the covid-19 crisis reveals the stratification of work

Economist, essayist and founder in 2000 of the French journal Multitudes, Yann Moulier-Boutang reflects on the imminent changes to the nature and organisation of work resulting from the structural crisis affecting it and laid bare by the pandemic-related lockdown, in particular due to the spotlight now focused on the massive informal sector that highlights the necessary distinction between activity, labour and employment.

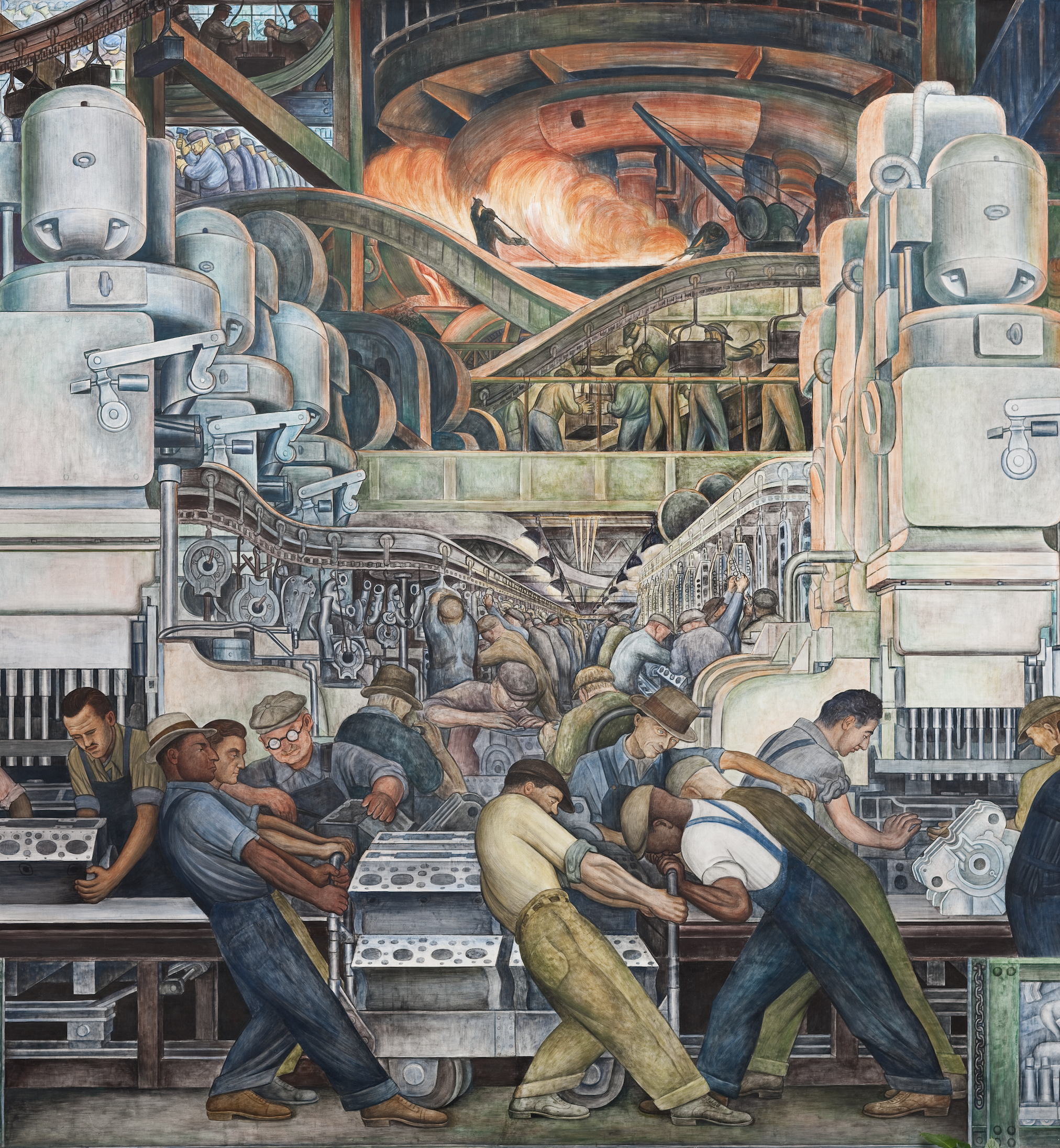

Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry, 1932-33

© Detroit Institute of Arts

The ‘suspension’ of much of the world’s economy as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic1 sparked an immediate question: what happens when it is over? Or, how will the economy bounce back? How will things change when the recovery comes? During this unprecedented crisis, a polarisation has become apparent, which can speedily be identified as a two-way split between 1) traditional waged employment, with guaranteed income alongside widespread innovations such as remote working, very substantial compensation for short-time working (in France, this is 84% of the former salary and as much as 100% for individuals undertaking vocational distance learning), credit facilities for businesses, and a moratorium on rents; and 2) the continuation and even boosting of those jobs that are ‘essential’ to ensure society’s survival, such as cleaning, transport, food supply, energy and above all the caring professions, for instance doctors and hospital workers.

But this polarisation would be incomplete without precarious workers and low-income groups involved in humble distribution functions, the casual workers and the unemployed who are not receiving benefits. Lock-down has shone a light on this informal sector.

The prospect of post-pandemic life has highlighted two problems: 1) the vulnerability of the most advanced economies to the relocation of key economic activities to China and India, for example the pharmaceutical industry and the production of medical and industrial equipment; 2) the impact on the economy of a large part of the working population being stuck at home, along with the growth of remote working. Two questions have been widely asked: 1) will the international division of labour linked to the global value chain be permanently changed? 2) will the nature and organisation of salaried work become radically different?

To answer these questions, they must be viewed in the context of the long-term employment situation and changes to the labour market that existed well before the pandemic. Before these points are developed, the situation may be summed up as a crisis in the three basic components of the labour market, which are a) traditional employment; b) informal work; c) unpaid work.

A preliminary observation on method2: distinguishing between the notions of traditional employment, informal work and unpaid work

As Fig. 1 indicates, work as a whole in its current form consists of three nested circles.

1) Activity that is not recognised as work and is unpaid: domestic work, any human occupation that contributes to the social and voluntary economy, but also – and this is new – all forms of human interaction on digital platforms. Proportionally, this is the most comprehensive circle in the diagram.

