‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’

The brief history of the concept of sustainable development is well known. It gained its ‘right to the city’ with the definition quoted above. It was used in the famous 1987 Brundtland Report for the United Nations about the environment and development. Sustainable development made a timid appearance in the 1980 World Conservation Strategy prepared by the IUCN, the largest and most respected biodiversity and nature conservation organisation in the world. Its roots go back much further, however, demonstrating the so-far irreconcilable tension between its two concepts: the dynamic of growth and intensification associated with ‘development’ stands in contrast to the idea of balance and durability associated with the adjective ‘sustainable’.

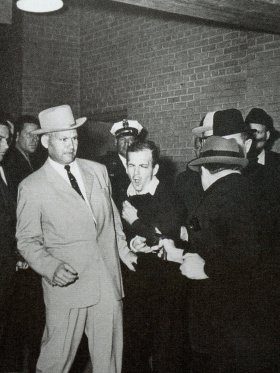

With the new media and social networks, the media landscape today has changed out of all recognition: the ground rules of the public domain have shifted completely, the old hierarchies have been overthrown, power has fragmented, whilst reality and unreality, not to say truth and untruth, are now interchangeable. Early hopes for a more transparent society have vanished and, instead, the world has become opaque. As things now stand, the press can no longer claim to be the Fourth Estate and what little power that still clings to it is fragile. The articles in this section set out to explore and understand where these and other issues may be taking us.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has moved into a phase marked by the law that defines Israel as the “nation state of the Jewish people”, adopting Hebrew as its only official language. Donatella Di Cesare, an Italian philosopher, and Éric Marty, a leading French voice in literary studies, have both written and taken a public stance on Israel, Judaism and the Jewish question. Here they comment on the law, taking different paths as to its meaning, reach and consequences.

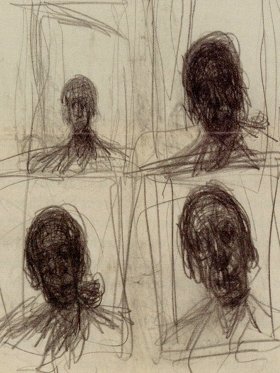

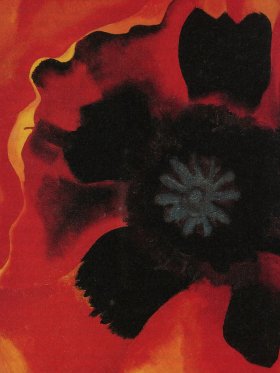

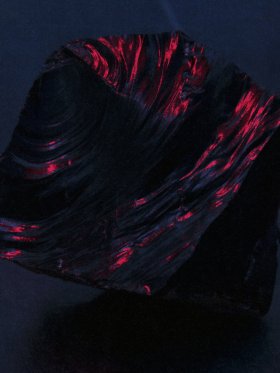

At the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Paris, curated by Helena de Freitas, a new exhibition places the work of Rui Chafes and Alberto Giacometti side by side and head to head. The magnetic force of attraction between the two bodies of work is clear to the viewer, in what brings them together and what keeps them apart. Nicolao Federico, writer, philosopher and curator, is familiar with the work of both Giacometti and Chafes and writes about the artists and the exhibition in which they come together.

On the other hand, after visiting Rui Chafe's exhibition in Paris, the poet, Manuel de Freitas, wrote the artist a letter. The starting point for the letter is a quotation from Alberto Giacometti that speaks of the imperfection, the virulence and the violence of poetry, painting, and sculpture. The poet talks to us about the darkness, the silence, the abyss and the night that are so palpable in this exhibition. And, as always happens with Manuel de Freitas, he talks to us about death.

Young ideals were one of the driving forces behind the social, cultural and political history of the 20th century. These days, there is no longer a place for the ideals that were once a young people’s prerogative. What has triumphed today is youth as an ideal and aspiration, i.e. young style and its culture. This desire, which has ceased to belong to an age-group, and the difficulties of access to full adulthood have rendered the borders between generational categories more fluid and opened up an injustice between generations. Many of the privileges that adults enjoyed no longer exist for the younger generation. The very large share that the idea of youth holds in the social and aesthetic market does not correspond to young people’s actual situation. In some ways, they are a robbed generation and, on the other, only they are fit to keep up with the times, which have been accelerating at breakneck speed. This dossier covers these issues.

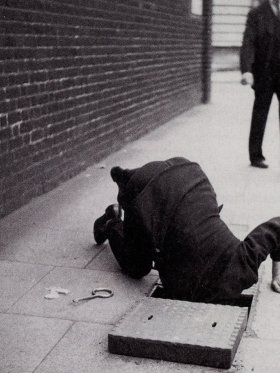

The writer recounts the experience of youth in a place that, in his view, is ‘Lisbon’s last suburb’. It is told in the first person and filtered through eyes that have meanwhile acquired the language and analytical tools needed to understand the hatred and cruel laws of a world – ours – full of borders and demarcated territories. It is of paradigmatic value here.

