In recent years, we have witnessed the emergence of a new concept − ‘post-truth’ − which has infiltrated not only the political and media scene, but also everyday lexicon. So much so that the term was proclaimed ‘word of the year’ in 2016 by the respected Oxford Dictionary, its usage having increased by 2000% compared to the previous year. Two major events triggered this proliferation: the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States.

According to the Oxford dictionary, ‘post-truth’ refers to ‘circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. Whether or not the reality of the facts informs opinion is irrelevant; what matters is the impact of the statement and the effectiveness of the ‘make believe’. It could easily be argued that this is nothing new, and that the ability of political discourse to shape public opinion has frequently – and for a very long time – been based on feelings, emotions and passions rather than on appeals to judgement and reflection.

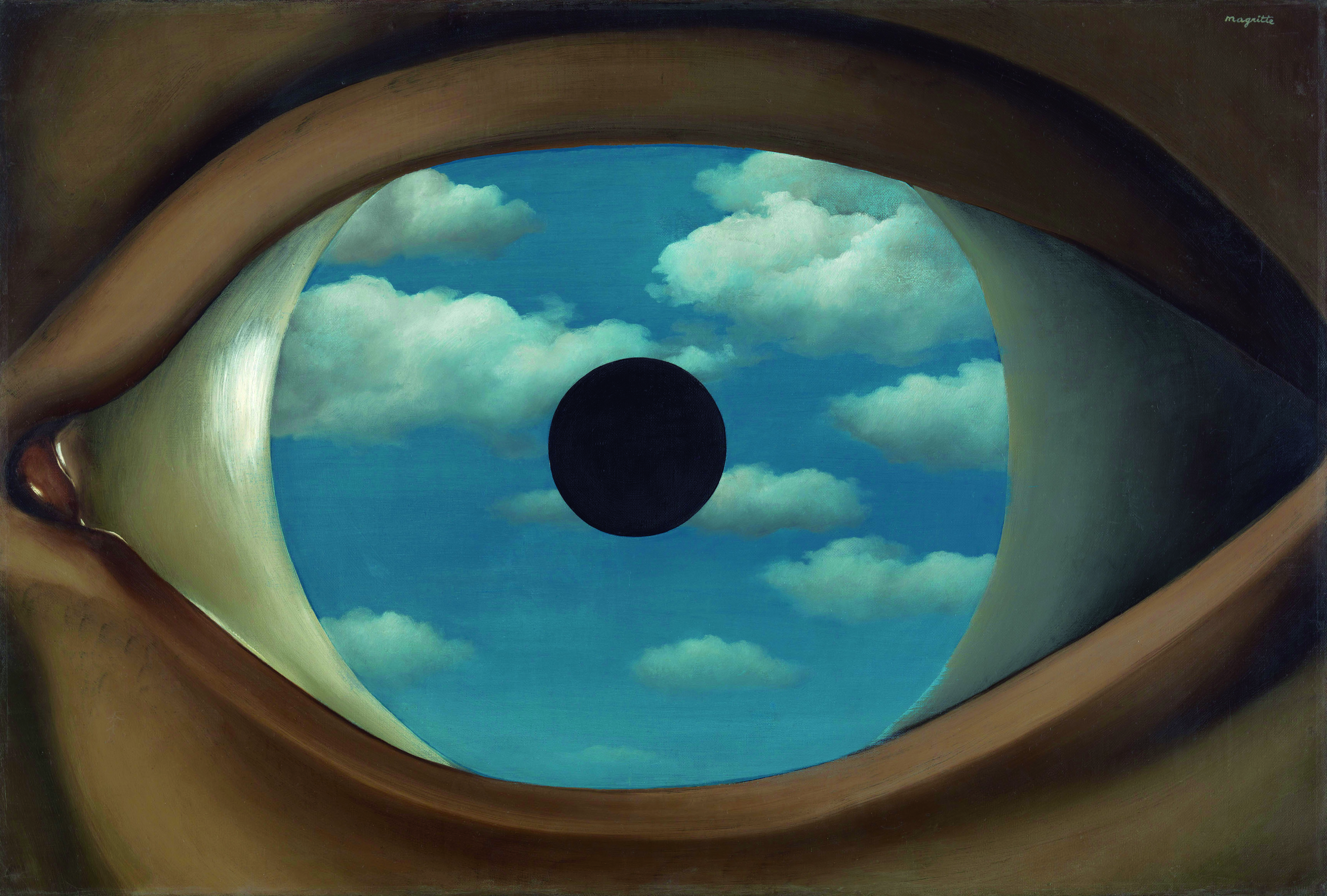

However, the dictionary adds a more interesting observation on this point: the notion to which the prefix ‘post’ is attached – namely truth – has become inessential, secondary or even irrelevant. The decisive rupture, if indeed there has been one, is that truth itself has become obsolete or irrelevant. It no longer has any effect on reality. In other words, ‘post-truth’ does not refer to the emer- gence of an era of generalised lying that has usurped one in which truth triumphed. Lies distort, truncate, conceal or deny the truth, but they do not abolish it entirely. They do not make it disappear as a normative reference. They do not eliminate the difference between truth and falsehood.

The same cannot be said of post-truth, which annihilates the very division between truth and falsehood, blurring reference points and boundaries and creating a climate of assumed indifference to truth. This phenomenon – or rather the conditions that facilitate it – has often been considered through the prism of fake news and its viral dissemination on the Internet and various social networks. No matter how hard journalists attempt to counter it with procedures for correcting and verifying information (fact-checking), the trend appears irresistible. And since 2016, the phenomenon has become even more widespread, as demonstrated by the mass dissemination of fake news by Bolsonaro during his Brazilian presidential election campaign, and the information warfare techniques used by Vladimir Putin’s regime, which involve spreading contradictory messages in all directions.

Share article