2021: the year of Dante. He died in Ravenna seven hundred years ago, longing for an official recognition that never came, and refusing to bow to short-lived attempts at conciliation from the city that had accused him of, among other things, corruption during his transient poetic career. Dante Alighieri, the son and brother of moneylenders, would probably have appreciated the commemorative celebrations in his honour that have kept cropping up over the last one hundred and fifty years. He would undoubtedly have had something to say about their content. His greatest obsession – apart from his fixation with Beatrice, a young woman from the upper echelons of Florentine society, who died at an early age – was to manage and control what was said about him and about his writing. Early on, this urge for control made him an innovator, but unsettled his contemporaries. In 1283, in Florence as elsewhere in Italy, poems had been written for some time in a language other than Latin (slightly less than prose: mostly translations, and not of the finest quality). This ‘globish’, the preserve of the universities, brought together students and teachers in a very elitist ‘intellectual internationalism’. The ‘Florentine’ variant of this other language was not yet considered the most stylish: Dante’s generation, and in particular his good friend Cavalcanti, played a part in giving it more distinction in the cultural field, as Pierre Bordieu would say. This poetry was, for the most part, a poetry of correspondence. It emerged from communication ‘by letter’, one of the ways in which those privileged enough to be able to write exchanged views – but above all took stock of each other, displaying their own status.