This testimony of a young high-school teacher on the outskirts of Paris speaks of a highly optimistic relationship with students that have been labelled problematic. Going against the most persistent stereotypes, she reveals how, unexpectedly, the students believe in the Republican values on which French schools are founded.

Pasolini had a difficult theoretical and political intellectual relationship with the students that were involved in riots and uprisings in 1968. Here, Vinícius Nicastro Honesko, a lecturer at Universidade Federal do Paraná and author of Pier Paolo Pasolini: Estudos Sobre a Figura do Intelectual, writes about the effects on Pasolini’s thinking of the idea behind his redefinition of a student. This idea was that young people were now denied the opportunity of a ‘revolutionary experience’.

On the basis of two films, the teacher, who is also (or especially) a poet and renowned translator, reflects on his experience of dealing with school-age youngsters. He takes the stage in a clear-sighted relationship with the ‘restless’ characters of students going through the different stages of a sinuous ‘mental path’.

‘Adolescence’ is a psycho-sociological category that appeared in the early 20th century and provided America and Europe with projections of wellbeing, education and progress. As a result, young people gained an important status. They became the subject of a new culture whose history is recounted in this article by Jon Savage, a British journalist and music critic. He is also the author of Teenage: The Prehistory of Youth Culture: 1875–1945 and Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture, as well as other books about pop and punk-rock music and culture, including a history of the Sex Pistols.

The modern obsession with the stages of life has not only produced ‘youth’, with its representations and its myths, but also old age. This article deals with a movie of life, very much to the taste of totalitarianisms, writes José Bragança de Miranda, with a critical eye trained to decipher the hieroglyphs of the present and its manifestations.

The Italian philosopher Remo Bodei is currently a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of a vast oeuvre, which includes a book entitled Generazioni (2014). In it, he points out that our history has been marked by a generational fracture. He insists that, as a result, we must accept responsibility with regard to the younger generation, on various levels, at a time fraught with uncertainties about the future.

Five young people from different backgrounds with different experiences in work and as students talk about themselves and the world on the basis of their own observations. They describe atmospheres and environments and show us some of the affective shades of our age. They also ask to be heard freely and attentively.

Youth as a sociological category is a 20th-century invention. Its political significance has been extremely important at certain times (e.g. May 68). Now that this political significance has gone, what is the social and political significance of youth today? The answer in this opening article is that youth has been absorbed by the bio-political mechanisms that govern their bodies and their performance.

The focus on animals (and animality), as well as the idea that humans have duties towards them and that it is intolerable to treat them as ‘things’ and deny them the faculty of feeling and suffering, has become one of the great issues of our time. It is present not only in civic movements that are highly active in the public sphere, but also in the social and human sciences, where an important field dealing with animals has emerged. Ethics, politics, sociology, anthropology, philosophy: today these disciplines are mobilised in an extensive operation that rescues animals from the silence to which philosophical thought – but not literature or art – has condemned them. The articles presented here deal with this type of reflection, in an interdisciplinary approach.

Palaeoanthropology and ethology, two disciplines to which António Bracinha Vieira has devoted part of his work as a professor and researcher, provide important scientific matter with which to reflect on what unites us with and separates us from the other living beings that share the biosphere with us – as anthropocentrism and its dreams of omnipotence carry on as usual.

The territorial behaviours of birds and the political and creative analogies that they generate are the main focus of Vinciane Despret’s research. The Belgian philosopher of science, an important figure in Animal Studies, has discovered the importance of ethology in the course of her career.

The work of the Italian sociologist Alessandro Dal Lago includes a contentious book entitled Genocidi animali (2018). Written with two friends, Massimo Filippi and Antonio Volpe, the slim volume caused controversy for using the word ‘genocide’. This article, beginning with a biographical narrative, looks at the “history of philosophers’ indifference towards the animal world”.

Massimo Filippi, a professor of neurology in Milan, is a distinguished anti-speciesism scholar (see, among other work, Questioni di specie, 2017) and a relentless critic of the strict separation of humans and animals, which, according to him, produces and legitimises the ‘crimes’ perpetrated against animals. His article can be read and compared with the one that follows it, by Vasco M. Barreto.

Vasco M. Barreto, a scientist and researcher at the Faculty of Medical Sciences, Universidade Nova, Lisbon, discusses ‘speciesism’, a key concept for the animal rights movements. He demonstrates that it is based on fallacies, contradictions and lacunae, of which the work of the controversial Australian philosopher Peter Singer, author of Animal Liberation, is an example.

