'One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.'

Oscar Wilde

The writer, psychoanalyst and curator Sinziana Ravini in this article describes and analyses an artistic attitude that found its perfect manifestation in the dandyism of the second half of the 19th century and then in the historical avant-gardes of the early 20th century. This attitude consisted in aestheticising life and making it a work of art, as did Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde to the highest degree.

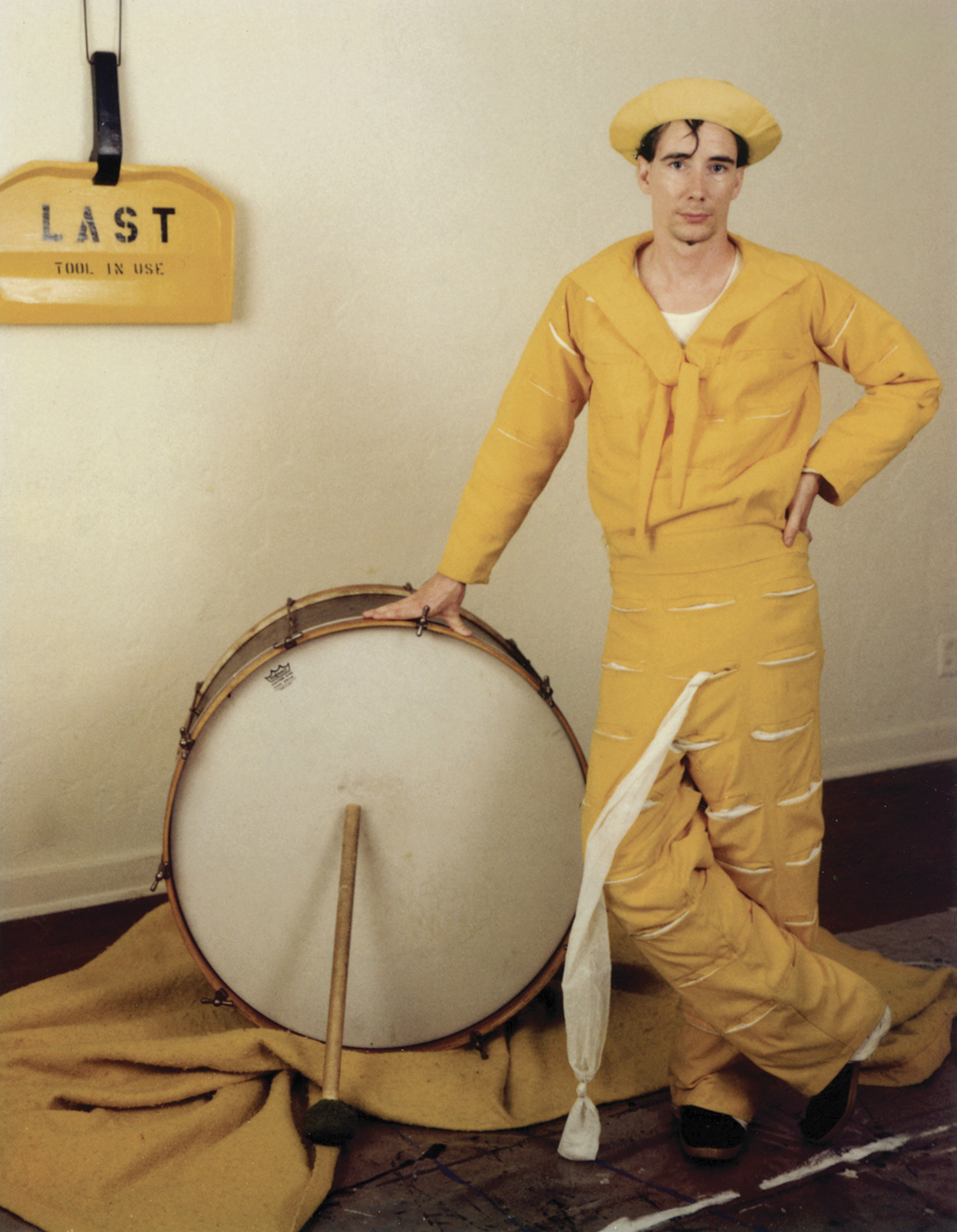

Mike Kelley, The Banana Man, 1983 © Photo: Jim McHugh / Mike Kelley Foundation, Los Angeles

In this age of ‘artist capitalism,’1 of which the aestheticisation of life is a permanent feature, it has become commonplace to turn one’s life into a work of art, as the artists of the modern avant-garde did. And yet we seem to be worlds apart from these dandies from another era, who knew better than anyone else how to go against the grain of their times. What is the aestheticisation of life all about? And what is the origin of today’s infatuation with the blurring of the boundaries between private and public life among those who govern us politically or artistically? Is the exhibition of life a relic of the avant-gardes? Or rather the result of a more archaic economy of pleasure?

