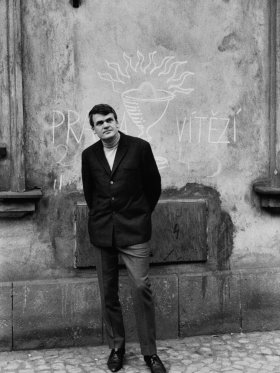

Claire Bishop is a British art historian and critic, professor of Art History at the City University of New York, and contributing editor of Artforum. She has authored several groundbreaking works such as Installation Art: A Critical History (2005); Participation (2006); and Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (2012). She has been working on two publications: a study about Merce Cunningham’s Events, and a collection of essays about attention and contemporary art since the 1990s, entitled Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance (2024). This book identifies a number of trends within contemporary art practice – research – based installations, performance exhibitions, interventions, and invocations of modernist architecture – and their challenges to traditional modes of attention. In this conversation with Electra, Claire Bishop has charted a critical path throughout the last three decades, pinpointing how spectatorship and visual literacy have been radically evolving under the pressures of digital technology.

The eminent British art historian and critic Claire Bishop, renowned as one of the leading theorists of the idea of participation in the visual arts and in performance, is about to launch a new book on the problem of attention in contemporary culture over the last thirty years. In conversation with Electra, this professor at City University of New York discusses exhibitions, installations, criticism and dance, exploring the radical ways in which digital technology has been transforming the idea of the spectator.

AFONSO DIAS RAMOS The constant focus in your work around the idea of participation in art has recently given way to the issue of audience attention. What has prompted this shift in focus?

CLAIRE BISHOP I wouldn’t say that participation has been a ‘constant focus’ of my work! It was a topic of my research 2004 to 2012. My first book was on installation art. I’ve also written about museums. What is a constant throughline in my research, going back to my dissertation, is spectatorship, the viewing subject. Secondary to this is an interest in historicising and theorising artistic strategies: installation, participation, and in the new book Disordered Attention three more: research-based art, performance exhibitions, and interventions. Why work on attention? One of the biggest changes in our culture and society over the last thirty years – a period that coincidentally coincides with what we call ‘contemporary art’ – has been digital technology. The speed and degree of change has been unimaginable; it affects how we communicate, how we think, how we research, how we write. Because it changes our experience of time, it also affects how we see. All this, I think, makes it a rich consideration for anyone dealing with art and spectatorship. In this book, I want to look at a thirty-year period of contemporary art historically, tracking changes over three decades, but through the lens of technological change. Any book on attention has to wrangle with two related discourses that have emerged since the 1990s. The first is the attention economy. None of us with a smartphone or computer is immune to its tentacles; every glance and click can be monetised. The other discourse is around ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). ADHD medication has become a central to maintaining performance in the university and neoliberal workplace; almost 10% of US schoolchildren are diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed medication. ADHD discourse brings together questions of pedagogy, literacy, neurobiology and neoliberalism, and pathologises distraction in ways that unexpectedly inform considerations of visual art and performance.

"One of the biggest changes in our culture and society over the last thirty years – a period that coincidentally coincides with what we call ‘contemporary art’ – has been digital technology."

Andrea Mantegna, Martirio e trasporto del corpo decapitato di san Cristoforo [The Martyrdom and Transport of the Decapitated Body of Saint Christopher], 1457 (detail) © Photo: Scala, Florence / Cameraphoto / Church of the Eremitani, Padua

ADR In what ways has the new attention economy born in the last years, competing for the consumer’s focus at all times, shaped how we attend to art and to performance?

CB My answer is: indirectly, i.e. not in the ways we would expect. Of course, there is Instagram art: highly colourful, photogenic installations that encourage a consumerist relation to experience – from the Van Gogh Experience to Yayoi Kusama installations to Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised, a massive, popular ever- ‑undulating AI video in the lobby at MoMA. But I’m more interested in the subliminal, complex and ambivalent ways in which an omnipresent, screen-based digital environment affects visual literacy and the construction of aesthetic experience. I approach the problem perversely, by not going to digital and/or post-Internet art. The force of an attention economy is actually best seen in artistic strategies that at first glance seem to have the least to do with technology: the use of archival materials in research-based installations, for example, or the presentation of live performance in museums and galleries. These strategies exhibit a push-and-pull relationship to the digital: on the one hand, the research- based installation seems to fetishise old technologies (postcards, ephemera, faxes, 35mm film, slide projectors…); on the other hand, its rhizomatic methods of presentation and sheer quantity of materials have internalised what David Joselit calls the ‘epistemology of search.’ Or take performance exhibitions. On the one hand, live performance in the gallery refutes the virtualisation of experience and offers the thrill of physical presence and proximity; on the other hand, such performances are seemingly irresistable in terms of photographic capture, seem to anticipate photographic circulation and are even structured around digital techniques (like looping and refreshing) in order to last the duration of museum opening hours.

ADR Your new book proposes four models of handling this new attention economy. Can you tell us a little about how you went about framing these issues?

CB My interest is in defining and exploring some artistic strategies and asking some uncomfortable questions about them. So to be honest, the modes of working came first, and only retrospectively did I come to realise that a unifying theme could be attention. Each one has been a complete struggle to write, as I was dealing with a vast quantity of examples that seemed continually to change. It took me a long time to realise that I had to be more historically minded in order to narrate what was going on. The first chapter is on research-based art and the viewers’ decreasing appetite for handing large quantities of information in an installation or exhibition. The second is on performance exhibitions and social media: rather than categorising people’s use of phones in performances as ‘distraction’ and thus a problem, I see cameraphones as a return to pre-modern sociability. The hybrid spectatorship that ensues is also an opportunity to critique modern (i.e. fully focussed) spectatorship as a relatively recent invention.

ADR In looking at literacy and spectatorship over the last two decades, you came up with two specific rubrics: skimming and sampling. What do these operations entail?

CB When faced with huge quantities of text (or other archival material) in an installation, there are basically three responses. You can skim – read diagonally to try and get the gist. Or you can sample: look at one vitrine/table/corner of the installation and assume it’s representative of the whole. Both are time-efficient ways of dealing with informational inundation. The third response is to diligently go through the entire installation and read every word – but this will always come at the cost of seeing the rest of the exhibition! I tend to do a lot of skimming in exhibitions. Not many works make me sacrifice the rest of a show to do justice to them.

[...]

Share article