Never before has there been such a lot of public discussion about animals, so much care and concern about how they are treated and what happens to them. Never before have animals, and not just pets, played such an important role in the human and social worlds. Today there is a very far-reaching, lively ‘animal question’ that is simultaneously galvanising philosophy, ethics, politics (or bio-politics), law and ecology. To such an extent that in this day and age there is an animal turn, like previous turns that have gained the right to a trademark in the humanities and social sciences, such as the linguistic turn.

The question of animal rights rests on a notion of politics that pushes it beyond its traditional limits. To think of and defend ‘animal politics’, which in its broadest sense amounts to ecopolitics, is the task to which the Bulgarian philosopher Boyan Manchev commits himself in this article, continuing his earlier work on ‘wild freedom’.

Never before has there been such a lot of public discussion about animals, so much care and concern about how they are treated and what happens to them. Never before have animals, and not just pets, played such an important role in the human and social worlds. Today there is a very far-reaching, lively ‘animal question’ that is simultaneously galvanising philosophy, ethics, politics (or bio-politics), law and ecology. To such an extent that in this day and age there is an animal turn, like previous turns that have gained the right to a trademark in the humanities and social sciences, such as the linguistic turn.

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) and Dora Maar (1901–1997), two women and two artists. In their time, the fact that they were women severely hindered their careers as artists. For that reason, today it is impossible to look at their work without considering what restricted, governed and limited them. The retrospectives presented in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay and Centre Pompidou showcase this work, which was interwoven with the artists’ lives, where the potential and risk they represented had to be conquered. This is what the historian, researcher and curator Helena de Freitas tells us, with critical and perceptive intelligence. Her words are infused with the proud and courageous melancholy with which these artists affirmed themselves in a world that denied them.

The partial destruction of Notre-Dame by fire and Emmanuel Macron’s immediate response, promising that the cathedral would be rebuilt in record time, prompted a public discussion among experts on the forms of that reconstruction and the politics of heritage conservation (meaning also: the politicisation of heritage). This is the subject matter of the next three articles, written by Salvatore Settis, who signed an open letter to the French president demanding that the Heritage Code be respected; Carlo Pùlisci, an Italian art historian, who has published extensively on cathedrals, churches and the culture of restoration; and Pedro Levi Bismarck, an architect and researcher at the Porto University Faculty of Architecture. We are confronted with three different points of view, encompassing cultural memory and the heritage crisis (Settis), the history and culture of restoration (Pùlisci), and a political critique of conservationist logic and rhetoric (Bismarck).

The cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris probably does not need an introduction. The blaze that engulfed the church on 15 April 2019 and the ensuing debates about its reconstruction, which appeared on the front pages of much of the world’s printed press as well as on the internet and television news, thrust the monument onto centre stage, exponentially increasing its ‘celebrity status’, although perhaps not in an entirely approving way.

In one of his classes, Alexandre Alves Costa said the destruction of Cluny Abbey during the French Revolution – the paradigm of all the excesses and luxuries that characterised the Ancien Régime – represented an irreparable loss for architecture, but it was also the sign and affirmation of an irreproachable historical conquest. In fact, the history of architecture is nothing but the history of its permanent destruction, i.e. a long and endless list of burnt, plundered and imploded buildings.

All over the world, the preservation and nurture of cultural memory is becoming less and less important in terms of political priorities and public investment. Museums, monuments, archives and libraries are pitted against the vibrancy of constantly changing new technologies; and the conviction is spreading that planning for the future must be at the cost of a gradual marginalisation of the past, which is seen as a passive burden, rather than an active force, a reserve of cultural and moral energy to draw on.

These days, people everywhere are calling for a type of politics that places ethical requirements at its centre. It is time to question this stitching together of ethics and politics and the misunderstandings and consequences of this claim for the concept of politics. The response to this challenge comes, on the one hand, from Donatella Di Cesare, an Italian philosopher well-known for her books on Heidegger and the Jews (from the German philosopher’s Black Notebooks) and on the ‘philosophy of migration’, and, on the other, from Bruno Peixe Dias, a doctoral student in the area of political philosophy.

One of the most awaited returns in recent years seems to be that of ethics to politics, accompanied by the realisation that it has been missing for quite a long time. This awaiting and realisation can be found in forces and agents that are normally considered opposites. If we look at one of the largest oppositions today, we find that both the defenders of democratic liberalism and what are generally called populist movements set great store by ethics.

What relationship can there be between ethics and politics in the era that has seen the global triumph of the market and the effusions of the worldwide web, along with ecological collapse and the hyperbolic dream of the post-human? With the catastrophe created by the collision between the techno-economy and the biosphere already starting to unfold, the form of existence that survives in an immunised and closed world, with nothing outside, turns inward, prey to an overwhelming fear of anything external, dominated by an unprecedented exophobia, and unable to see beyond itself. These days it is easier to imagine becoming immortal than to envisage the end of capitalism.