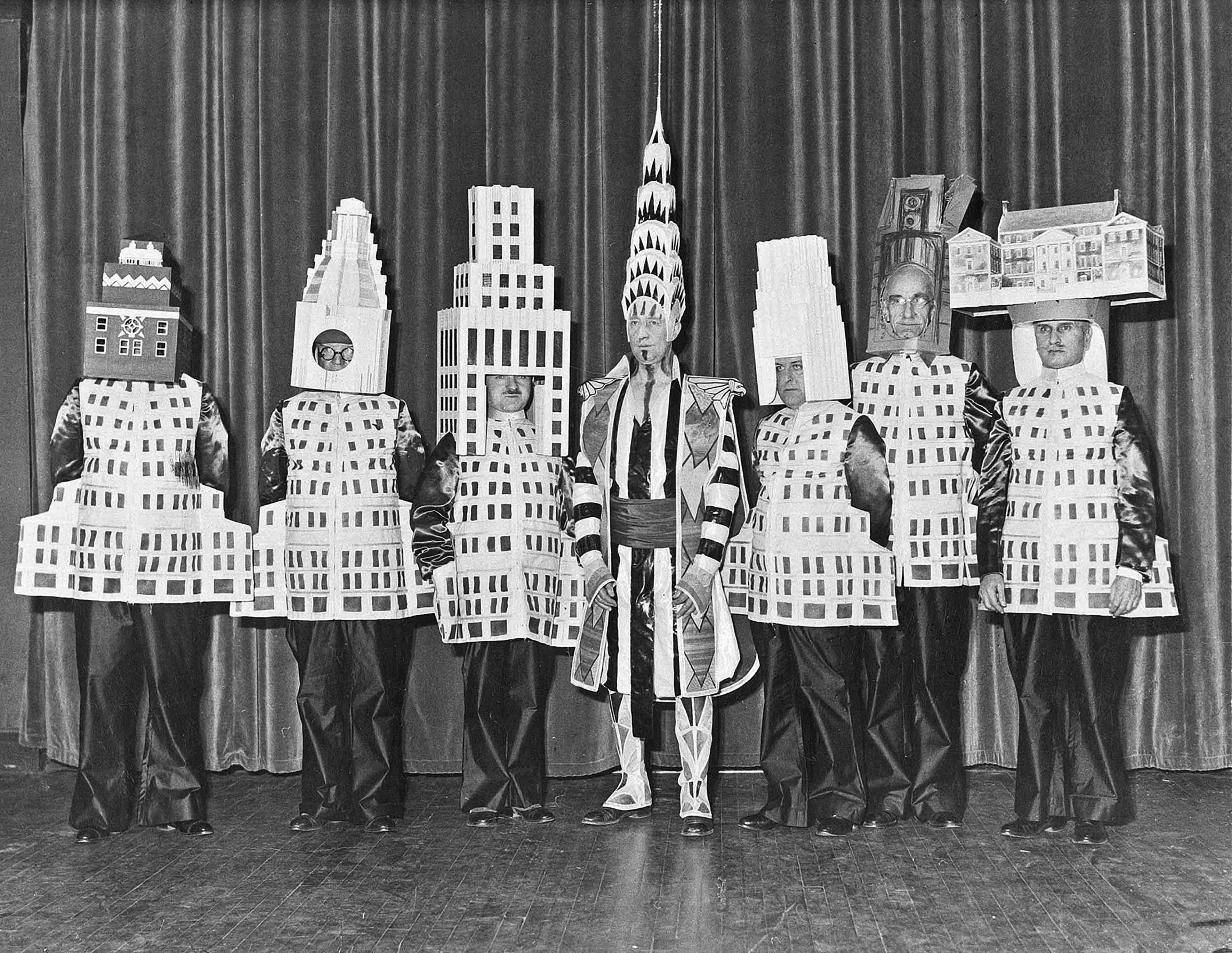

Bearing in mind Benjamin’s passage, so fruitful and varied in suggestions of critical thought, the idea that architecture was never useless is resumed (and reopened) in this edition of Electra, by the famous architect and curator Mark Wigley, in an original essay on idle architecture and the architecture of idleness. This text can be read in the dossier, dedicated to ‘Leisure and Idleness’.

