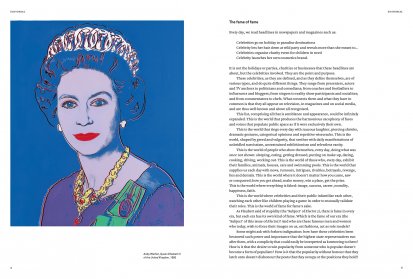

These celebrities, as they are defined, and as they define themselves, are of various types, and do quite different things. They range from presenters, actors and TV anchors to politicians and comedians; from coaches and footballers to influencers and bloggers; from singers to reality show participants and socialites; and from commentators to chefs. What connects them and what they have in common is that they all appear on television, in magazines and on social media, and are thus well-known and above all recognised.

This list, comprising all that is semblance and appearance, could be infinitely expanded. This is the world that produces the harmonious cacophony of faces and voices that populate public space as if it were exclusively their own.

This is the world that rings every day with raucous laughter, piercing shrieks, dramatic gestures, categorical opinions and repetitive wisecracks. This is the world, shaped by greed and vulgarity, that seethes with daily manifestations of unbridled narcissism, unrestrained exhibitionism and relentless vanity.

This is the world of people who show themselves, every day, doing what was once not shown: sleeping, eating, getting dressed, putting on make-up, dating, cooking, driving, working out. This is the world of those who, every day, exhibit their families, animals, houses, cars and swimming pools. This is the world that supplies us each day with news, rumours, intrigues, rivalries, betrayals, revenge, lies and denials. This is the world where it doesn’t matter how you came, saw or conquered; how you get ahead, make money, win a place, get the prize. This is the world where everything is faked: image, success, career, morality, happiness, faith.

This is the world where celebrities and their public infantilise each other, watching each other like children playing a game in order to mutually validate their roles. This is the world of fame for fame’s sake.

As Flaubert said of stupidity (the ‘Subject’ of Electra 2), there is fame in every era, but each era has its own kind of fame. Which is the fame of our era (the ‘Subject’ of this issue of Electra)? And who are these famous men and women who today, wish to force their images on us, set fashions, act as role models?

Some might ask with forlorn indignation: how have these celebrities been bestowed such power and importance that the highest state representatives run after them, with a complicity that could easily be interpreted as kowtowing to them? How is it that the desire to win popularity from someone who is popular doesn’t become a form of populism? How is it that the popularity without honour that they latch onto doesn’t dishonour the posts that they occupy or the positions they hold?

How is it possible that our era and our world have allowed themselves to be represented by these figures who turn mediocrity into an advantage? How is it possible that this vulgar fame has become the aura that thrills our age, the crank that raises our world aloft, the elevator that takes us to the very top of the social tower?

If fame was once the endorsement of superiority, the authentication of greatness and the attestation of glory, how is it that we have replaced superiority with inferiority, greatness with smallness, and glory with a failure to earn it?

