In this essay, Rushdie starts out by reminding us that the three major novels of the 18th century, (one of the greatest eras of English literature) – Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy –, were a resounding success, although the name of their authors (Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne) did not appear either on the cover or on the front page. He comments:

With the title ‘Autobiography and the Novel’, published in Languages of Truth, the British writer of Indian origin Salman Rushdie wrote an essay in which intelligence and malice play off each other prompting an inquiry and raising questions that come close to the ones tackled in the ‘Subject’ section of this issue of Electra. The latter also highlights and echoes the confusion that envelops these questions today, swelling like a powerful vortex.

Charles Robert Leslie, Gulliver presented to the Queen of Brobdignag, 1835 (detail) © Photo: John Hammond / Scala, Florence / NTPL / Petworth House, West Sussex

Just two hundred and fifty years ago it was possible for books to become famous and celebrated, as all these books were in their day, and for the author to remain in the shadows. The personality and life story of the author was not deemed to be of any relevance to his work. […]. Fiction was fiction; life was life; two hundred and fifty years ago, people knew these were different things.

This is no longer the case. And if there is a writer we can blame for this, it is probably Charles Dickens. If Dickens did not wholly invent the cult of the writer as a public personality, he certainly did a great deal to popularise it.

The author of The Satanic Verses points out that Charles Dickens wanted to make it known, publicly and explicitly, that he had used his personal life, with all of its events and anecdotes, persons and situations, environments and places, as material and the driving force behind his novels. He states:

Writers, after Dickens, might not have become more willing to fictionalise their own stories, but readers have certainly begun to believe that they do. Nowadays, there is a prevalent assumption that all novels are really autobiographies in disguise.

Every contemporary novelist will tell you that the question he or she is most frequently asked is the autobiography question. ‘How autobiographical is it?’

Raphael, Little St. Michael, 1503 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Louvre, Paris

The author of Midnight’s Children then describes a recurring and symptomatic situation: even if the author adamantly denies the autobiographical origin of their fictional book, readers demand ‘autobiographical reality’ as the condition of truth and dignification of what they are reading. Without this, it is as if the book was not autenticated and they were being deceived by the author. Without this, it is as if they were being sold a lie. Without this, it is as if they cannot believe what they are reading. Without this, it is as if they cannot identify with what they are reading.

In this way, they apply themselves to snooping into the author’s life, unveiling their past and present, unearthing their sexual orientation and love life, trying to find some unknown fact, searching, probing, guessing, and confirming secrets, intrigues and rumours. Also, symmetrically, they are always ready to suspect, doubt, distrust, refute, reject, discredit.

To illustrate this form of madness, sometimes mild, other times wild, manifested today by many readers, which causes them to demand that all that they read be the real life of the author and of those who populate their existence, Rushdie relates that he and other writers are hounded by both male and female readers. Frenetic or furious, they display an unchecked burning desire to identify, know, touch the reality that, according to them, fiction must necessarily relate and depict in order to be true fiction.

With this goal, they conceive pretexts, motivations and intimate reasons, performing a mutual psychoanalysis of identification and correspondence between the author and their characters, even if the signs that might substantiate this position do not exist, are invented, unlikely or far-fetched. Those who demand that everything that they read be real, create the most despicable form of fiction for their own consumption – that which does not know or recognise itself, resembling factual lies.

According to Rushdie, this obsessive autobiographical and sub-realist insanity, for which fiction only exists if it ceases being fiction, goes to the point of many of the author’s unknown readers wanting to see themselves as characters of the books. Despite fervent refutations by the author, they continue to see themselves depicted in those pages, which they believe also belong to them. For them, these refutations amount to a perfidious game that the writer plays to aggrandise themselves or even avoid paying copyright fees, at least of a moral nature, to that valuable source of inspiration – the readers themselves…

Salman Rushdie does not deny the interest, curiosity and pleasure that learning about and snooping into the lives of the authors whom we read and love (or those we do not love) can provide. He confesses that once in a while he does the same in good conscience and with serene delight. But he alerts and forewarns us, so that this does not lead to nefarious misunderstandings and fatal mistakes, causing us to confuse fringes with centre, essential with accessory, substance with attribute, cause with consequence, unnecessary with indispensable, insignificant with significant.

Examining a few novels that give form and meaning to the history of modern and contemporary literature, Rushdie sheds light on the relationships between citizen and author, experience and writing, life and work, showing that they are complex and contradictory, indirect and oblique, diverted and refracted, reflected and selective, transcended or even falsified.