I’ve always been fascinated by those who sought to transform their lives into works of art while resisting the triumph of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie, in cities crushed by the profit motive and the exploitation of human beings and natural resources. ‘There exist only three respectable beings: the priest, the warrior, the poet. To know, to kill, and to create,’ says Baudelaire in Mon coeur mis à nu [My heart laid bare]. Despite Brummell’s claim that, after Napoleon, one could no longer be a soldier,2 the dandy, like the poets of the avant-garde, was a warrior who waged war on reality.

"Whether a real person or a character in a novel, the dandy is always someone who invents himself."

The avant-garde emerged as early as 1830 out of a desire to deconstruct the false autonomy of art for art’s sake, as seen in Théophile Gautier’s preface to Mademoiselle Maupin, for example. Gautier, who initially wanted to separate art from life in order to get closer to both, became the first poet to deliver a programme of disengaged art that was as aesthetic as it was comic. His antagonists? The ‘dragons of virtue’: journalists turned priests, who, without our vices, would be reduced to begging. For Gautier, the only purpose of life is entertainment. God wanted it that way, he reassures us, because it was he who created perfumes, beautiful flowers, good wine, greyhounds and angora cats; he who allows us to drink without being thirsty and to make love in all seasons, actions that distinguish us from the brute much more than reading newspapers or writing charters. This joie de vivre is often accompanied by a dolce far niente. ‘A dandy does nothing,’ said Baudelaire, and yet Baudelaire and his ilk would never have secured a place in history had they not been consumed by the demon of work.

Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie, Jean-Luc Godard, 1962

The invention of the self

Whether a real person or a character in a novel, the dandy is always someone who invents himself. While Romantic heroes saw themselves as being haunted by the Devil, modern heroes like Gautier’s ‘Dandy Beelzebub’ in Albertus, Baudelaire’s Generous Gambler, or the protagonist of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s disturbing Le Convive des dernières fêtes [The eleventh-hour guest], seem to be at one with their accursed side. In Mon coeur mis à nu, Baudelaire writes: ‘There are in every man, always, two simultaneous allegiances, one to God, the other to Satan. Invocation of God, or Spirituality, is a desire to climb higher; that of Satan, or animality, is delight in descent,’ as if he had just read Freud’s theories on the life drive and the death drive.

Perpetually in search of aristocratic elegance, the dandy prefers the malice of small gestures, a face masked by invulnerability, biting irony on the lips, a wounding smile, a well-placed bon mot. He plays, but does not open up; he is a ‘dilettante who clenches his teeth.’3 What crushes the dandy is boredom. In one of his letters, Flaubert evokes a deep sadness that comes from nothing but the very substance of existence: ‘When I was very young, I had a complete premonition of life. It was like the stench of cooking escaping through a basement window. You don’t need to have tasted it to know that it’s enough to make you vomit.’ It was against this vomit-inducing existence that the accursed poets rebelled, seeking to manipulate reality as if it were modelling clay: ‘You gave me your mud and I have turned it to gold,’ declared Baudelaire in Les fleurs du mal.

When Baudelaire rages against existence, iron sends him back to the mud of hell, but hell is also on the side of iron, as if there were no way out of this infernal circle. ‘Hell is other people,’ said Sartre, who was so fond of Baudelaire. For Baudelaire, hell was also women: ‘Woman is the opposite of the Dandy. / Therefore she must inspire horror. / Woman is hungry and she wants to eat. / Thirsty and she wants to drink. / She is rutting and she wants to be fucked. / Beautiful merit! / Woman is natural, that is abominable.’ Not for nothing did women emerge in this period as the very incarnation of evil in the myth of the ‘femme fatale.’ Dandies also had trouble with nature. ‘I detest the countryside, with all its trees, earth, and grass! How does it make me feel? It’s all very picturesque, but boring as hell,’ wrote Gautier in the preface to Jeunes-France. Criticism of society therefore extends to the whole of existence, and it could even be said that making one’s life a work of art indirectly implies suppressing it.

[...]

Share article