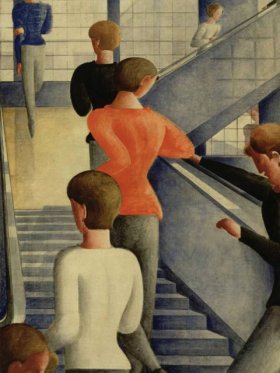

The unreleased photographs of this portfolio were captured in 2015 in London, where João Penalva settled in 1976 when he enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art, having ended an international career in dance with choreographers such as Gerhard Bohner, Pina Bausch, and Jean Pomares. Penalva has since established himself as one of the most celebrated contemporary visual artists, with a work that has gained notoriety for – among other things – the sheer impossibility of being summed up in simple formulas, as it juggles installation, image, text, voice, performance, dance and film. Exploring the diverse narrative possibilities of these mediums through the blurring of fact and fiction, Penalva has systematically explored the role of chance and the place of the viewer, the mechanisms of perception and the instability of interpretation, thereby building a palimpsest of memories, events and stories. The series reproduced in these pages displays an intricate web of arabesques, a jumble of scraps and cuts, featuring geometrical lines or accidental marks, in monochromatic tones that immediately bring to mind abstract painting. Yet, what is at stake here is a series of black-and-white digital photographs which João Penalva snapped during his daily walks between his home and his studio in southeast London, strolling, along with thousands of others, the busy streets connecting Marble Arch to Bermondsey.

This accretion of scratches and patches, spots and blots, leftovers and imprints on the surface of the city reveals a boundless morphological range, offering themselves up to the artist as genuine ready-made compositions. ‘I would say I had stumbled across paintings lying around the street pavements,’ stated João Penalva.2 These chance encounters with traces on the pavement conjure up the canvases of the Abstract Expressionists from the US, such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, which Penalva had once elected as his prime references when starting out as a painter – tying both names, and not by coincidence, to the choreographies of Merce Cunningham, by sharing in that common idea of the artistic process as a form of creative freedom and of being present in the world. This event of a spontaneous recognition of art on the pavements of London is reminiscent of John Cage’s epiphany in New York, in 1944, while he was waiting for the bus after visiting an exhibition, in which Mark Tobey showed his abstract paintings inspired by Asian calligraphy: ‘I happened to look at the pavement, and I noticed that the experience of looking at the pavement was the same as the experience of looking at the Tobey. Exactly the same. The aesthetic enjoyment was just as high.’3 Cage would always go back to that sudden illumination which elided the distinction between art and life, and later even sung this in poetic form: ‘Waiting for a bus, we’re present at a concert. Suddenly we stand on a work of art, the pavement.’4 Likewise informed by an attentiveness to everyday objects, in Penalva’s photographs this intimate relationship with painting has not only to do with the verticalisation of the image in space, but also seems to allude to the appearance of the initial reproductions of Abstract Expressionist canvases in the catalogues that first showcased them around the world. In another series, Penalva even printed a similar set of life-sized photographs on linen canvases prepared for oil painting, thus using the privileged medium of abstraction whilst emulating its language through the geometrical cracks, calligraphic spots, and mottled stains of chewing gum (also a motif in Gilbert & George’s work). The uncertainty between the mediums creates a transitive state in-between painting and photography, combining, on the one hand, a highly rigorous framing from the formal viewpoint, and on the other, the contingency of the actual image, which, like the pavements, is made up of flaws and accidents.