Referring to two major novels of the 20th century, In Search of Lost Time and Ulysses, and specifically to their authors and characters/protagonists, he comments:

It is plain that Stephen Dedalus is close to James Joyce and Marcel […] shares a great deal with his creator, Marcel Proust. And yet Stephen and Marcel are not flesh-and-blood creatures. They are made of words, and a life lived in language is quite other than a life spent breathing air. Stephen is not Joyce, though he went to the same school and shares his author’s modest desire to ‘forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race’; and Marcel is not Proust – for one thing, he is heterosexual, and for another, he seems a good deal less frightened of the world, and gets about a great deal more, than his author in his famous cork-lined room. Every literary version of the real – a real place, a real family, a real man or woman – is just that, a version, and it is dangerous to equate it with that slipperiest of ideas, ‘truth’.

And, as a kind of moral of the story, Rushdie concludes with melancholy satisfaction:

There are good reasons writers so often choose characters who are avatars, incarnations of themselves. It is useful to be able to speak, think and act through a shadow, an alternative ‘I’, to go down a road not taken, to make a variation on the theme of yourself.

This essay ends with Shakespeare, giving literary credence to Jorge Luis Borges. The lack of definite information regarding the personality and life of the poet of Sonnets and playwright of Hamlet allows, and even invites us, to imagine clues, hypotheses, suggestions, speculations, scenarios, simulations. Nonetheless:

The point about Shakespeare is that he can be endlessly speculated about in this way, but he can never be pinned down. And so the attention turns again, as it must and should, away from the life and back to the work.

Henry Wallis, The Room in Which Shakespeare Was Born, 1853 © Photo: Tate, London

When speaking about Rushdie and his essay ‘Autobiography and the Novel’ we cannot forget that he tragically experienced, in both flesh and spirit, the risks contained in the dangerous and abusive relationship that is at times illegitimately established between the life and the work.

After the publication of his book The Satanic Verses, everything changed for him, especially himself. And his place in the world and that of his books also changed. From his death sentence – the fatwa –, in 1989, to his stabbing in 2022, death, with its threat, presence and anguish, became the terrible thread that connects and binds Rushdie’s life and work. Every day, every hour, every minute, this thread is attached to him, whether he is walking down the street to go to the doctor, going out to lunch with a friend at a restaurant, or writing the words of his next novel in his office.

Author of the Work – Work of the Author – Life of the Author. This triangle, with the sides that show or conceal themselves connecting its vertices, making known or hiding the angles that constitute them, carries with it a millenary history. This history reveals what each era, civilisation, culture and society thought about those who created or represented, symbolised or transformed, ruled or destroyed it.

By ‘work’ here we mean a book, painting, sculpture, play, film, piece of music, philosophical system, church or religion, building, political regime, constitutional law, social reform, theory, technique, scientific discovery, company, business, recipe, drink, athletic accomplishment, object, artefact, tool, machine, search engine, social media, nuclear weapon, war, peace, revolution, victory, defeat…

By ‘author’ we mean those who imagined, invented, created, projected, erected, performed, activated, revoked, or brought down one of these works. They might be a writer, philosopher, theologian, scientist, artist, architect, designer, engineer, economist, manager, politician, statesman, jurist, chef, tailor, sportsman, jeweller, carpenter… And this list includes all genders.

When we say this we do not mean that everything is interchangeable, or that works such as these have the same value: Fra Angelico’s The Annunciation, the tailleur Chanel, Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, Starck’s citrus juicer, Álvaro de Campos/ Fernando Pessoa’s Naval Ode, Judson’s zipper, Matisse’s Dance, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, Charlotte Perriand’s chaise longue, the abolition of slavery, the contraceptive pill, beef Wellington, Coca-Cola and Facebook.

But what differentiates and ontologically separates these things on the multiple levels that should be considered does not affect the key question that has intensified in our time. In a nutshell, the relationship between the work, the author and the life, implied in various dimensions and meanings.

This relationship entails anthropological, moral, artistic, political, psychological, cognitive, sociological, and technological values. What words can be used, or have been used, to give an account of this link and the laws that govern it? Interdependence, autonomy, independence, subordination, hostility, correspondence, coincidence, juxtaposition, distinction, conflict?

