Heritage and transmission, experience and discovery, tradition and innovation, individual and social, pleasure and sin, necessity and waste, hunger and abundance, identity and alterity, food is culture and cult. We eat and we savour what we eat. We eat and we talk about what we eat. We eat and we want to know what we are eating. Sabores (flavours) and saberes (knowledge) have become inseparable through the similarity in sounds and the attraction of the senses. We travel to eat. Restaurants are places of veneration and liturgy. Chefs are priests, magicians, heroes, stars, and sometimes martyrs. Food – and all that surrounds it – is an art, a field of knowledge, a discourse, a fashion. It is a cultural process, an anthropological object, an ecological theme, a philosophical topic, a political issue.

At the same time as food is glorified, our obsession with eternal youth and with the body where this youth is exhibited (the theme of the dossier of Electra 5) leads to diets (or attempted diets) and the regimes in which they are followed as an ever-present horizon of our lives and of our deaths. More than ever, and better than ever before, we know that food can be health and sickness.

Nourishment becomes food when nature becomes culture, and one is to the other as sex is to sexuality. Nourishment and food divide, distinguish and differentiate continents, regions, countries, social classes, religious communities, cultural groups, generations and peoples. Food has a history and a geography, an anthropology and a semantics.

Words beginning with the letter ‘R’ are now inextricably related to the food that we eat. We talk of reviving, recreating, reinventing, remaking, replacing, reproducing, reworking, rethinking, and reimagining. Only the word fusion doesn’t start with an R. In food, memory is as fundamental an ingredient as any other.

The history of nourishment and of food – both near and distant, in time and space – is a history that is now made and remade until we see ourselves in it or are estranged from it, something that we inherit and that, sometimes, we squander. A daily stream of books is published telling us what food was and how it evolved, what it represented and what it provoked. Food is an indicator, a sign, symptom, demonstration, proof. Revisions join hands with reiterations, discoveries accompany surprises.

And so, when we now look back upon Greek antiquity, to see how life was lived then, we are often astonished by what we see. This surprise emerges, for example, when we try to discover the nature, in that world that appears to have been the birthplace of everything, of each individual’s relationship with him or herself and with others – and of the theories and practices through which they were expressed and given meaning.

In that search for the precepts, recommendations and warnings that configured the various possibilities of an ethics of life and an aesthetics of existence, observing what was called ‘care for the self’ and which some now call ‘self-techniques’, one of the discoveries that may amaze us most is the revelation that, for the Greeks, food was more important than sexuality.

Greek culture and society, as expressed through their systems of moral values and codes of individual conduct, their ideas about pleasure and sensibility about its use, paid more attention to food – and to the fasts that for some were associated with it – than to issues of sexuality. It should be noted that these value systems and codes of conduct weren’t intended to straitjacket everyone into homogeneity but to create personal choices suggested by philosophical schools. In stark contrast to the norms of permission and prohibition imposed by monotheistic religions, these choices were plural and distinct from one another, even if there were certain common rules, tendencies, and prohibitions.

This Greek hierarchy of theoretical and practical moral preoccupations, in which food ranked above sexuality, lasted into the early Christian era. Accordingly, the rules of monastic life reveal a great and overriding concern with nourishment and the appetites it engendered (gluttony). In the Middle Ages, a slow change took place and, with the increasing attention paid to sexuality, there was a kind of balancing out of the two preoccupations. It was only in the seventeenth century that the issue of sexuality started to become more prominent – a tendency that has been increasing ever since.

However, and even with this later prevalence of rulings and prohibitions regarding sex, the attention paid to food and to dietary behaviour remained part of the cultural landscape of various epochs, its presence and visibility ebbing and flowing over successive periods, as revealed by countless works of religion, philosophy, literature, the arts, the sciences, morality and law.

In the sixteenth century, an age of great change, Rabelais sang of (or pretended to sing of) the ‘science of the mouth’ and the ‘divine bottle’, inventing the Gastrolaters, who do not work or do anything, for fear of ‘offending or lessening their paunch’. They venerate the god Gaster, to whom they make sacrifices of products and dishes, a vast list that is recounted in meticulous detail. In Gargantua and Pantagruel the writer, who was a monk, a doctor and a professor of anatomy, brought together a craving for knowledge and a craving for flavour, mental and physical imagination, intellectual and sensual greed, imaginative abundance and verbal exuberance, seriousness and satire, stylistic fecundity and literary farce. Thanks to him, Pantagruel became not only a proper noun but also a common noun (in French) and an adjective (pantagruelian), much used over the centuries. Rabelais’ century was also the century of Bruegel and of his paintings of peasants eating and drinking as they celebrated their joyful weddings.

As the sixteenth century drew to a close, Michel de Montaigne dedicated a number of pages of his celebrated ‘Essays’ to food and to nourishment, discussing the experience and what it teaches us, taste and the way it changes, smells and their messages, the selection of foodstuffs, the sensations of appetite, the pursuit of pleasure, precautions and excesses, fasting and satiety, the fundaments of health and the causes of disease, medical prescriptions and their abuse, habits and timetables, the teachings of nature, conviviality at the table, harmony of body and mind, and wisdom and meditation. For Montaigne, ensuring happiness entailed taking as much care over food as over life.

The century that gave us Rabelais and Montaigne also gave us Luís de Camões and his evocations of meals and banquets, menus and delicacies. Evocations that have since inspired menus that faithfully reflect the poet’s words, based on assiduous research of the culinary products and eating habits of the period, filling gaps and compensating for ignorance with imagination in modern recreations of dishes from that distant age when Portuguese ships brought home what had never been tasted before.

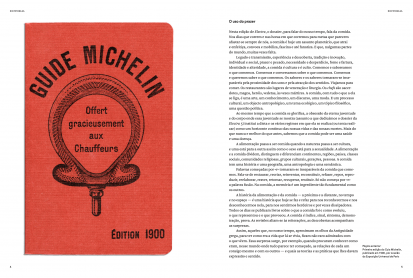

The history of gastronomy in Europe is French-speaking. Although the word gastronomie was invented in 1801 by the poet and humourist Joseph Berchoux as the title of a playful poem, the birth and development of the art to which it refers came long before. In 1651, halfway through the ‘Grand Siècle’, Le Cuisinier François by François Pierre de La Varenne, chef to the Marquis d’Uxelles, marked the shift from medieval cookery to the grand tradition of modern French cookery. This was a time of a variety of changes in food: from heavily seasoned dishes to the discovery of the natural flavour of products. The book was a revolution, and set out terminology and codified principles, rules and recipes that are still recognisable and palatable today. Some of his ideas on food have been passed down to our own age, or have been rediscovered. In the paintings of that period, such as Vermeer’s The Milkmaid, or Josefa de Óbidos’s still lifes, food seems to tell us secrets.

The transformations of the Enlightenment led – so long ago! – to a nouvelle cuisine. In 1735 Le cuisinier moderne was published by Vincent La Chapelle, who had been chef to various courts, including that of King John V of Portugal. Some years later, François Marin wrote Les dons de Comus (1739), stating in the preface,

Share article