Whether we are aware of it or not, our attention is constantly lured, attracted, captivated, captured, confiscated, bought, bribed, frustrated, cheated, perverted, arrested, conquered by events, people, phenomena, apparitions, disappearances, movements, halts. When we choose to give our attention to something, we are eschewing and excluding the things to which we choose not to give our attention. This is why now we talk about an economy of attention and an ecology of attention. This is why is it said that nowadays attention is one of the rarest assets and most valuable commodities.

In a world-market full of subjects and objects, senders and recipients, producers and consumers – which moves and accelerates in a competitive vortex where everything can be bought and sold, under the rules of supply and demand, and where, thanks to communications, the distant has become near –, our attention is subjected to a constant auction.

From economy to politics, culture to society, individual to collective life, private to public space, there are devices everywhere – mobile and immobile, material and immaterial, apparent and hidden – to capture our attention. From advertising to propaganda, from traditional ads to digital ones, from social media to influencers, from communication channels to information media, we are constantly harassed in a ceaseless quest for what our attention may be worth, represent and add. Everywhere there are those who want to turn our attention into an asset that benefits them, giving us the illusion that it is an asset that benefits us.

Therefore, attention is a central question of our time and a key topic if we want to understand it. We can even talk about a phenomenology of attention. The current concept and practice of the faculty of attention, in its psychological and cognitive transformations, cultural and social changes, economic and commercial metamorphoses, offer us an expressive and symptomatic portrait of the world in which we live.

Likewise, for example, we have never talked about attention deficit so much, with its effects on education and culture. Or that the fact that many people are distancing themselves from politics, especially with the alienation of youngsters, ultimately amounts to a lack of attention and care for politics. Another example: all of those who create and disseminate culture and art know that, with the cult of the ephemeral, in a global scenario with an infinity of cultural and artistic events, they must above all draw people’s attention to what they do. Today the question of attention is mainly a question of reception-consumption.

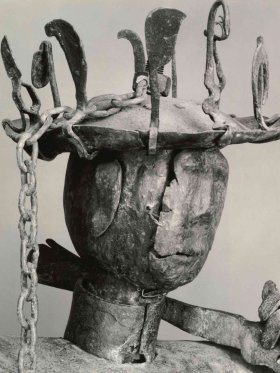

Besides this analysis of the present, the history of attention, in its theological, philosophical, literary, artistic and scientific representations and resonances, composes a collection of vast complexity and wealth.

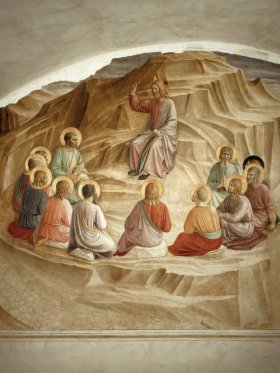

There are those who say that even without knowing its name, the economy of attention started in Classic Antiquity, when an orator would train his voice and perfect his rhetoric to gain the attention of his listeners. And this continued to be the case, from the attention of the great patrons that the Renaissance painters tried hard to gain to the attention of the inquisitors whom those suspected of heresy tried hard to evade…

But it was between 1870 and 1920 that the importance of attention became more noticeable and visible, foreshadowing and preparing its contemporary explosion. At the time, the sociologist Gabriel Tarde (1843–1904) understood perfectly well that industrialisation was causing an overproduction of commodities, where the question of attention (which advertising was starting to compete for) played a central, encouraging and mobilising role in economy and society. Since then, this importance has increased exponentially, reaching an apex in our time, as well as new features with unprecedented consequences.

By devoting the dossier of this issue to the topic of attention, Electra proposes an inquiry and reflection that are inseparable from a much-needed debate about who we are today and who we want to be tomorrow.

By reading the several essays that compose this dossier, you get an updated view of the great tree of attention: from its roots to its trunk, branches, leaves, flowers and fruit. We become more aware of what is at stake. We realise that, in recent decades, a new economy has surpassed the old and traditional ways of exchanging material and symbolic goods.

In this economy, attention constitutes the rarest thing and the most precious source of value. In our ‘Subject’, we reflect on what characterises this new economy, its active instruments and operating mechanisms, its dangers and potentialities.

From sociology to economy, from neuroscience to the new technologies, with a focus on digital technologies, from ethical philosophy to the theory of images, from architecture to performance arts, this dossier draws on the knowledge of several disciplines to establish the challenges of the new economy of attention, using various critical perspectives.

This analysis shows that today it is imperative to reflect on our economic, social and cultural life in terms of attention. And it also shows that it would be disastrous to let the productivist, consumerist, excessive and hypertelic (often anti-ecological) logic of the current financial and cognitive capitalism hegemonically reconfigure our individual and collective regimes of attention, with its transformations, demands, risks, subordinations and possibilities. The economy of attention is not just at the intersection of several contemporary disciplines and fields of knowledge and action. It places itself at the point where the paths that take us to the various choices concerning our unpredictable future meet.

In these days of tragic wars and terrible massacres, there are also other wars – those frantically vying for our attention. Representatives and supporters of both sides of each war use every means possible to make us give our full attention to their images and listen attentively to their arguments of accusation and defence. This is the time when, more than ever, the choices of our attention are moral, political and cultural choices.

Literature is an art of attention. In this issue of Electra, in the ‘Figure’ section we publish a portrait of the great Greek poet Konstantinos Cavafy and in ‘Passages’ we comment on a quote by Milan Kundera, the renowned Czech-born French novelist and essayist.

So distant in the times and places in which they lived and died, so different in the works that they wrote, so remote in their life experiences, so diverse in their cultural conceptions, so distinct in their sensitivities and interests, there is however a bond uniting them: the attention given to the link between the past and the present, the presence of History in their individual experiences and in the books that they wrote. For them, History and the past are like background cosmic noise. They shape the world of each present, and condition individual freedom and the possibilities of living, thinking, suffering, creating, deciding, and loving freely. This feeling of a past that is present is experienced by Cavafy with melancholic fervour and by Kundera with enraged passion.

Share article