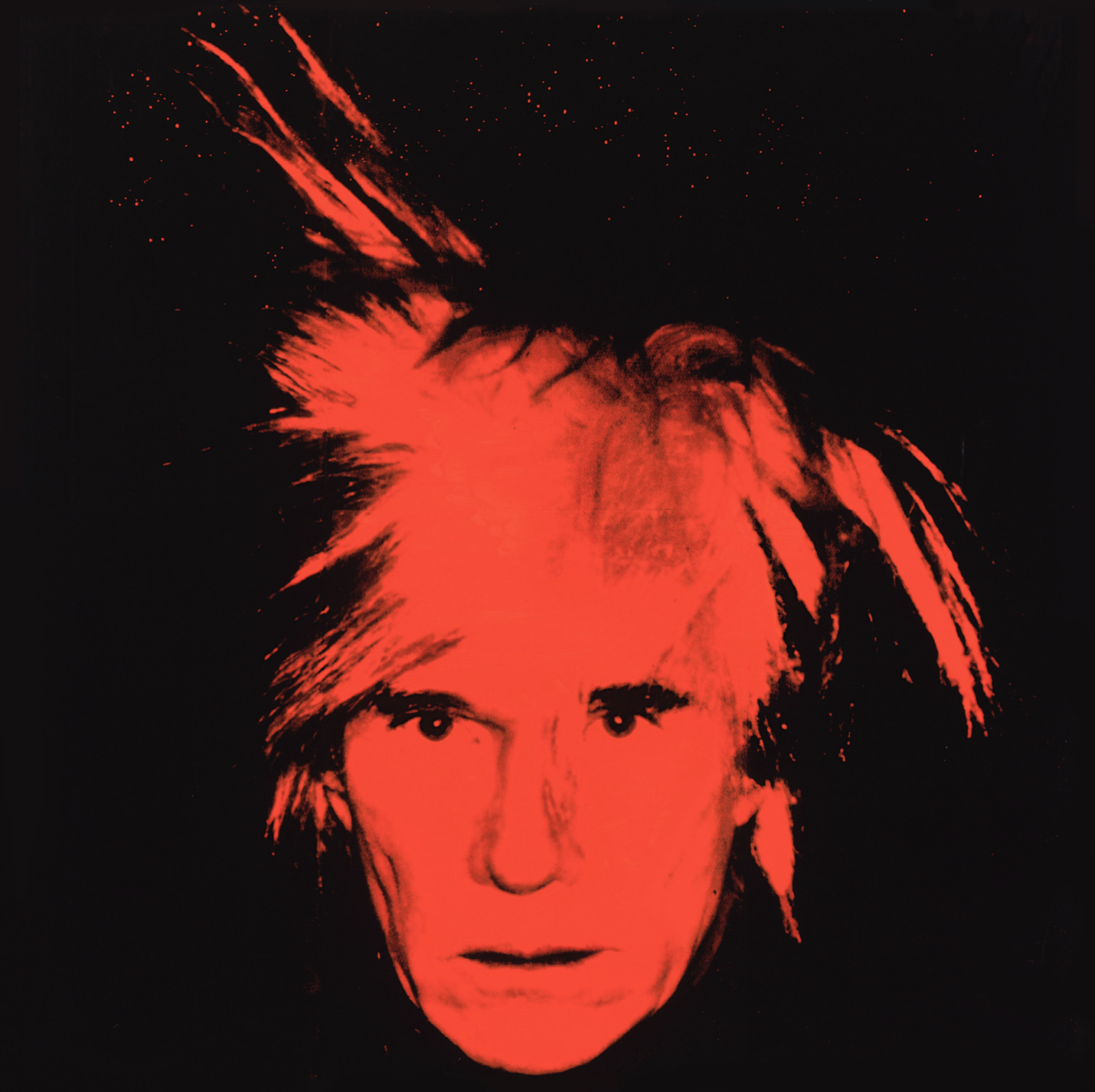

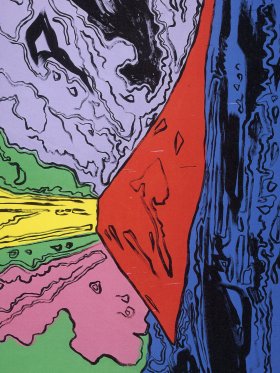

Andy Warhol was timid: when he imagined the moment in which we would all have our fifteen minutes of fame, he didn’t imagine that some would have not fifteen, but fifteen thousand or even fifteen million minutes of such easy fame.

There are those, nevertheless, who see in all this an inevitable democratisation and egalitarian levelling that, in mass culture and the society of the spectacle, puts an end to the separation between high and low culture, between the elite and the common people, between the privileged and everyday mortals. And so, the worldwide middle class and the global petit bourgeoisie are the foothills from which the mountain of this new fame rises vigorously and vengefully.

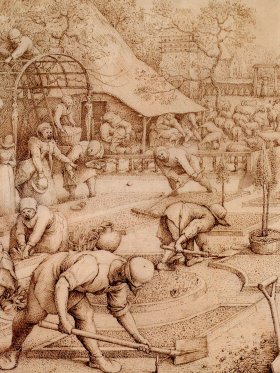

We know that the desire to be famous has been present in every era. Ever since man perceived himself as man (or maybe even before), he has wanted to be known and celebrated, proclaimed and recognised.

Celebrity is born of myth, and it clings on to that myth, growing on it as ivy grows on walls. The first great celebrities of the west, with a beauty formed of divine splendour and animal danger, were created by the mythical imagination: Helen of Troy, daughter of Zeus and Leda, who provoked conflicts, wars and deaths; Achilles the weak-heeled, son of Peleus and Thetis, friend of Patroclus and hero of the Iliad; and Ulysses, son of Laertes and Anticlea, King of Ithaca and cunning hero of the Odyssey. Jorge Luis Borges said that the Iliad and the Odyssey live on in the human heart because they speak of a war and a journey – and life is a war and a journey.

Fame and legend were bestowed on these founding figures by Homer, whose own legend and fame were founded on a shadowy, uncertain and mythical existence. Then came Herostratus, whom Fernando Pessoa used as the title of a text in which he pondered celebrity, genius and immortality. Over 2,400 years ago, the young Herostratus set fire to one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. His deranged and successful plan to ignite this blaze was for people to talk about him, thus bringing him renown and immortality.

The history of fame and celebrity is one of the most revealing of the many stories and counter-stories that make up human history. It is a mirage that traverses the long mirrored corridors of the centuries, where humans stare at themselves with an avid and anxious gaze.

In Histoire de la célébrité [History of Celebrity], – echoing the theories of the anthropologist, historian and philosopher René Girard – Georges Minois writes about mimetic desire, depicting the subject-mediator-object triangle:

Share article