In João Penalva’s oeuvre, one could contrast the act of looking down at the ground with the act of looking up towards the sky from a previous work, Looking up in Osaka (2006), in which, wandering through the Japanese city, he started pointing the camera upwards. The resulting frames capture a dense weave of electric cables, poles, power lines and streetlights which, cut against the sky and depleted of any geographic pointers, draw masses, volumes and lines, in the guise of coloured silhouettes that are more akin to geometric abstractions. As with the pictures taken in the British capital, the act of looking down has brought out, inversely, not only microscopic attention to the pavement, but also a kind of expressionist surface of inscription, continuously redone by the movement of bodies and things, in a state of flux. Even though all of the images are meticulously geo-referenced in the title, bearing the postal code of the adjacent building, the space never amounts to an abstract area. It is rather an inhabited place that is made up of the sediments of passage. Originally conceived as an urban structure intended to be uniform and inconspicuous, the pavement appears here instead as a unique and unpredictable mosaic of debris, splinters, rifts, splashes and textures, which is to say, the mutant outcome of the practice of everyday life.

In some sense, this is a way of addressing the city, or a way of relating to place, which is common to experimental practices of photography within contemporary art – from Sophie Riestelhueber’s scarified landscapes, bearing the traumas once inflicted by history, to Rut Blees Luxemburg’s inventories of forensic traces within vacant places, to the peripatetic records of the art of walking with Francis Alÿs, or the erratic mapping of urban spaces with Gordon Matta-Clark. With Penalva, this harking back to the pictorial tradition does not evoke the structuring role of pavements in Renaissance painting, either fixating the illusion of depth or modulating the perspective. Instead, it mimics the idiosyncrasies of abstract composition and style, instilling asymmetry and disorder. The pavements are taken as a stage for meeting and discovering the body – the same routes were revisited later by the artist, and they no longer bore any of the traces or trails visible in all these pictures, reinforcing the idea of a screen in which, according to João Penalva, ‘everything, everyone leaves their mark’. As a space of inscription of the body and things, this metamorphosis of the urban space comes to resemble that of a literary text insofar as it lays us bare before the evidence that we are, as Manuel Gusmão put it, ‘singular historical bodies, run through by a tangled writing, a voice that is scripted, inscribed and exscribed – a tattoo and a palimpsest’.5 Michel de Certeau’s analogy between the language and the city is well-‑known: ‘The act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language’.6 However, João Penalva’s work throws into stark relief an additional dimension of this psychogeography, recently highlighted by Rebecca Solnit: ‘De Certeau’s metaphor suggests a frightening possibility: that if the city is a language spoken by walkers, then a postpedestrian city not only has fallen silent but risks becoming a dead language.’7 The idea of a tattoo and a palimpsest – at odds then with the revolutionary cry of May ‘68, ‘Beneath the pavement, the beach!’ –, gestures instead towards a rediscovery of daily life in its most banal constituent, in that dimension which Georges Perec has called ‘infra‑ordinary’,8 a form of attentive scanning of the cumulative and neglected surface of the city’s skin, which, by way of interrupting one’s familiarisation of everyday space, teleports us to another position from where something extraordinary can emerge. These images are, then, part of an experimental moment among the humanities and arts in terms of addressing spaces as intensive descriptions which do away with explanations, cultivating an intimacy with that which goes unnoticed, encouraging one to slow down and stop, cutting against the fast pace of these days. To a great extent, these approaches militate against the dominant ways of invoking a place during the first half of the twentieth century, caught between regional geography and local history, with its compulsive temptation to establish lines of contact between the territory and identity.9 In the wake of phenomenology, which made clear that human experience largely exceeds the scope of its attention, and which embraced the supposed indifference of things, a new sort of topological thinking came to reign supreme in philosophy – Walter Benjamin, for instance, became one of the first to start out from the issue of where, rather than the habitual what, how or why10 – and a critical tradition of the city as a choreography asserted itself, following Michel de Certeau, Jane Jacobs, and Henri Lefebvre. In the series of images by João Penalva, the cracks and faults in the asphalt and cement, the blemishes and drips, as tectonic plaques in permanent mutation, inscribe themselves within this important theoretical and aesthetic lineage. With an unmatched formal brio and elegance, they restore the prosaic surface of the everyday city through a slow-looking and imaginative appeal, transfiguring common things in singularly evocative and unforeseeable ways. As W. H. Auden once wrote, ‘the crack in the tea-cup opens / A lane to the land of the dead’.11

Share article