Electricity arrived in Portugal’s capital in that dawn of the 20th century. The Tejo Power Station stood down by the river where boats plied back and forth carrying the coal that it devoured. The plant was the main generator of electricity for the city and the Greater Lisbon region for half a century. Continuous flows of workers laboured there, where soot was their life’s breath and their doom. Technology was changing work and everything else changed with it. It changed life and death. It changed physics and metaphysics. It changed society and poetry, as we can see in Pessoa. It changed economics and art.

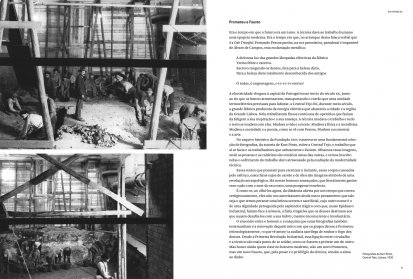

The EDP Foundation is home to a collection of photographs by Kurt Pinto. They bear witness to the Tejo Power Station, the work done there and the workers who toiled inside. We look at these pictures, where the people and boilers reflect each other, and we see on their faces the suffering of hard labour entwined with the exaltation of modern technology.

Those faces that posed for posterity, those bodies exhausted by their toil, those overalls soiled with coal and oil are symbolic images of an anthropological revolution. The faces of these threatened men, who literally earned their living with the sweat of their brows, portray a pungent innocence.

It is as if, looking at them now from a distance opened up by swiftly passing time, we do not have their permission to think otherwise than the fact that we are looking at secret and sacrificial beauty. The other name for this beauty is dignity pursued by the tragic splendour with which, in that industrial Epidaurus, they faced their nemesis, the vengeful fury that the gods reserve for those who dare to challenge them with their hubris, even if it is unconscious and involuntary.

The meeting between man and machine in these photos is the renewal of that myth in which the Greeks credited Prometheus (etymologically ‘forethought’) with the sacrilegious audacity of stealing fire from the gods. This connection between labour and technology has been made since the first Industrial Revolution, as one was a prosthesis of the other. But there were people who regarded modern man not as a new Prometheus, but rather as a new Faust, who sold his soul to the Devil in return for the privilege and possession of technology.

Opposites often attract and are confirmed in what does not destroy them. In the 1930s, Ernst Jünger published The Worker: Dominion and Form and Walter Benjamin released three versions of The Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproducibility. These two men viewed the world from such different places and through such different eyes. They acutely regarded their time and what was happening in it from a new perspective and compared it with the pasts that made up the past. They demonstrated unexpected and astonished agreement on one fundamental issue of their present that has grown vastly in ours: the overwhelming, imperative and operational rule of technology – and its central role in the configuration of humanity, existential functions, social roles and everyday behaviour.

In the opinion of the right-wing writer and the left-wing thinker, revolutionaries from two radically opposed revolutions who, one and the other, became the symbols and faces of two overbearing and hostile cultures, technology was by no means neutral, instrumental or merely utilitarian.

With the unsettling figure of Heidegger passing between them, they knew that technology was ontologically the founder of another being and another entity, of another art and another culture, of another space and another time, of another form and another world. Technology exerts its worldwide power as it levels, homogenises, standardises, massifies, secularises, denatures, deculturalises, resanctifies, refounds and reconstitutes. With its omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent sovereignty, technology changes humankind’s relationship with nature, with other humans and with itself. It changes the past, present and future. Technology makes reality unreal and unreality real.

Technology speaks a new language that everyone has learned to speak. Technology faces and overcomes the obstacles that spring up before it and pulls all vestiges along in its aura. For the two German authors, technology changed the image of the worker, and work would never be the same again. In his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, Karl Marx predicted: ‘Since the worker has sunk to the level of a machine, he can be confronted by the machine as a competitor.’

The worker becomes the subject and the object of technology, its producer and its product. Its master and its slave, its hero and its martyr. Its victim and its apostle, its spy and its detective. Its patient and its physician, its militant and its dissident. Its pontiff and its believer. Work is the altar and the worker the altar boy. It is in work that work becomes his body.

For 150 years, this debate has been made up of persistent, peremptory debates. In Tecnologia, Modernidade e Política, Hermínio Martins upholds that sociological literature on the subject in the 19th and 20th centuries can be recognised and distinguished by its membership of two ideal-type traditional families: that of Prometheus and that of Faust. The great Portuguese sociologist explained:

Share article