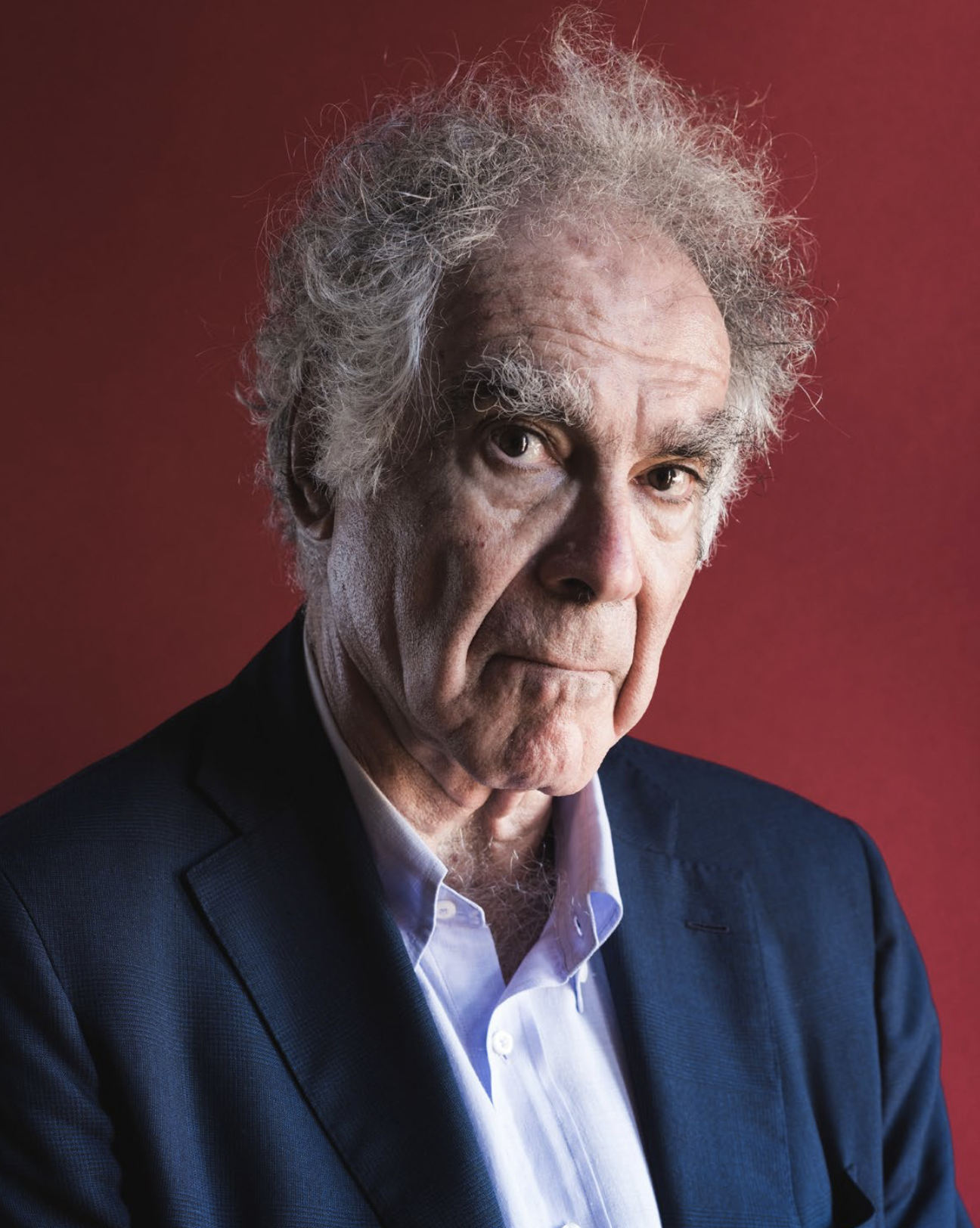

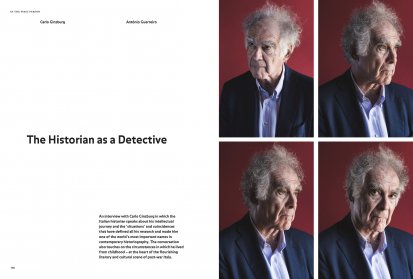

Carlo Ginzburg is among the most important contemporary historians. He is the author of a vast output that has revolutionised historiography, not only due to his use of sophisticated methodological and analytical instruments from other disciplines (anthropology, rhetoric, philology, narratology, etc.), turning the writing of history into a unified field, but also because he studies singular ‘cases’, facts and people (it would be more apt to call them ‘characters’). Eschewing the heroic tales of the powerful, outside of the horizon where traditional historiography finds its heroes and protagonists, these cases become exemplary and as universal as certain character novels. That is the case of Menocchio, a 16th-century Friulian miller. More cultured than most of his class, he suffered at the hands of the Inquisition and was eventually sentenced to death for heresy. Menocchio, whose real name was Domenico Scandela, is the ‘protagonist’ of one of Carlo Ginzburg’s master- pieces: Il formaggio e i vermi [The Cheese and the Worms], published in 1976. Similarly to many of his other books, this one can also be adequately described with an old phrase that is often abused: ‘It reads like a novel.’

The analytical processes introduced by ‘microhistory’, the name given to the historiographical current with which Ginzburg is indelibly associated and of which he has been the main theorist and practitioner, strongly encourage this narrative dimension and demand that special attention be given to the stylistic and rhetorical factor in the writing of history. It is not by chance that the author of Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath (1989) says in this interview that the path that brought him to microhistory was marked by two great figures of 20th-century literary studies: Leo Spitzer and Erich Auerbach, the author of Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Equally important to his task as a historian, where the tension between morphology and history is essential, is the influence (so to speak) of Aby Warburg, a singular art historian and founder of a ‘nameless science’.