Throughout the many centuries and eras that these words have been used or passed on to the future, the authors have been many things in their own eyes and in the eyes of others. Their work has accompanied them in these variations of their condition and even interruptions to their status. And the link between the work and the life has also appeared stronger or weaker, more present or more absent, more innocent or more dangerous, more lucid or more blind.

There have been times when, heroic and exemplary, busts of themselves, only the authors existed, their works avatars confirming and glorifying them. In more recent years, the authors disappeared and their deaths were declared as the death of God had been declared (Georges Bataille spoke of the ‘death of the author by the work’). There have been times when to know the work well we had to know the life well (Sainte-Beuve and João Gaspar Simões, in their biographies of Eça de Queirós and Fernando Pessoa). There have been times when knowing the life (people said) did not help us to know the work. In the middle, there were those who defended that it was not the life that helped us to understand the work, but the work that made a decisive contribution to explaining the life (Susan Sontag on Walter Benjamin). Since Classical Antiquity we have talked about life as a work of art (it was a topic that interested Michel Foucault immensely at the end of his life, one of the authors, with Barthes and Blanchot, of the ‘death of the author’). Master of all paradoxes and illusionist of all contradictions, Fernando Pessoa had Bernardo Soares, in The Book of Disquiet, indifferently narrate ‘my autobiography without events, my story without a life’.

There have been periods when biographies, acclaimed as a literary genre, proliferated and others when they were scarce and culturally discredited (the philosopher Emil Cioran noted: ‘Incredible that the prospect of having a biographer has made no one renounce having a life.’)

A tireless and continuous writer of biographies, Stefan Zweig was one of the most read and translated authors of his time and of the times that followed his time. Later and for a few decades, his books almost disappeared from bookstores. He was considered a dated writer who only pleased a few people. Now his biographies have invaded shop windows, display cases and bookshelves, enjoying a revival and global rediscovery. Moreover, there has been a rehabilitation of biography and autobiography as omnipresent genres. What does this mean and signify? The dossier of Electra 22 tries to answer this question, as well as others prompted by it, often asking even more questions.

The issue of the link between the life and the work is intricately connected to the issue of the relationship between public and private, the boundary between which has disappeared and whose hierarchy, in our time, has gradually transformed, shifted and inverted itself.

Nowadays, there is, in every domain, a widespread and amalgamating confusion between the ‘social I’ and the ‘authorial I’, a lack of distinction firmly, belligerently opposed by Marcel Proust. He tried to argue his position in his essay ‘Against Sainte-Beuve’, stating that a work of art is the ‘product of a different “I” from that which expresses itself in our habits, in society, in our vices’. He concludes: ‘The man who makes verses and who chats in a salon is not the same person.’

Turning this founding position (of genetic criticism, we would say today) into a mark of rupture with Sainte-Beuve, the most acclaimed French literary critic of his time, Marcel Proust did not stop reiterating, on this subject, his declarative radicalism:

All this bears out what I was saying to you, that the man who lives in the same body with any great genius has little connection with him, but he it is whom his intimates know, so it is absurd to judge the poet by the man, as Sainte-Beuve does, or by the hearsay of his friends. As for the man himself, he is only a man and may be utterly ignorant of what the poet who dwells in him wants. And maybe it is better this way.

