According to the master of the second generation of the École des Annales and the theorist behind ‘long-term history’, or longue durée, and material civilisation:

History is made up of what continues within us; it reminds us of what we did not live, or imagines what we have lived, which consequently becomes even more ours. The great historian Fernand Braudel, in one of his Écrits sur l’histoire, states that great political and social upheavals urge us to think or rethink the Universe.

Alex Katz, Carnations 3, 2022 © Alex Katz / VAGA / ARS / SPA, Lisbon

From the turmoil of the great French Revolution, which for years wholly constituted the dramatic history of the world, was born the meditation of count Saint-Simon, and later of his inimical disciples, Augusto Comte, Proudhon, Karl Marx, who have not stopped tormenting the spirits and intellects of men ever since… A small example, closer to us: during the winter that followed the Franco-Prussian War of 1870−1871 there was no better witness than Jacob Burckhardt, secluded in his cherished University of Basel! Nonetheless, restlessness visits him, a need for great history pressures him. His lessons, during that semester, are about the French Revolution. As he states in a fair prophecy, it is only a first act, a lifting of the curtain, the initial instant of a new cycle, of a century of revolutions, destined to last… A truly endless century that will mark in red lines, both narrow Europe and the whole world.

By evoking the historian, art historian and philosopher of history Jacob Burckhardt, Braudel brings us the author of The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy, in whose work the face of power and the face of culture complement, observe and measure each other. These mercilessly mutual gazes take on a founding importance. The first part of his book on the Italian 14th and 15th centuries is entitled ‘The State as a Work of Art’. In the 20th century, the art critic, philosopher and media theorist Boris Groys published a book entitled The Total Art of Stalinism. There are great political events that become great events of thought and culture – and vice versa.

Revolutions, which turned time against itself, are some of those memorable events that follow their course through us and through what, from generation to generation, we make of them, of their memory delivered, received, contested and transfigured by the next generations. With these events and through these generations, the world has changed and the human gaze rests on that other-world. In order to recognise it, the human gaze must repudiate its old habit of observing so as to understand it.

This was the case of the American Revolution from 1765 to 1791, the French Revolution from 1789 to 1799, of which Braudel spoke, the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Cuban Revolution of 1959, and May '68. And, in Portugal, the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the Republican Revolution of 1910, and the Democratic Revolution of 25th April, 1974.

These great political convulsions, beyond the institutional breaks and the political, social and economic transformations that stemmed from them, gave rise to a different imagery and distinct symbolic systems, created new concepts, words, images and works of art, caused ethical fractures, produced aesthetic fancies, originated artistic metamorphoses, and engendered a cultural evolution. They changed customs, codes, signs and iconographies. They replaced sentences, forms, figures, forces, ghosts…

A famous maxim says that a revolution is not an invitation to dinner. But it was, and still is, an invitation to think, write, paint, draw, sculpt, compose, play, dance, photograph and film.

The 25th April 1974, the 50th anniversary of which will be celebrated in Portugal this year, has served as inspiration and motif for the creations of poets, novelists, playwrights, filmmakers, painters, sculptors, architects, musicians, and dancers throughout the last half century. Also, for the work of philosophers, historians, sociologists, legal experts, political scientists, and journalists. Everything that was done by them, in its multiplicity and variation, is part of a legacy that will last longer than us, thus adding a new heritage to the heritage of what happened, which was discontinuity and beginning, tear and break, enchantment and temptation, utopia and illusion, construction and destruction, drift and detour, hope and frustration, mirage and disenchantment, dream and reality.

This is a cultural legacy that is considered, assessed and renewed when the years that make up time are broken into intervals, like the milestones that existed on long Ancient Roman roads, deserving and prompting a more marked, distinguished, scrutinising and prospective commemoration.

On the 50th anniversary of 25th April, we see, hear and read – and there is in this a desire to return to the origin, the starting point, the blank page, the initial moment, as if it were the creation of a new world, or the invention of the new in the old world.

Therefore, it is propitious to give voice to those who went through the Revolution of 25th April and turned their experiences into a testimonial as tall as a landmark, as long-lasting as a classic.

We read what the writer Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen recounts in words written in an unpublished notebook, which are full of revelatory drive and primordial potency. This testimony also unveils the genesis of a poem that became a major symbol and the most quoted of the poems that celebrate this festive Portuguese revolution which put an end to a long dictatorship that had lasted almost half a century and seemed to have become natural, normal and perpetual.

The great poet noted:

On 25th April 1974, at 4:30 in the morning, a friend called and told us to turn on the radio because there was a revolution going on.