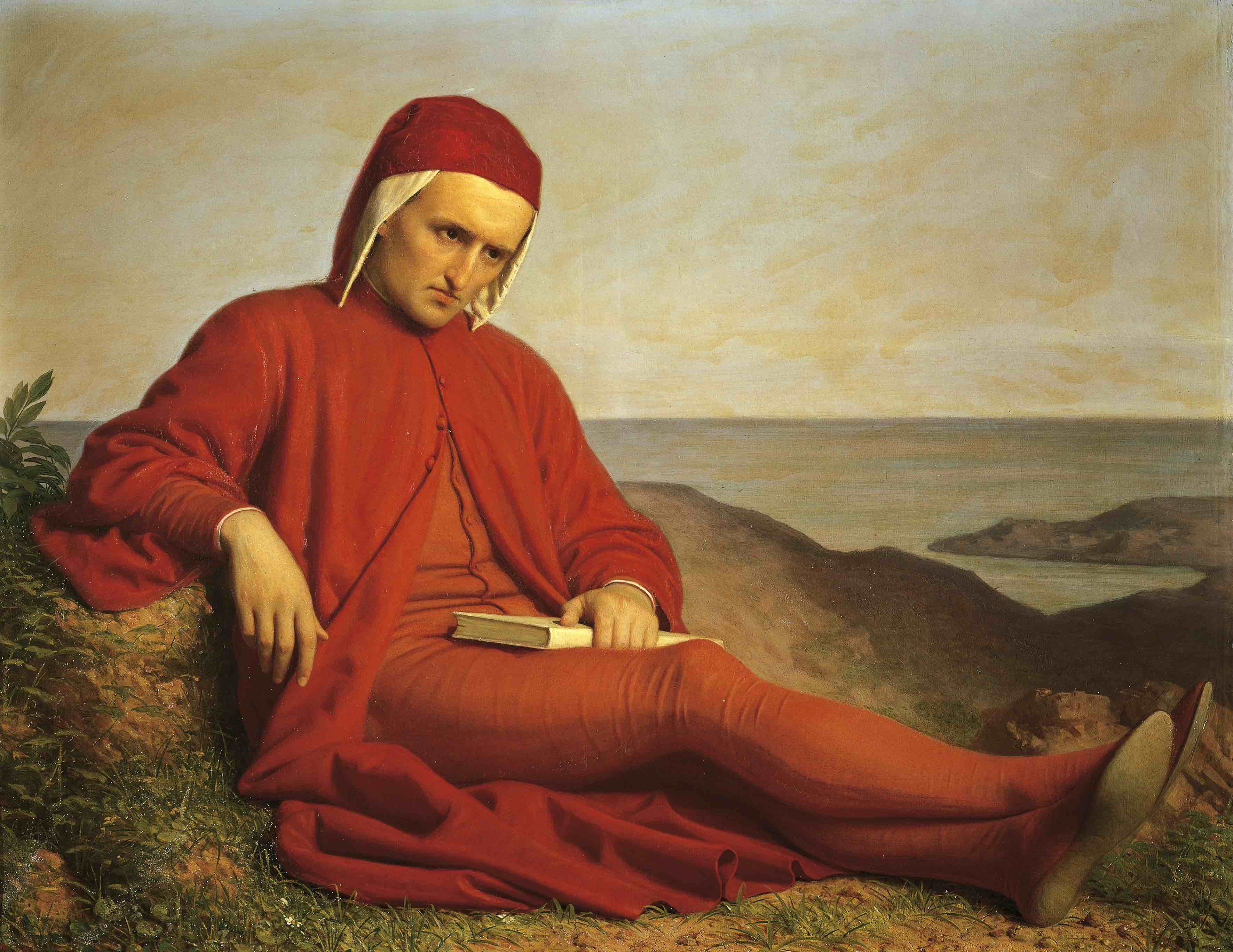

On the seventh centenary of Dante’s death (1265-1321), Antonio Montefusco, professor in Medieval Latin Literature at the Universidade Ca’ Foscari de Veneza, discusses the poet of the Divine Comedy, who ‘invented the figure of the modern intellectual’ and introduced the ‘vernacular’ to poetry in the place of Latin. He looks critically at the ideological and political uses to which official commemorations of earlier centenaries have been subjected since the 19th century.

Domenico Petarlini, Dante Alighieri in exile, 1860 © Photo: Scala, Florence / DeAgostini Picture Library

"His greatest obsession – apart from his fixation with Beatrice, a young woman from the upper echelons of Florentine society, who died at an early age – was to manage and control what was said about him and about his writing."

Sandro Botticelli, The Divine Comedy (studies), ca. 1480 (detail)

These poem-letters, verses written to other recipients, served to redefine the boundaries of intellectual work in the vernacular. It was the ‘enclosure’ of this new field of knowledge that made it attractive, prompting a battle for hegemony with the academic world. Additionally, there was the fact that the task went completely unrewarded: teachers were paid by their students and from prebends; poets usually did other work – or, like Guido Cavalcanti, they were cavalieri: that is to say aristocrats. During the decade from 1283 to 1293, when everything changed in the history of Italian vernacular literature, Dante quickly showed himself to be not only skilled at producing poems about love and open to the most recent developments in philosophy (almost as much as Cavalcanti), but also to be extremely litigious. He did not accept the reactions to his poems, feeling that they almost always trivialised his work. It was partly for this reason that he began to organise his writing into structured cycles; then he added his own commentary. In the Vita Nova, a work in prose and poetry published towards the end of this extraordinary period, this commentary resolved itself into a love story between the protagonist and Beatrice: a love that was impacted by Beatrice’s death, but did not end with it. Other poets until that time had tormented themselves with the impossibility of true love: they sought the prize of a physical coupling that never materialised, even taking the view that the suffering caused by the failure of that objective could produce a pure mental state of bliss. This was not so with Dante: he is not the one who is verging on death; it is Beatrice who departs this life. He would remain faithful to this love, and the Vita Nova ends with the promise of an even greater work, something more beautiful, something visionary, but on the same theme.

This framework remained a constant with Dante throughout his life. It was not easy to persuade his peers of this ultimately incomplete love story; but there was more to it than that. After Florence had banished him and sentenced him to death, his unfinished work Convivio would exhibit the same narcissistic compulsion. Its structure consists of his own commentary on fifteen canzoni: a self-centred encyclopedia in which his poetry, explained using the most polished tools of university learning, would allow even the illiterate to access the highest levels of knowledge. In parallel, another incomplete text – the De Vulgari Eloquentia – seeks, in Latin, to convince intellectuals of the primacy of vernacular poetry. And what about the monumental construction site that is the Divine Comedy? Here we have a colossal textual device in which the whole of the afterlife is invented, designed and described in the minutest detail, the story of a quest that plunges his first-person protagonist into another world. His earlier literary endeavours pale in comparison, resembling primary school exercises. And within this device, written and completed and revised (thousands of verses with hardly a single mistake, misconception, or contradiction: the sign of a compulsive perfectionist), the protagonist finds an almost Proustian space to portray himself, in essence, as a man tormented by the disappointment of being misunderstood.

"After Florence had banished him and sentenced him to death, his unfinished work Convivio would exhibit the same narcissistic compulsion."

Is this not a paradox? Here is a writer so convinced that he is conceiving and creating great things in a language so inadequate it is not able to express such an astonishing edifices, that he thinks and keeps repeating that you, dear reader, must continually sharpen your wits in order to understand at least in part what it is that this imagined world represents: a writer who at only twenty years old saw himself as a creator of ‘classic’ works, a man with the ability to overcome and defeat time.

[...]

Share article