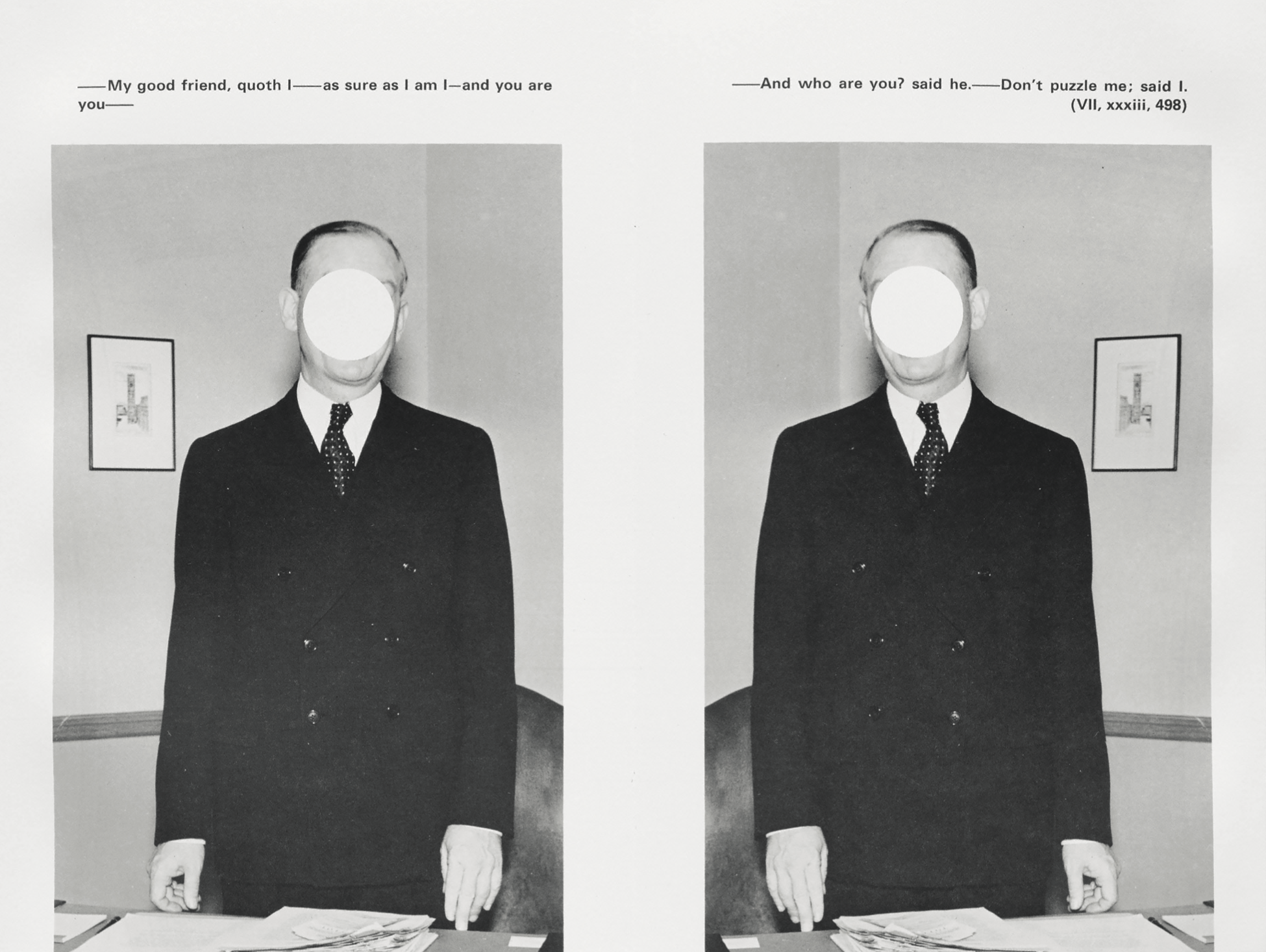

John Baldessari, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, 1988 © Photo: Scala, Florence / The Museum of Modern Art, New York