The room where we were listening to the radio had a glass door that overlooked the garden. As we saw the revolution advancing and forming itself, we saw the light of day growing and we felt like we were emerging from the dark and the opaque. It was more than a revolution to us; it was a resurrection. It was Easter. I saw an entire people inhabiting transparency. I saw crowds dancing in freedom.

Sometimes we would look at each other and ask: ‘are we dreaming’?

One day a friend said: ‘even if this revolution fails, even if everything should end in disaster, we have experienced this.’ Because, for us, 25th April was more than a political liberation, it was the liberation of life, the renewal of the world. During those days I wrote:

This is the dawn I expected –

the first day, whole and clean,

where we emerge from the night and the silence.

And free, we inhabit the substance of time

Before this, Sophia had written poems of resistance and accusation, opposition to and denouncement of the dictatorship, the colonial war and the scandal of its endless continuation. Afterwards she wrote poems of celebration, joy, admonition and warning about the revolution and its dangers, which, born from its centre, surrounded and sieged it like a ring that tightens. These poems, the ones from before and those after, rise beyond the circumstances that motivated them. They remain intact, in their verbal and poetic force, as well as current, in their moral and political teachings.

This is the reality, and will continue to be, since the words that compose them defend themselves and defend the poems against what could devalue them or render them useless. Sophia’s political poems are not made up of the dead words that serve overused commonplaces; they do not utter time-worn, propaganda-like slogans. She used to quote an African proverb from Burundi that states: ‘a word that is always on your lips becomes drool.’ The words of her political poems remain alive because they speak of life in politics and of politics in life:

We know that life is not one thing and poetry another. We know that politics is not one thing and poetry another.

We look for the coincidence of existence and essence. Looking for the entireness of being on earth is the quest of poetry.

She adds:

When the words of poetry do not serve politics, it is politics that should be corrected. The truth and essence of the revolution demand that poetry may always freely create its path.

It is important that we clearly understand that art is not a luxury or adornment. History shows us that the Palaeolithic man painted cave walls before he baked clay or knew how to plough the land. He painted to live. Because we are not just hounded animals fighting for survival.

And if politics should unalienate our political and economic lives, it is poetry that unalienates our consciousness.

Because it proposes to man the truth and the entireness of his being on earth, all poetry is revolutionary.

Therefore, the most efficient way for the poet to help a revolution is to be faithful to his poetry. Writing bad poetry saying that you are writing for the people is just a new way of exploiting the people.

Whoever is really committed to a better country and a better society fights for the truth of culture. Those who are complicit with mediocrity are the enemies of a better society, even if they proclaim high revolutionary principles. A revolution of quality is radically necessary for a real revolution.

Where there is no poetry, nothing real can be founded.

(Address to the 1st Conference of Portuguese Writers, May 1975)

We now read these words, as precise as geometry. They are full of rigour and alarm, vitality and vigour. Beside them, our poor political words of today resemble discoloured ghosts, without a face or a name.

For this reason, Sophia’s words constitute an accusation against our world and time, to which the great and exemplary questions that these words pose seem strange or incomprehensible, as if they were uttered in a distant language or written in an unknown alphabet. What world and time are these when talking about entireness and disalienation, about the revolution of quality and the search for the poetry that founds the real, seems to be something born from an anachronistic or meaningless urge?!

Nonetheless, the relationship – affinity, opposition, conflict, submission, insubordination – between politics and culture, politics and art, and politics and language is an omnipresent topic (or rather: a problem) in the intellectual and political history of modernity.

Walter Benjamin’s work is an inexhaustible and visionary testament to this. A few decades later, Milan Kundera’s books, founded on a diverse political and existential experience, also address this question with sharpness and sarcasm.

We cannot forget that the relationship between politics and words, which Sophia turned into an important motif of her poetic art and poetry, is a topic that comes from the Greeks (sophists, Plato, Aristotle) and later the Romans, but which became, with the French Revolution and the revolutions that followed, a constant and renewed motif of philosophical reflection and intellectual inquiry.

Seconding what we have said, George Steiner uses this topos to make a harsh diagnosis of our time and culture. In the well-known essay ‘The Retreat from the Word’ (1961), later collected in the book Language and Science, this professor and literary critic, who liked to be called a ‘master of reading’, tackles the disgraceful abuse and the violating violence exerted on language in and by totalitarian regimes (on this subject, there is a seminal book by Victor Klemperer, entitled The Language of the Third Reich). He also reflects, in those distant 1960s, on the breakdown of language operated by the demagogic and populist drives in free-market and consumer democracies.

Steiner states:

Surely there can be no doubt that the access to political and economic power of the semi-educated has brought with it a drastic reduction in the wealth and dignity of speech.

