It is at this point that the fourth course on the menu, ‘The Mess’, is served. The film continues in a crescendo that is more gore than horror, and where the chef’s metaphysical observations – the pulse of nature, the taste of the ocean, the breath of the world, and so on – do not point so much to inner peace, and much less social harmony, as towards violence and death. Our sense of taste, it is suggested, is the beginning and end of everything.

This is a perfect allegory, exaggerated and caricatured, of that which is taking place today in the world of haute cuisine, a world which has been distinguished in recent decades with stratospheric honours and burdens, especially in the media. On the one hand, we have the increasingly exasperated gastronomic quest for novelty and surprise, the race for ‘wow’ at any cost, with legions of admirers ready to be amazed by yet another chef’s gimmick; on the other, there is the growing feeling that none of this is a celebration of the discerning palate but its exact opposite: a form of spectacularisation of food that ultimately serves to annul it, to erase the healthy pleasures of eating in the name of intellectualism as an end in itself. At the beginning of the film, the chef exhorts his diners not to eat but to ‘taste, savour, relish’ every morsel they place in their mouths; however, what he offers them is not nutritional sustenance – to just eat (a term he uses for blatant denigration) –, but what he calls ‘a mystery’, i.e. a conceptual tasting in which – as we will learn – the diners are themselves transformed into ingredients. In the end, a purifying conflagration takes over the whole system: the kitchen brigade, the customers, the critic, the magazine editor, the restaurant building itself, its owners. Gastromania, if you want to call it that, would seem doomed to end badly.