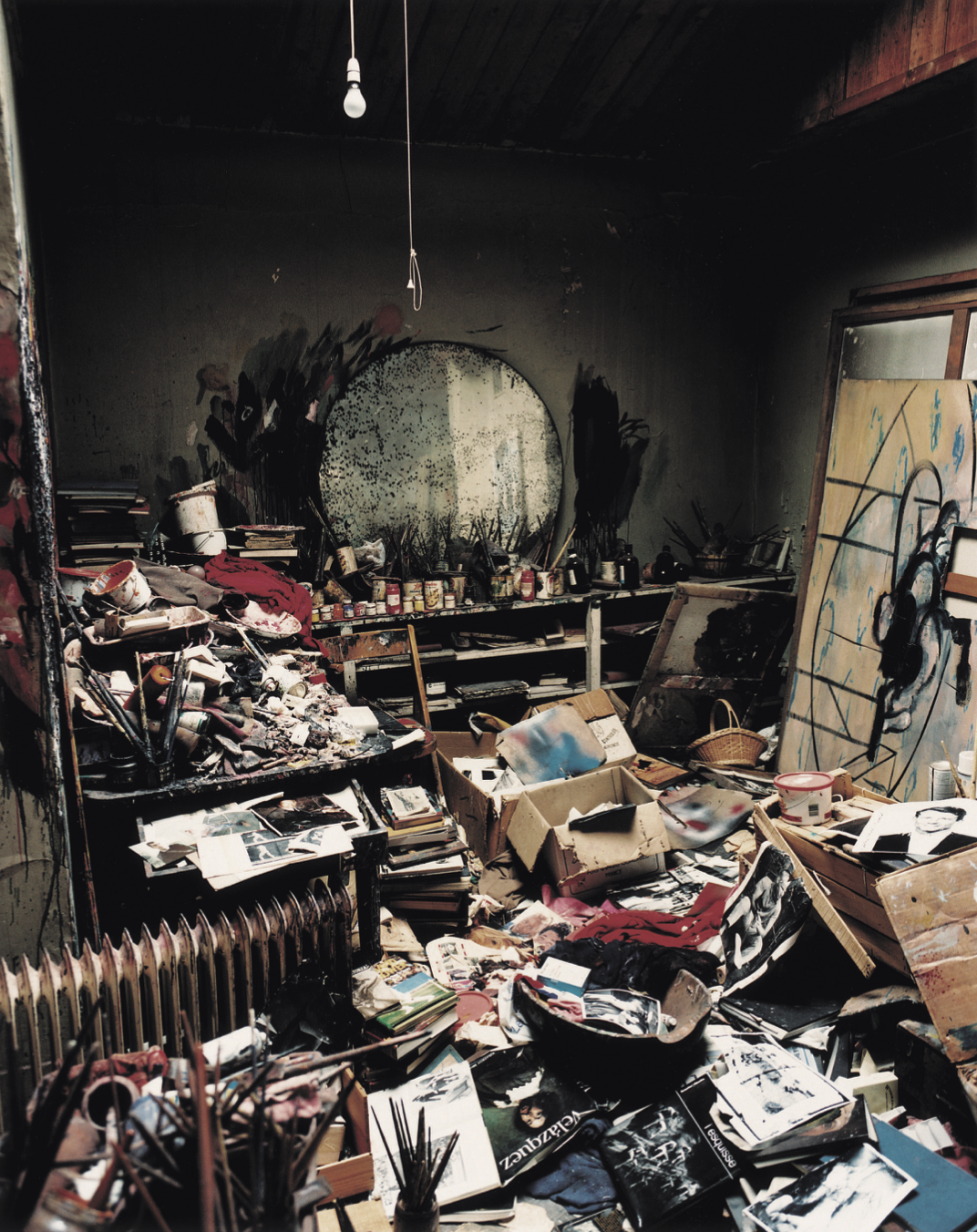

Rudolf Nureyev’s apartment in Paris, 1985 © Derry Moore

Proust had many followers who took his theory to the extreme. Nonetheless, his work has such a strong connection to the people and things of his life – and everything that happened in it – that knowledge of his biography provides a vital and enlightening contribution to understanding his work. Furthermore, the work helps us understand a life, which in his case only came into full fruition in the work and through the work.

According to many, given the excessive attention, whether aggressive or complacent, focused on life today – biographism and autobiographism –, our time is suffering a regression, although it is convinced that it is achieving progress. This regression is part of a more general moral, political and cultural regression, which ceaselessly manifests itself in almost every domain of individual and collective life.

For instance, some mention Pablo Picasso’s treatment of women as a reason to disqualify his work, or even cancel him and his work. Those who think this way exhibit a confusing and dogmatic moralism that makes them incapable of distinguishing between the life and the work. They cannot assess either one with criteria that are necessarily different and mutually clarifying.

This is why in this dossier we also reflect on the relationship between the morality of the life and the morality of the work. In order to claim that ‘Madame Bovary is me’ Gustave Flaubert did not have to go to the civil registry office to change his gender and name, or to a clinic to change his body and sex. He only had to write a novel with the title Madame Bovary…

In a beautiful evocation of the masterful author of The Portrait of a Lady, published in the ‘Register’ section of this issue of Electra, the renowned author Colm Tóibín talks about the relationship between the life and the work of the great American-British novelist, who once said that ‘art makes life’:

James was the most tactful of artists, keeping himself and his views out of sight, being ready to disappear for the sake of his art. He did not have a dramatic life or profound opinions on matters of the day. He had a polite, playful, distant, steely temperament. He was fascinated by money and by class, and by secrecy and treachery. His own secret – his homosexuality – was well kept by the very few who knew or suspected. His dislike of Oscar Wilde arose not only from Wilde’s success as a playwright in the years when James’s own plays failed, but Wilde’s flaunting of his sexuality and, indeed of his Irishness.