I have tried to show elsewhere, in reference to the condition of German speech under Nazism, what political bestiality and falsehood can make of language when the latter has been severed from the roots of moral and emotional life, when it has become ossified with clichés, unexamined definitions, and leftover words. What has happened to German is, however, happening less dramatically elsewhere. The language of mass media and advertisement in England and the United States, what passes for literacy in the average high school or the style of present political debate, are manifest proofs of a retreat from vitality and precision. The English spoken by Mr. Eisenhower during his press conferences, like that used to sell a new detergent, was intended neither to communicate the critical truths of national life nor to quicken the mind of the hearer. It was designed to evade or gloss over the demands of meaning.

Pierre Bonnard, Les œillets [Carnations], 1921 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Christie’s Images, London

This sombre reflection that the author of Real Presences and Grammars of Creation casts on the language of politics within democracies has become a prediction that tragically describes our time. Everything that he said, over six decades ago, has continued to acquire a disturbing and growing seriousness and can now be repeated, reiterated, restated, with increased shock and trepidation.

In his critical meditation, Steiner concludes that ‘whether it is the decline in the life-force of the language itself that helps bring on the cheapening and dissolution of moral and political values, or whether it is a decline in the vitality of the body politic that undermines the language’, both things contribute and converge to threaten language and impoverish it, cheapening human communication, cultural creation, critical thinking, rational reasoning, the representative bond, the credibility of politics – and promoting a new, growing, strangely tolerated, or even insolently flaunted and praised, illiteracy.

All we need today is to pay attention to the succession of comments and commentators in the public space and their blunt and rampant competition to secure their strident participation in the society of spectacle, to be certain of the sad prestige of ignorance and the indecorous benefits of unculture, and even blatant idiocy. And we are completely enlightened about the huge advantages of moral insufficiency and ethical depreciation.

What the French President Emmanuel Macron recently described, with apprehension and an ill-concealed feeling of guilt, as a ‘crisis of the democratic model’, is clearly present and evidently displayed in the language of politics, in the degradation visible in all of its settings, channels, devices and formats: from parliamentary tribunes to social media, from official speeches to TV debates, from media soundbites to propaganda-like slogans, from mass rallies to individualised podcasts, from election promises to fake news.

Electra has been paying close attention to these subjects since it views them as fundamental to a thorough and much needed diagnosis of the contemporary world. From the dossier that we devoted to the state of democracy to the one where we tackled journalism and the media, we have talked about this topic that is now revisited. Directly or indirectly, Sophia and Steiner also presciently addressed it in their reflections on the words of politics.

The dossier of this issue is devoted to the topic of excess, equally fundamental to understanding our ‘great age’.

In revolutions there are always excesses and the same is true of counter ‑revolutions. We have always seen this, and we have always known that it is part of their hypertrophic logic and hypertelic dynamic.

What we may not have noticed is that excess has also become the measure (or ‘unmeasure’) of contemporary democracies. We only need to look at the media-dominated public space that is produced in them to see excess and the excessive everywhere. Populisms are, above all, phenomena of verbal, emotional and communicational excess – and that is inseparable from their tirelessly predatory and aggressive drive. Coalescing with what the architect Mies van der Rohe said (‘less is more’), in populisms, excesses are flaws and more always becomes less.

Mimicking the chilling rise and seizure of power by totalitarianisms in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, the recent invasions of the Capitol, in the United States, and of the Congress, in Brazil, were preceded, encouraged, accompanied, confirmed and justified by an uninterrupted and endless flow of verbal excess. In this way, today the relationship between words and politics has gained a new and terrifying acuity, both dramatic and grotesque. This phenomenon – and what it is a symptom of – is also analysed in our dossier on excess.

In this issue, we present the interesting testimony of the Italian philosopher Donatella Di Cesare, where she recounts her experience of the Portuguese 25th April. And the work that we show, by Sónia Vaz Borges, Mónica de Miranda and Vânia Gala, who are representing Portugal in this year’s Venice Art Biennale, evokes colonialism, the fight for independence and decolonisation. To speak about this is still to speak – although from a different perspective – of the 25th April. These topics are also present in the interview with the philosopher Michael Hardt published in the ‘First Person’ section.

Emmanuel Levinas remarked that saying to someone, ‘after you’, thus giving them priority, represents one of the most sophisticated and thoughtful human gestures. It might also be one of the most democratic.

Such a gesture seems increasingly rare in a world where everyone wants to beat others, and everyone wants to win first place in everything. For them, the ‘after you’ is always replaced by ‘before you’ or even ‘without you’…

Similar to the gesture of letting someone go before you is letting them speak before you, listening to them, understanding them – and, fulfilling a supreme form of delicate dedication, questioning or challenging them, if that is the case. This is what we have done with Braudel, Sophia and Steiner in this Editorial.