Today it is evident that since the first half of the 20th century, the regimes of leisure and their relationship with the regimes of work, have gone through many changes. These economic, social and cultural transformations that have taken place and will continue to take place have deeply altered the nature of leisure, in its values, practices, modalities and meanings. Today, the times and spaces of leisure (and also of work) are very different from what they were in previous centuries.

This radical mutation institutes a new type of vision and administration of time, arising as one of the traits that help us draw the profile of ‘our great epoch’, as we have called the time we live in, borrowing Karl Kraus’s words and making his irony our own.

As one of our slogans says, Electra is ‘a magazine that is read and seen’. But it is also a magazine that reads and sees the world, and what makes and unmakes it.

It is often by ‘reading and seeing’ what is projected and built that we can extract an image from the world. This image governs the discourse that we project onto the world and build upon.

We could even defend that architecture is not only its theory and practice, since it is a cause and effect of many other things and a mobile mirror that reflects them. We associate a third notion with it and what it represents – themata (singular: thema). It was conceived and used by Gerald Holton, a North-American physicist, professor at Harvard University and historian of science, who is also a researcher with an in-depth knowledge of Albert Einstein’s work and archive.

Using this notion in architecture – and adjusting its meaning –, this word can refer to conceptions, references, methods, perceptions and terms that influence or condition the architects’ individual or collective activity. The themata can have a significant influence on the way we think, feel and act, establishing guidelines or defining polarisations that rule over the activity (research, creation, project, construction) developed by an architect or a community of architects, in a given time, place or environment.

Representing values and beliefs, generating attraction and aversion, promoting convictions and prejudices, whether aesthetic, technical, stylistic, artistic, sociological, political or religious, the themata are almost always unconscious or involuntary. They are almost never made explicit in architecture conferences, publications or exhibitions, but they influence and strongly condition the theoretical and practical activity of architecture, interfering both in the creation of one’s own theories and in the reaction (of acceptance or rejection) to other people’s proposals or solutions, whether conceptual or practical.

As João Barbosa, a researcher in philosophy of science, explains in his article about themata and paradigms, the themata are simultaneously intellectual and emotional, subjective and objective, serving as guides, orders, instructions, predispositions, preferences, beliefs, memories, attractions, prescriptions. They are persistent motifs, linking architecture to several disciplines, its past history and its present context and that of others.

As this researcher further mentions, the themata are prone to cycles of rise and fall, affirmation and concealment. They are present in several domains of knowledge and culture. They touch on Jung’s collective unconscious and Foucault’s episteme. They have a long life and a transversal, and even universal, vocation. They often work within a common cultural framework, whether alone, in dialectical pairs of antitheses (thema / antithema) – for instance, the fixed-mobile or dream-reality dyads – or in triads, such as greater-equal-less.

The same thema can be identified in disciplines as diverse as architecture, psychology, literature, sciences or visual arts. For example, symmetry is a recurring and essential topic in architecture, physics, mathematics and visual arts. Another example: harmony is fundamental in architecture, health, visual and decorative arts, music, psychology, religion and politics.

After the Romantic period, it is not possible to speak about architecture and the imaginary that corresponds to it without also speaking of the dream that ferments within it like wine. We just have to remember the oneiric and daring castles commissioned by King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Fernando Pessoa, who Eduardo Lourenço called ‘the King of our Bavaria’, asked in The Book of Disquiet this melodic and melancholic question: ‘And what divine substance constitutes the castles that are not of sand?’

Throughout the history of literature, many writers have turned architecture into one of the fundamental aspects of their works. In 2014, one of Cerisy’s well-known conferences was dedicated to ‘Architecture and Literature’.

There have been those who, with excessive voluntarism and exaggerated simplicity, have distinguished and classified writers into two categories: writers of space and writers of time. In any case, in the works of many 20th century writers architecture arises as a fundamental topos.

Among others, we could mention Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Virginia Woolf, André Gide, Louis Aragon, Jorge Luis Borges, Julien Gracq, Marguerite Yourcenar, Georges Perec, Julio Cortázar, Italo Calvino, Michel Tournier, José Saramago, Yukio Mishima and Bret Easton Ellis.

Surprisingly, in one of the Six Memos for the Next Millennium Italo Calvino speaks about his literary work as an architect would speak about his architectural work, although using a different terminology:

Share article