In these dramatic decades of the 21st century, James’s attitude would be viewed as strange, arousing concern and even contempt. In these hectic and compulsive days, we all want to be ruthless judges of everyone else. Therefore, misunderstandings proliferate, mistakes increase and masks abound. The same is true of unacceptable abuses, caricature-like intolerances, irredeemable injustices and sacrificial penitence.

There are those who give the name of identity affirmation to the narrowest and most aggressive puritanism supposedly turned inside out. There are those who designate the most backward obscurantism as civilisational progress. There are those who call the most threatening despotism an act of liberation. There are those who use the name of diversity for the most intolerable homogenisation and the most threatening unanimism. There are those who denominate the most invasive massification as self-determination. There are those who proclaim freedom of speech in order to use it as an instrument of censorship, manipulation and lies.

This is why, if we think critically about the Author-Work-Life triangle (which frequently becomes a quadrilateral with another vertex consisting of the Reader), we will better understand the geometry of forces that make our time move.

There are plenty of questions we may ask. For instance: is the current wave of autobiographism in its many forms, including the one which in literature is called ‘autofiction’, not an extension or projection of the murky sea of narcissism that invades and pollutes every land and of which social media offers a terrifying view at every moment? Is this wave not another sign of the elimination of the insurmountable boundary that existed between the private space and the public domain, which took centuries to define, affirm and defend? But we know there are those who answer these questions by saying that the arrival of a new transparency, putting an end to the old opacity generated by a morality of hypocrisy, transgression, concealment and impunity, constitutes an unprecedented ethical progress and civilisational advancement.

In Getting Lost, the diary that Annie Ernaux wrote and recently published to give account of an intense and secret love affair that lasted for one and a half years, she stated: ‘Yesterday, it came to me with certainty that I write my love stories and live my books, in a perpetual round dance.’

Before that she had said: ‘During this period, the only place where I truly wrote was in the journal I had kept, on and off, since adolescence. It was a way of enduring the wait until we saw each other again, of heightening the pleasure by recording the words and acts of passion. Most of all, it was a way to save life, save from nothingness the thing that most resembles it.’ This is how she ends this journal that she wrote with the intention of publishing it: ‘There is this need I have to write something that puts me in danger, like a cellar door that opens and must be entered, come what may.’

In The Story of My Life, from the 18th century, Giacomo Casanova writes: ‘My life is my matter, my matter is my life.’ And his biographer Philippe Sollers comments: ‘Usually novels serve to imagine the life one did not have, here it’s the opposite: here is someone who realizes, like a last judgment, that his life has been woven like a book, an immense novel.’

This is confirmed by Casanova who says: ‘In remembering the pleasures I have had, I renew them, I enjoy them a second time, and I laugh about the suffering I have endured and that I no longer feel. Member of the universe, I speak to the air, and I see myself as giving an account of my management the way a butler does to his master before disappearing.’

With over two hundred years between them, Casanova and Ernaux say the same thing, and yet do not say the same thing.

They say the same thing, since writing gives them both the opportunity to relive life – and also correct, erase and add to it.

They do not say the same thing, since the two eras and worlds where their writing takes place and their lives are lived are very different and because between these two eras and worlds so many things and so many changes have occurred that even what seems the same is, in fact, different.

Whatever the case may be, Giacomo and Annie could easily talk to each other about the exhausting and inexhaustible topic of the relationship between the life and the work. And the two could also talk to Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne about the advantages and drawbacks of placing the author’s name or not on the cover of the book they wrote.

All of these voices, with what they state and deny, ask and answer, show and hide, populate this dossier of Electra, whose subject is, due to its nature and scope, genealogy and history, one of the most infinite and labyrinthine, osmotic and undefinable of all that we have tackled.

When we read the texts that compose the ‘Subject’ section of Electra 22, we know that they address some of the questions that can give our time a clearer biography of itself, thanks to the similarities and differences that they have displayed throughout the centuries.

On the vital importance of these questions and what they bring up in terms of depth and breadth, perhaps a general melancholy meditation, with the verified certification of the great anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, might be more eloquent and enlightening than other more direct or obvious considerations regarding these topics:

Were some ten or twenty centuries of history to be suppressed at random, our understanding of human nature would not be appreciably affected. For men and women differ, and even exist, only through their works. They alone bear evidence that, among human beings, something actually happened during the course of time.

Francis Bacon’s 7 Reece Mews studio photographed by Perry Ogden in 1998 © Perry Ogden

Share article