To speak of revolution, both in politics and language, in the fragile democracies of today, we have given prominence to those who spoke about it with such prescience and wisdom, that we should listen to and reflect on what they said in a time that foreshadowed our own.

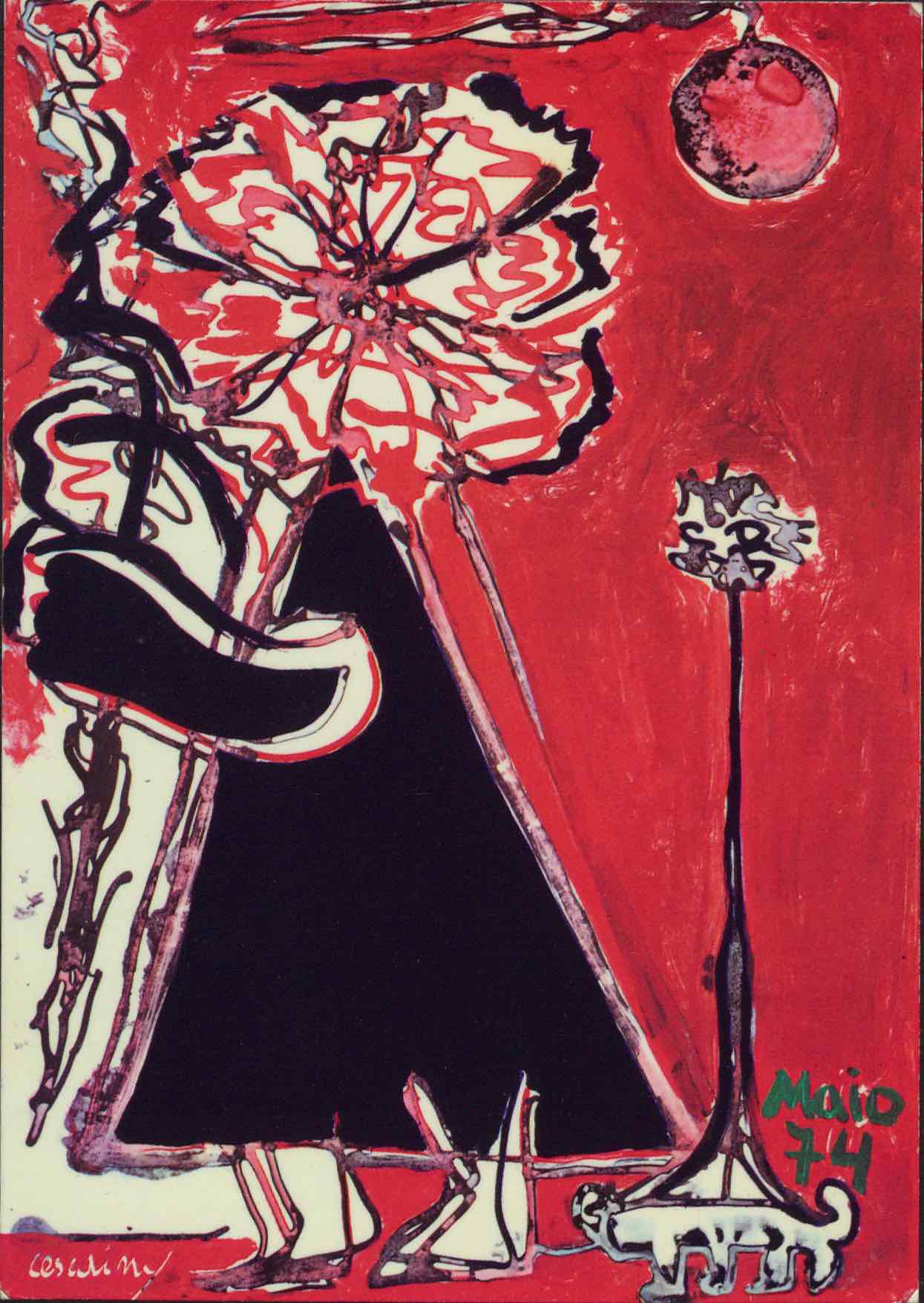

On the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution (such a visual and iconic image that it has been taken up by many painters and illustrators), amidst so many uncertainties and threats, so many challenges and dangers, we find in the words of the writers, in the images of the visual artists and in the sounds of the musicians that it inspired, a memory, at the same time celebratory, testimonial and critical, which allows history to continue and be passed on to those who one day, which is never that distant, will say: ‘after you.’

© Mário Cesariny / Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon

Share article