But the immersion in a form of narrative writing that is aware of its processes (taken both from literature and cinema) and that presents a strong self-reflective component should also be understood through a biographical interpretation, reclaiming Carlo Ginzburg’s family history. Born in Turin in 1939, his mother was the writer Natalia Ginzburg (1916–1991), one of the great names of 20th-century Italian literature. His father, Leone Ginzburg (1909–1944), born in Odessa into a Jewish family that migrated to the West, first Berlin, later Turin, was a writer, professor, translator of Russian literature, founder of the Einaudi publishing house, and hero of the resistance against fascism. His academic career was interrupted when he refused to swear allegiance to the regime and he was eventually detained and tortured in prison, where he died in 1944, at the age of 39, as a consequence of the torture to which he had been submitted. Carlo was only five years old and in that little time he had experienced the fascist and anti-Semitic persecution of his family. Much later, as an internationally renowned historian, he understood that this circumstance had been behind his decision to study the Inquisition trials, especially the ones concerning witchcraft, when he was still a student at the University of Pisa. At a later stage, until 2010, he held a chair there, at the Scuola Normale Superiore (his academic path also included important moments at American universities). His integration into the literary world, which initially took place within his own family, continued as he moved in writers’ circles that included Italo Calvino and Cesare Pavese. More than an important Italian historian, Carlo Ginzburg is a central figure in the cultural and intellectual history of post-war Italy.

One of the main innovations of Carlo Ginzburg’s historiographical investigation is his focus on the popular culture, oral tradition, religious behaviours and customs of the ‘subaltern classes’ (a notion that dates back to Gramsci, another central influence on his intellectual path). He criticised an aristocratic view of culture, sometimes explicitly, which, from his perspective, has always limited the historian’s work. The question of the ‘task of the historian’ is implicit in all of his work and is developed in theoretical terms in some of his essays. When asked what it means to be a historian today, he answered: ‘First of all, one has to go against the current.’

Share article