2) The circle representing work that may be formally remunerated or undeclared but is not recognised as employment: this includes casual, secondary and precarious work, as well as very new occupations that involve trading but are not institutionalised as jobs or employment.

3) And finally the smallest circle, which contains recognised, regulated employment, whether it be waged employment or self-employment.

Human activity depends on the state of development of the productive forces (culture, knowledge, skills, the accumulation of material means of production, as well as the nature of the population).

The delimitations that apply to the work grouping of the second circle depend both on whether the activity that becomes work is monetised and whether it is dependent on a boss: dependent work for others or for oneself. The worker may be dependent either on the person who commissioned and paid for the task, or on the market. However, this work does not necessarily imply a relationship of employment (therefore with an employer who takes on that role), or safeguards that are contractual or regulated by the welfare state (including those that protect the self-employed).

Allan Sekula, Volunteer on the edge, Isla Ciés, from Black Tide, 2002–03

© Allan Sekula Studio

Allan Sekula, Dockers unloading shipload of frozen fish from Argentina, Message in a Bottle, 1992–94

© Allan Sekula Studio

historical dynamics of the three spheres and the current crisis

The social behaviours that involve the flight from dependent work, as well as the struggle for unpaid activity to be recognised as paid work or for informal work to be recognised as protected employment, seek to make the institutional sphere of employment coincide as much as possible with paid work and to restrict the development of the most comprehensive sphere. This is a kind of golden age of widespread waged employment, as described by the sociologist Bernard Friot.3

Two phases are clearly documented between the fourteenth and twentieth centuries.

The first phase saw the emergence of free dependent work (as opposed to slavery, serfdom or labour hired for a fixed term), the creation of the indefinite term contract and recognition of the employee’s right to break such a contract unilaterally.4 The second phase saw the gradually developing association between paid (permanent) employment – which became the condition of 85% of the population – and the introduction of forms of protection against accidents at work and ill-health, together with the right to retirement. Initially provided by guilds and later by unions, this social protection was taken over by private insurers and then by the welfare state, which extended benefits to family dependents.

The golden age of the ‘Trente Glorieuses’ (1945-1975) descended into crisis for several reasons that will be examined later. The form taken by this crisis (see Fig. 1) translates into a very significant ballooning of the unpaid work sphere, a retrenchment of traditional employment and an expansion of informal work without protected status.

[...]

*Translated by Emma Mandley / Kennistranslations

Share article