It’s early September 2023 and I’m heading to La Goulette, in the port of Tunis, right next to where the ferries from Europe arrive. Within walking distance of the old Roman ruins of Carthage, it was a notorious Mediterranean pirate sanctuary during the Ottoman occupation. In the 19th century it was known as ‘la petite Sicile’ , home to a lively Jewish, Italian, and Maltese community. Claudia Cardinale was born there. Tonight, I’m watching a concert by Badiaa Bouhrizi, also known by her stage name Neysatu, a singer songwriter and composer known for her political resistance and for being a voice for social justice and freedom. Badiaa has won multiple awards and her first album Kahru Musiqa was released last year to critical acclaim. In the following days, we talk about music, politics, djinns and African identities.

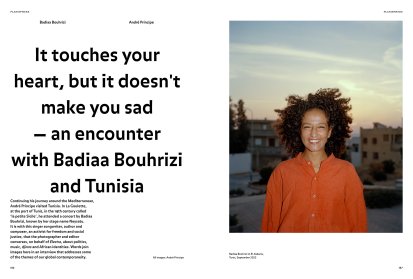

Continuing his journey around the Mediterranean, André Príncipe visited Tunisia. In La Goulette, at the port of Tunis, in the 19th century called ‘la petite Sicile’, he attended a concert by Badiaa Bouhrizi, known by her stage name Neysatu. It is with this singer songwriter, author and composer, an activist for freedom and social justice, that the photographer and editor converses, on behalf of Electra, about politics, music, djinns and African identities. Words join images here in an interview that addresses some of the themes of our global contemporaneity.

Badiaa Bouhrizi in El-Kabaria, Tunis, September 2023

ANDRÉ PRÍNCIPE Where and when were you born?

BADIAA BOUHRIZI I was born in Tunis on the 4th of October, 1979, a long time ago. I grew up in El-Kabaria, a very popular suburb for workers and public servants of ministers that had built their houses there. All around it were real ghettos. People lived in houses made of clay, zinc, metal sheets. I grew up around a lot of people. I felt privileged in comparison to others. Only later I understood I was actually poor. I’m the first child of five and I used to be a kind of genius in my neighbourhood because I was very good in school. My family comes from the northwest of Tunisia, a very rural and poor area, even though it is the main agricultural part of Tunisia. We feed Tunisia but we are hungry ourselves! Music is part of the family, both on my mum’s and dad’s side. All of them play these kinds of Bedouin instruments, for example, a kind of flute called Gasba. They were all musicians and singers.

AP What were you listening to when you were growing up?

BB In school we were singing lots of Fairuz1. In the entire Arab world, Fairuz is the morning songstress. All the radios in Tunisia play her from 7 to 10 a.m. Very clean in terms of lyrics for the kids. These are not love songs with a lot of lust…

Later, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd. It was the nineties. We all had the same mentality. Music was a symptom of our interests. We were very interested in philosophy, a political and poetic vision of life. Then I started being more into jazz, more into Africa. A group of friends went to a jazz festival in Tabarka, northwest Tunisia, on the sea. There was a jam every night and we played together; we had an amazing connection. Back in Tunis, we decided to create a band of absolute improvisation. This opened the door to feel free, to be confident on stage, in yourself and the connection with others. The feeling you have is more important than the aesthetics of what you’re going to play. You shouldn’t be trying to construct emotions that you don’t have. I finished high school and went to Tunis university. I was studying English literature and civilisation. Near the end of the second year, something happened. I was harassed on a tram. People on the tram were on his side! I remember just feeling something bitter inside. People were holding me, and he was free. That day I thought, ‘no more Tunisia. I need to go away.’ I’d had enough of being aggressed every day.

AP How old were you?

BB I was nineteen or twenty.

AP Was it your experience as a woman that made you want to leave?

BB More the realisation that I’d had enough of it. I had been in Paris for holidays and I had experienced feeling safe. Two years before that I had been accepted in La Sorbonne for English literature. I didn’t go at the time because I was in love and had decided to stay in Tunisia. When I got to France, I tried to go to music school. There was this left-wing university, Paris 8 Saint-Denis. But by the third year, I realised I didn’t want to be in musicology or teaching. I wanted to be in practice. I was playing music also, especially during the period at university. It was kind of part of the studies. Instead of training at home for the rhythms, we had batucada. You learn to read quickly, at 70 bpm2 and then at 100, 120, 140. It was a cool period. We would do all the jazz jams in Paris. At the end of 2007, I was again in love, so we moved to England and decided to do only music. I started living in Brixton, a Jamaican neighbourhood. By December, I already had a band of afrobeat jazz called Awalé; the name comes from an African game that you play moving little rocks from one hole to another, a mathematical game. We played in many festivals in England. I was singing in English, French and Arabic. There is a scene for that in London. We played live during the night, till 5 a.m.

AP How long did you stay in London?

BB Until the beginning of 2012. In 2010, my music started going round in Tunisian circles, through USB. Some songs were very political, so I used a pseudonym. I was talking about the hypocrisy of the government. Religious manipulation while oppressing religion. Selling the country to tourism. When I was a student in France and would come back to Tunisia, I saw how the police treated people. Beating ten-year-old poor kids doing nothing, just singing on a tram. In 2008, I played in a small festival we had. We did it on the beach of Kélibia. Musicians were playing for free, promoting it with a donkey going through the village.

The police brought a paper for everyone to write their name, identity number and to sign saying you wouldn’t get too drunk or use drugs. The real reason was quite clear. They just wanted to have the identities of everyone. I wrote another name! Two 4x4 of Secret Services were by the stage while we were playing. Around that time, the first revolt happened in the mining zones, in Gafsa Redeyef. There were protests, uprisings. For the first time since 1983 the police opened fire. A kid was killed. Hafnewy Maghzawy, his name was. This kid came from a very small village that is the epicentre of the mining production of phosphate. At that point, we were the fourth producer of phosphate in the world so there was a lot of pollution. People there have cancers. It’s a rocky and sandy place, one of the most miserable I have ever been to. He was 17 years old. He wasn’t even for a revolution but when there are no solutions, you’re hungry. The song is not documenting his assassination, more trying to imagine what was happening in his head. He put his head up, he talked, he was being oppressed. One verse is talking to policemen. I’m the daughter of a policeman. I know how we live. I know that we were poor. The fact that you raise your gun, and you take someone else’s life, it is an aberration. It’s not the reality that you would find in Carthage. I remember starting singing but my voice was just going away. At the festival, they asked me ‘please, nothing political.’ If there’s nothing political, I can’t sing anything! I told the organisers, who were my friends, that I was not going to sing anything political. But I did.

AP Did the police come out of their cars?

BB Nothing happened.

AP So, they were not listening. Or pretended they were not.

BB I had a revelation that night. Why, as an artist, should I be the voice? I was protected by too many eyes on me for the police to come. And I protect the public because they don’t need to say anything. They stay anonymous. They just clap and say ‘yeah’.

AP You’re protecting them, and they protect you.

BB Exactly. The audience is not saying the words. I liked that exchange of power. I felt powerful with it, and in the end, I played the gig in front of the police. I could see them from the balcony. And from that day, I couldn’t play in Tunis. Next time I played there was 2011, after the revolution.

[...]

Island in the Mediterranean, November 2022

Share article