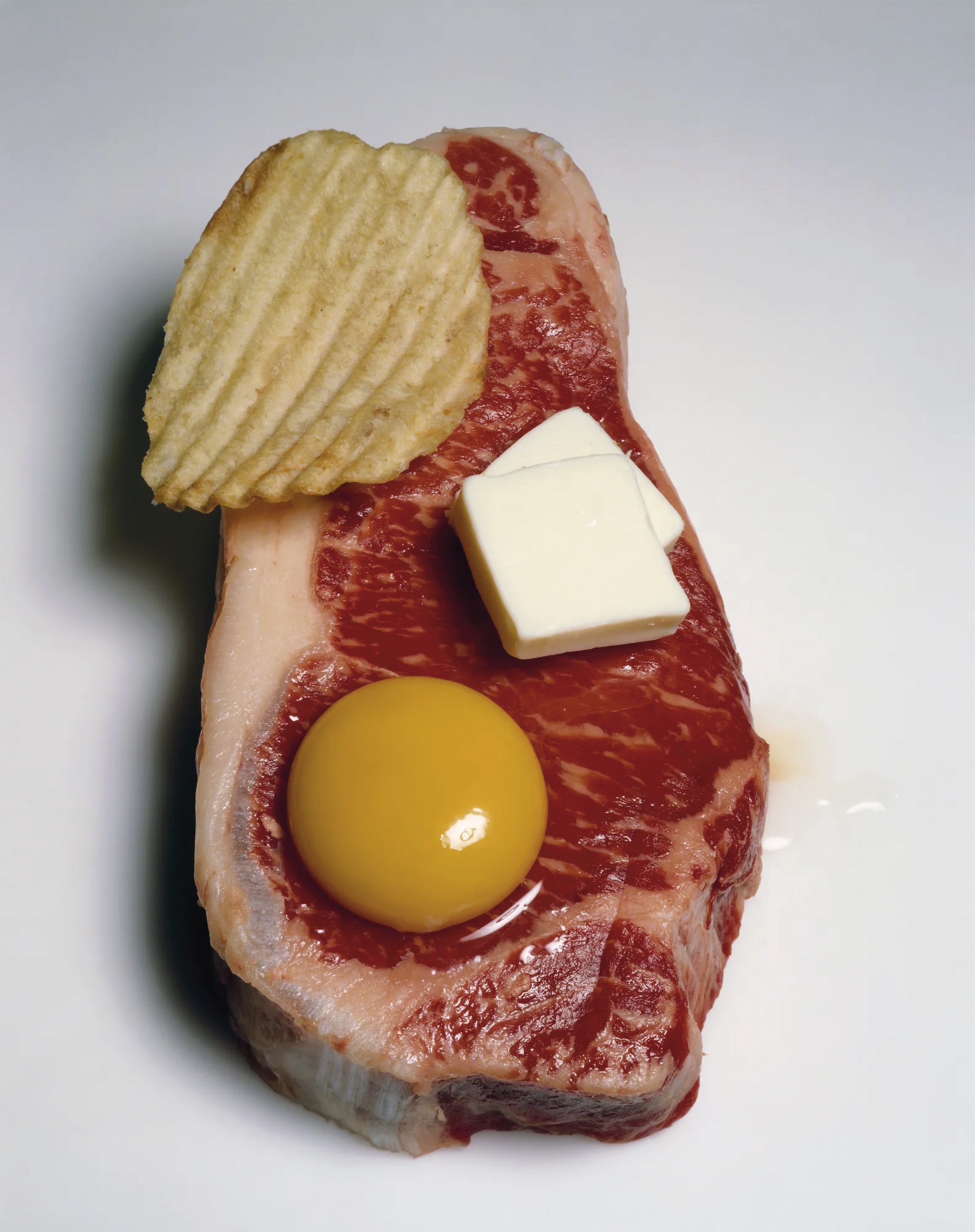

The only one to be saved is Margot, the beautiful young companion of Tyler (a haute cuisine sycophant who constantly makes use of stereotypical phrases such as ‘mouthfeel’ or ‘molecularity’), but only because she is a stranger to that environment as sophisticated as it is inconsistent. To do this, she uses a rather good stratagem: refusing the chef’s dishes, something no one else among his regular customers had ever dared to do, and asking him to make her a ‘real cheeseburger’ with a double patty, strictly American cheese, lots of onions and, of course, ‘fries’. Julian plays along: giving in to the girl’s request, he casts off his role of inspired chef, prepares the dish and, to top it all off, even packs it in a doggy bag for Margot to take away and eat elsewhere. A world turned truly upside-down: the quintessential fast-food product prepared in a fancy restaurant which literally engages in slaughter.

In a recent interview with El País, Rafael García Santos, the famous (and feared) Spanish food critic, who must have seen this film and well understood its message (which is slightly simplistic, to be fair), provocatively said that today the only restaurant where real culinary research is done is McDonald’s: ‘The best restaurant, the one that is creating the gastronomy of today, is McDonald’s.’ This statement, it must be made clear, was delivered after a very precise line of reasoning: ‘Every decade, a new chef takes on the mantle as leader of the world of haute cuisine. In the 1970s it was Michel Guérard, in the 1980s Joël Robuchon, in the 1990s Michel Bras, and in the 2000s Ferran Adrià, but since 2010 there has been no chef of historic importance.’ ‘Today’, Rafael García Santos continues, ‘chefs are rock stars, more interested in lifestyle and adoration.’ And so, he concludes: ‘The system is dead. That’s why Noma is closing. They don’t care about the customer, who they shamelessly take for a ride. Who is going to pay 500 euros to go to a restaurant?’ It’s hard to find fault with his logic: the recent news that Noma in Copenhagen, reign of the revered René Redzepi, is also about to close its doors confirms this.

As for his claim about McDonald’s, he offers the following arguments: ‘McDonald’s is targeting new generations of diners, connecting with new customers. And it is getting rid of waiters and cooks. It is using artificial intelligence, which is destined to flood the hospitality industry. That’s the future. Then these chefs will come along and say they invented it. The purpose of McDonald’s is to feed you. Although I wouldn’t say it’s gastronomy, it is the future.’

[...]

Share article